PANW Editor's Note: The following two articles were originally written and publsihed in 1998 and 2002 respectively. The first article was written in commemoration of the anniversary of the death of the late Pan-African leader, Dr. Kwame Nkrumah. Only minor revisions were made in this article for the purposes of historical clarification. Otherwise it remains in the same form as previously published in 1998. The second article was written in the aftermath of the 2002 national presidential elections in Zimbabwe during which time the governments of the United States and the UK sought to influence the poll to overthrow the leadership of President Robert Mugabe and the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union, Patriot Front (ZANU-PF). It is being published in its same form as was done in 2002.

---------------------------------------

By Abayomi Azikiwe, Editor

This article was previously published as a Pan-African News Wire, Weekly Dispatch on April 27, 1998

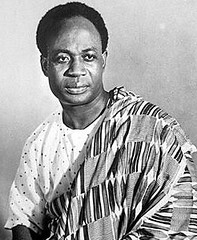

A Tribute To Kwame Nkrumah On The 34th Anniversary of His Death

Editorial Review, April 27,(PANW)--Thirty-four years ago today in 1972, Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, the founder and leader of the African independence movement and the foremost advocate of Pan-Africanism during his time, died in Bucharest, Romania after a long bout with cancer. Nkrumah was the first head of state of an independent post-colonial nation in Africa south of the sahara, after he led the nation of Ghana to its national liberation under the direction of the Convention Peoples Party in 1957.

Educated at the Historically Black College ofLincoln University in Pennsylvania, Nkrumah became involved in the Pan-African movement in the United States during the 1930s and 1940s as a leading member of the African Students Association (ASA), the Council on African Affairs (CAA) as well as other organizations. After leaving the United States at the conclusion of World War II in 1945, he played a leading role in the convening of the historic Fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester, England-a gathering which is credited with laying the foundation for the mass struggles for independence during the 1940s and 1950s.

It was during his stay in England between 1945-47, that he collaborated with George Padmore of Trinidad, a veteran activist in the international communist movement and a journalist who wrote extensively on African affairs. Nkrumah was offered a position with the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) as an organizer in late 1947 and made a critical decision to return to the Gold Coast (later known as Ghana) to assist in the anti-colonial struggle that was intensifying in the aftermath of World War II.

After being imprisoned with other leaders of the UGCC for supposedly inciting unrest among WWII veterans, workers and farmers in the colony, he gained widespread popularity among the people who responded enthusiastically to his militant and fiery approach to the burgeoining anti -imperialist movement. After forming the Committee on Youth Organization (CYO) which became the best organized segment of the UGCC, Nkrumah was later isolated from the top leadership of the Convention, who objected to his demands for immediate political independence for the Gold Coast.

On June 12, 1949, Nkrumah and the CYO formed the Convention Peoples Party in Accra at a mass gathering of tens of thousands of people, who were prepared to launch a mass struggle for the abolition of British colonial rule in the Gold Coast. During this same period, Nkrumah formed links with other anti-colonial and Pan-African organizations that were operating in the other colonies of west Africa. When the CPP called for a Positive Action Campaign in early 1950, leading to massive strikes and rebellion throughout the colony, he was imprisoned by the colonial authorities for sedition. However, the executive members of the CPP continued to press for the total independence of the colony, eventually creating the conditions for a popular election in 1951, that the CPP won overwhelmingly. In February of 1951, Nkrumah was released from prison in Ghana and appointed Leader of Government Business in a transitional arrangement that eventually led to the independence of Ghana on March 6, 1957.

At the independence gathering on March 6, Nkrumah declared that the independence of Ghana was meaningless unless it was directly linked with the total liberation of the continent. This statement made by Prime Minister Nkrumah served as the cornerstone of Ghanaian foreign policy during his tenure as leader of the country. George Padmore became the official advisor on African affairs and was placed in charge of the Bureau of African Affairs, whose task it was to assist other national liberation movements on the continent in their efforts to win political independence.

In April of 1958, the First Conference of Independent African States was convened, with eight nation-states as participants. This gathering broke down the colonially imposed divisions between Africa north and south of the sahara. Later that same year in December, the first All-African Peoples Conference was held in Accra, which brought together 62 national liberation movements from all over the continent as well as representation from Africans in the United States. It was at this conference in December of 1958, that Patrice Lumumba of Congo became an internationally recognized leader of the anti-colonial struggle in that Belgian colony.

Challenges of the National Independence Movement

By 1960, the independence movement had gained tremendous influence throughout Africa, resulting in the emergence of many new nation-states on the continent. That same year, Ghana became a republic and adopted its own constitution making Nkrumah the president of the government. However, there arose fissures within the leadership of the CPP over which direction the new state would take in regard to its economic and social policies.

Many of Nkrumah's colleagues who had been instrumental in the struggle for independence, were not committed to his long term goals of Pan-Africanism and Socialism. Consequently, many of the programmatic initiatives launched by the CPP government were stifled by the class aspirations of many of the state and party officials who were non-committal in regard to a total

revolutionary transformation of Ghanaian society and the African continent as a whole. By September of 1961, massive labor unrest occured throughout the country while Nkrumah was travelling in Eastern Europe, which was then allied with the Soviet Union.

In the aftermath of the 1961 crisis, massive purges took place within the CPP against those who were considered to the right of the new government policies related to the adoption of scientific socialism inside the country. Later in August of 1962, an assassination attempt was carried out

against Nkrumah in the north of the country, where he was nearly killed by a bomb. As a result of this incident,a new round of purges took place where many of those considered as the left wing of the CPP, such as vice-chairman of the ruling party, Tawio Adamafio, were sacked and later arrested and charged with being co-conspirators in the assassination attempt against Nkrumah. After 1962, the leadership of the CPP became more focused around Nkrumah as a personality while the government moved more towards the adoption of a one- party state model of political control. These developments were taking place in conjunction with other activities launched by opposition parties, whose strength had been curtailed by the Preventive Detention Act of 1958, that was designed to halt other plots aimed at assassination and destabilization of the new state in the aftermath of independence.

By 1964, the First Republic of Ghana had held an election that mandated the adoption of the one-party state form of government. During this period, the CPP was attempting to restructure the economy of the country from its dependence on trade and investment with the capitalist world. This proved to be a formidable task due to the legacy of colonialism in the country and the relative weakness of the Soviet Bloc and China in regard to their ability to provide economic assistance to newly independent African states. Although the realization of an United States

of Africa was the principle foreign policy objective of the CPP government, the majority of African states during this period were not willing to lessen their ties to the former colonial powers in lieu of greater linkages with the progressive states on the continent. Nkrumah in

1963 identified neo-colonialism as the major impediment to the genuine liberation of Africa. At the founding meeting of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, he released his book entitled, "Africa Must Unite", which provided a proposal for the adoption

of a continental union government as the only means of countering the development of a new form colonialism on the continent.

At the OAU conference in Egypt during July of 1964, Nkrumah pleaded for the adoption of an United States of Africa by the heads of state. This proposal was not accepted despite the apparent problems associated with the legacy of colonialism on the continent. The Congo crisis and the economic stagnation of many of the newly independent states illustrated that the these nations were not viable as economic and political entities.

At the 1965 OAU Summit held in Accra, many of the head of states from other nations did not attend because of their opposition to the foreign policy of the CPP government. At this conference in late 1965, Nkrumah issued his book entitled, "Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of

Imperialism", which condemned the United States as the principle imperialist power behind the new form of hegemonic rule which was designed to maintain western control over the newly independent states in Africa and throughout the so-called developing world. This book so

infuriated the American government that G.M. Williams, the United States Undersecretary of State for African Affairs wrote a memorandum of protest to Ghana embassy in Washington, D.C. saying that Nkrumah was working in contravention to the interest of the American government in Africa.

Just four months after the release of this book on Neo-Colonialism, Nkrumah was overthrown by a coup d'etat led by lower level military officers and police in Ghana. This coup was backed by the American government and the imperialist world in general, who percieved Nkrumah's policies as a threat to the economic and political interests of the western powers. Nkrumah was out of the country at the time of the coup, enroute to North Vietnam on a mission to bring about a peace settlement in the United States war against the people of South-east Asia. During a stop

over in China, Nkrumah was informed by the governmental officials there that a military and police coup had taken place inside of Ghana. Aborting his mission to Vietnam, he returned to Africa via the Soviet Union and Egypt,where he eventually settled in Guinea-Conakry. Nkrumah remained in Guinea until he was flown to Romania to undergo treatment for cancer in 1971. During this period after the coup (1966-1971) he continued to write on the history of Africa and the revolutionary movement for Pan-Africanism and world socialism.

The Contributions of Kwame Nkrumah

Despite the coup against Nkrumah on February 24, 1966 in Ghana, his legacy in Africa and throughout the African world continues. His views on the necessity of coordinated guerrilla warfare to liberate Africa was realized in the sub-continent during the 1970s and 1980s, when the settler-colonial regimes of Rhodesia and eventually South Africa were defeated. The role of Cuba in the liberation and security of Angola was clearly in line with the notions advocated by Nkrumah, which upheld the view that until settler colonialism was destroyed, the entire continent of Africa would not be secure.

Even though the realization of a United States of Africa is still far away, this issue continues to be discussed broadly on the continent and in the Diaspora. In Ghana, Nkrumah's legacy was utilized in both a positive and negative manner by the successive regimes that took power after his departure. These regimes are compelled to use his image and legacy, despite their refusal to adopt the CPP program in its totality.

In the United States and throughout the Diaspora, a greater identification with Africa has occured over the last thirty years. The African community in America and the Caribbean played an instrumental role in the solidarity struggle with the national liberation movements in Southern Africa during the 1980s and 1990s.

Nkrumah's views on the necessity of African unity have been prophetic in light of the continuing underdevelopment of the continent and the phenomena of domestic neo-colonialism in the United States and the Caribbean. Consequently, the legacy of Nkrumah is still relevant to the present day struggle of African peoples around the world.

A greater understanding of his ideas and activities can only benefit the present efforts to create an African world that is genuinely independent and self-determined.

===========================================================================

Articles published by the Pan-African News Wire may be freely ciruculated for non-profit educational and research purposes. We request that the original source of these articles be cited when reproduced. Distribution for profit is prohibited without the expressed consent of the Pan-African News Wire.

===========================================================================

No comments:

Post a Comment