Women's Movement

Now is the time, our age of hope

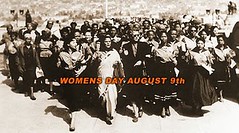

Fifty years ago, on 9 August 1956, the women of South Africa were galvanised into that great tide that saw a male racist chauvinist flee in front of their anger. We owe it to them to recognise, learn from and pay tribute to their historic actions that laid the foundation for the democracy we have achieved and the strides we have made on our determined march to gender equality.

However the best tribute we can pay to these heroines and the heroes is to defend the gains made and also in action, to change the lives of those who have yet to taste this freedom in real terms, the majority of whom are the black, poor, rural and working class women existing on the periphery of society. All of us should unite with them in action to make sure that in reality "today is better than yesterday and tomorrow will be better than today".

The people and the government of South Africa have put in place many policies, laws and institutions to ensure that women not only regain their dignity but are "mistresses" of their own destinies. Papers have been written in praise of the achievements made in South Africa and in particular in the inclusion of women in decision-making spheres. Tempting as it is to analyse the gains and the gaps, this contribution is directed only at the current debate on the 'formation' of a 'South African women's movement'.

The story of 'forming' a Women's Movement in the current period dates back to the Malibongwe Conference in Amsterdam in 1989. In the glorious, long and arduous road to freedom, there have always been women's movements. If by a 'women's movement' we mean all women who recognise the need to mobilise and organise themselves at any level and engage in any form of struggle to better their lot, or fight against any form of discrimination against women, or engage in any form of struggle for the achievement of women's emancipation and gender equality, then there has been not one women's movement, but many.

The debate about forming a woman's movement should therefore not be taken to mean that there has never been one or that none currently exists. The debate should in fact be informed by these, their experiences, victories and challenges.

The launch of the South African Women's Movement should be used to dialogue and strategise for further onslaughts against patriarchy, that abominable system, ideology and practice of domination of women by men that permeates all spheres of our lives.

Democracy is crucial for, and has contributed to, the road to gender equality in our country, including the improvement of the status and quality of life of women. It has also very importantly created the opportunity and a healthy environment for furthering the gender struggles. However it is not sufficient for dislodging patriarchy. We still have to do much more for the complete eradication and transformation of all power relations in society, across which runs the gender inequality thread. The whole society has to be mobilised into a strong and vibrant movement for transformation, at the centre of which should be a women's movement driven by women, particularly the most marginalised poor, black, rural and working class women.

Patriarchy cannot be eradicated only by government, or one group or organisation. It needs all forces within society. Particularly because it coexists with, and survives even under, the most progressive political systems; because it is articulated in many diverse subtle and hidden or open and crude forms; because it is explained away in many logical-sounding ways ranging from the natural, biological to religious and cultural arguments; because one of its strongest bases is the family, the home, and among loved ones; and because it is the most complex and entrenched system embedded in, and permeating through, all spheres of life, it needs all forms of struggle - persuasion, contestation, compromise, pressure and confrontation. The struggle against patriarchy is a "struggle within the struggle". The different forms and levels of engagement, organised or not, formal or otherwise, constitute the women's movements.

Women's struggles take different forms and occur in different localities determined by diverse interests and needs. Some women, especially poor and black women, are mobilised in their communities and localities on needs that are so basic they are taken for granted (like access to clean water). They thus struggle for elementary rights. Their needs are classified by some scholars as the practical gender needs (PGNs). Significantly, these women and their organisations do not link their situation to that of patriarchy. They may even accept the biological, religious or cultural explanations of their place and role in society.

If women's struggles and organisations were to be presented in a continuum, the basic needs group, sometimes called the popular women's movement, would be at the one end. Towards the other end would be the strategic gender needs groups (SGNs). These include, but are not limited to, feminists (of many kinds) mainly concerned with the complete eradication of unequal power relations between men and women. Some of these look down on the practical gender needs and struggles maintaining that these wittingly or unwittingly reinforce the socially defined but not natural role of women as being in the domestic sphere. Of significance with these is that they have many different and diverse theories to explain the root of and path to the eradication of patriarchy and how to change it.

At the other end of the continuum would be what some of us call the transformative group that is committed to a transformative agenda. These acknowledge and are directly and indirectly involved in the whole range of the struggles, from the practical through to the strategic needs, seeing each as a necessary building block for women's emancipation, gender equality and a competently transformed society that has eradicated all forms of inequality, oppression and discrimination. They use different strategies, tactics and participate in all kinds of organisations and struggles. They fight for access to water and access to decision-making bodies, use power to transform power and its instruments, and transform society and social relations.

There are no borders between these groups and struggles. There is mobility, support and solidarity, and sometimes overlaps, among them. All of these strands have gone through highs and lows at different times and for different reasons.

One of the lessons that will have to be learnt is the challenge of politics of access, inclusion and participation. When some of us moved into the state and its machinery we had to shift the sites to other battles. While this was very good, the unintended consequence was a temporary demobilisation and expectations of delivery from a state that has so many women. In some cases the politics and advantages of access and inclusion prevailed with many acting as if the mere act of inclusion was transformation, and not a step towards transformation.

As we prepare for the formation of this movement, the lessons have to be brought to the fore for us to emerge stronger. This becomes critical as it determines how in this complex epoch we unite in action for the bigger goal of equal gender relations.

The strength of any movement lies in its ability to link with others. The women's movement should therefore include, but not be limited to, these networks and organisations. It should be the much-needed coordination, cooperation and collaboration point for solidarity and united action.

One of the weaknesses we have had as the Alliance has been the poverty of gender theory. This makes us lurch from side to side as a rudderless ship on the seas of gender engagement. Some kind of theory emanating from our and other experiences would help us to have markers and pointers in our struggle. A women's movement does not necessarily evolve around a theory, but it needs a basic reference point beyond the slogans of engendering, mainstreaming, integrating gender, etc. South Africa as a whole is poorer for the limitation of the intellectual debate especially on these matters. Many women in South Africa have the practice, but that is not sufficient for the transformation agenda. Practice and experience needs to be continuously fortified by theory, while in turn enriching theory.

These are the pieces of the jigsaw that have to be put together to form the tapestry of one women's blanket - with identifiable and distinct colours and yet forming part of the whole. The thread knitting us together would be our action plan, unity in action and commitment to completely overthrow patriarchy and all its manifestations. We are ready, able and willing. Now is the time, our age of hope.

** Thenjiwe Mtintso is a member of the ANC National Executive Committee. This is an edited version of an article that appears in the forthcoming edition of the ANC political discussion journal, Umrabulo.

BLOEMFONTEIN 6 August 2006 Sapa

WOMEN SHOULD ACT FOR EMANCIPATION: MLAMBO-NGCUKA

Full emancipation of women, like the struggle against passes and apartheid, requires them to take actions that are as significant as that of marching to the Union Buildings, Deputy President Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka said on Sunday.

She was speaking at a conference to launch the Progressive

Women's Movement of South Africa in Bloemfontein.

"We have to organise around issues that matter to the majority

of women".

The women who made the contribution to fight for freedom could

never have done it without devotion to organisation, in particular at grassroots level.

"To get 20,000 Women marching to present over 100,000 petitions, without present day connectivity, means this was hard-earned organising capacity, which we have lost, " said Mlambo-Ngcuka.

Citing some of the challenges that women faced, she put

education at the top of the list.

"Education for women therefore is a must. It is needed to change

the position of women dramatically".

She said women still had to fight to be CEOs, to be on boards

and in executive management.

"The role and investment that has to be made in education must

mean we decrease teenage pregnancy and growing levels of dependency on the State."

Mlambo-Ngcuka urged older women, not only those in prominent

positions, to educate and nurture younger women to allow them to lead and contribute.

"The discussions we will be having here must lead us to commit

to a united purpose, all of us can and must aim to make a

difference."

Economic liberation was still a missing piece.

BLOEMFONTEIN 6 August 2006 Sapa

WOMEN'S MOVEMENT LAUNCHED IN BLOEMFONTEIN

Hundreds of women gathered in Bloemfontein on Sunday for a

conference to launch a new national movement, the Progressive

Women's Movement of South Africa (PWMSA).

"The PWMSA is the result of deliberation among the country's

women that without a women's movement the gains made so far for women's rights could not be guaranteed," said movement convener Mavivi Myakayaka Manzini.

"[Nor] will we be able to carry out the objectives of

eradicating gender equality in our society without such a

movement."

Myakayaka Manzini said the new movement would not replace other women's organisations.

"A united and powerful voice of women on many issues affecting

us, have not been loudly heard," she said.

The women attending the two day founding conference represent

various women's organisations from all nine provinces in the

country.

Also present were the Deputy President of South Africa, Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka; Deputy-President of Zimbabwe, Joyce Mujuru; the Mozambican Prime Minister, Luisa Dias Diogo; and several of South Africa's women ministers, deputy ministers, ambassadors and premiers.

"We hope to emerge from this conference with a founding document which would clearly say what we are standing for and how we would operate as a movement," Myakayaka Manzini said.

The movement would build on the point of view that women's

rights were also human rights and that these rights were

interrelated.

"It would also be non-party politicaland non-partisan," she

said.

Myakayaka Manzini paid tribute to the South African Government

for what it had done for women's rights and its commitment to

improve gender equality since former president Nelson Mandela came into power.

"Now it is time to see that those commitments are truly

implemented. We believe that without a viable and strong women's movement these achievements can be eroded."

Also addressing the women on Sunday, Foreign Minister Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, said there were still many challenges facing woman.

These included more representation of women in government

structures. "We should (also) admit that in the sharing and

distribution of wealth we have not done so well, so that is a big challenge."

Dlamini-Zuma, co-convener of the conference, said the forum

should also discuss how the movement could bring younger women into the mainstream of women's movements.

She stressed that the movement should recognise the importance

of alliances with men. "We must also forge alliances with men if we are to build a strong progressive women's movement for social transformation.

"We have to forge strategic alliances with those men who

understand that there is no justice for anyone if there is no

justice for women."

Dlamini-Zuma said no country could boast being free if its women were not free.

The challenges still facing women, as discussed by the

conference, would be incorporated into a memorandum that would be handed over to the Presidency during a march re-enacting the Women's March of 1956.

The national Women's March on August 9 would be to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the anti-pass protests held at the Union Buildings in 1956.

No comments:

Post a Comment