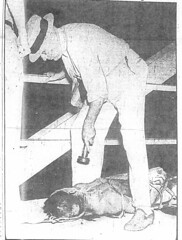

Tipton County, Tennessee Sheriff W.J. Vaughn Flashes Light on Lynching Victim Albert Gooden During Early Morning Hours of August 17, 1937

Originally uploaded by panafnewswire.

By Abayomi Azikiwe

After the peak period of the 1890s, most studies of lynchings indicate that there was a decline in mob violence against African-Americans that continued through the years leading up to World War I. After the War, race riots erupted throughout the United States at a level of intensity that would exceed the events of 1906-1908, when large scale attacks occured on the African-American community in Atlanta, Georgia and Springfield, Illinois. Another perceived decline in the rate of lynchings occured during the 1920s, only to see a marked upsurge after the onslaught of the Great Depression during the 1930s. Despite the quantitative reversals in the incidences of public white mob violence designed to maim and murder African-Americans, the atmosphere of racial dominance remained staunchly in force throughout the 1930s. With the improvement of the United States economy during the previous years of the 1920s, African-Americans continued their mass migration out of the rural and urban areas of the South to the norther industrial cities. These economic and migratory factors may have served to temper the overt acts of racial hatred in the southern states during this period.

Legal efforts aimed at the curtailing or abolishment of lynching were never successful in the United States. Although Ida B. Wells-Barnett's most significant contribution was raising the national and international public consciousness in regard to the immorality and hypocrisy of the white rational for mob violence, no national legislation was ever passed aimed at creating a federal law against lynching. Proposed laws would have had officials and criminals responsible when lynchings took place in their respective counties. It was the broad potential for prosecution in federal courts that brought about the tremendous opposition to these proposed legislative efforts.

After attempts by the Populist Party to place anti-lynching legislation on the national agenda in the 1890s, the introduction of a bill did not occur in Congress until 1922. This federal anti-lynching bill was drafted and introduced by Representative Leonidas C. Dyer of Missouri. Even though it passed the House of Representatives by a margin of 231-119, the Senate under John K. Shields of Tennessee, used the filibuster to prevent the legislation from being approved. It was defeated again in 1924 as a result of an alliance between southern legislators and their western counterparts.

With another upsurge of lynchings beginning in 1930, when there were 20 officially reported extra-legal murders of African-Americans by white mobs, Senator Robert L. Wagner of New York and Edward P. Costigan of Colorado, introduced another anti-lynching bill in Congress during early 1934. This bill also met defeat when a coalition of southern and other conservative legislators opposed its passage. When a series of brutal lynchings occured during the renewed economic recession of 1937, a new bill was re-introduced by Senator Wagner and Fredrick Van Nuys of Indiana. The bill did reach the Senate floor, but was tabled prior to a Congressional recess for fear of defeat by filibustering southern Senators. It was during the Congressional recess of 1937 that the first case study cited here occured in Tipton County, Tennessee, located in the agricultural rich southwest region of the state.

The Lynching of Albert Gooden in Tipton County, Tennessee (1937)

Tipton County, Tennessee in 1937 was a "black belt" area where the largely rural African-American community constituted nearly half of the population. With the smaller percentage of African-Americans living in the towns of Covington, Mason and Brighton, the majority of this population resided on the farms and plantations controlled by descendants of white planters, many of whom had settled in the County during the initial cotton boom of the middle 19th century. A large number of poor landless whites also lived in the County and were in constant competition with African-Americans during the Depression years for limited economic resources. Developments during the early years of the 20th century set the pattern for a greater desperation on the part of small white farmers in the South, many of whom did not own land.

According to the findings of Tolnay and Beck: "between 1900 and 1930, the number of white tenant farmers in the South increased by 61 percent, while the number of black tenants increased twenty-seven percent. As a result, despite their membership in the dominating caste, more rural whites began to sink to the same disadvantaged economic position as blacks. For the first time sizable numbers of southern white farmers found themselves in direct economic competition with southern black farmers."

When a shooting incident erupted on July 18, 1937 in Mason, Tennessee resulting in the deaths of Jack Bolton, an African-American male 24 years of age, and Night Marshall Chester Doyle, a Deputy Sheriff in Tipton County, the stage was set for one of the most representative acts of racial violence during the period. Press reports indicated that Marshall Doyle was conducting a raid on an illegal gambling establishment operated by Albert Gooden, 25. As a result of a dispute over alleged disrespect by law-enforcement officials towards an African-American woman present during the raid, a conflict ensued where shots were fired on both sides. The deaths of Bolton and Doyle created a chain reaction of events beginning with the arrest of Albert Gooden for the charge of murdering the white Deputy Sheriff, Chester Doyle.

After Gooden was taken into custody in Covington, it was reported that "ten carloads of white men drove to the...jail" with the expressed intention of lynching the suspect in Doyle's death. Immediately the County Sheriff, Will J. Vaughn, was credited by the press with swiftly removing Gooden from the jail, transporting him 40 miles to a Memphis jail for his security pending the beginning of the trial in Tipton County in August. According to Vaughn, Gooden was taken to Memphis for "safekeeping."

On the night of August 16, nearly one month after the initial killing of Deputy Sheriff Chester Doyle, Vaughn was transporting Gooden from Memphis to Covington in order to begin the murder trial. During the drive to Covington, the Sheriff claimed that he was forced off the road by a black sedan after crossing the Tipton County border line. This sedan, according to Vaughn, contained six masked white men that he did not recognize, who demanded that he hand over Gooden to them. Vaughn also contended that he was overpowered by five of the masked men who then captured Gooden and forced him into their vehicle and sped away. This story was viewed skeptically by the African-American press because of the lack of information related to the identities of the alleged kidnappers. In addition, the puported masked men making up the mob, left Sheriff Vaughn and businessman John Winford with the car keys to their vehicle after they allegedly left with Gooden.

According to Vaughn, no one else knew about his trip to Memphis and the intended route driven back to Covington on the night of August 16. His passenger and friend, John Winford, a local businessman, was supposedly unaware of the purpose or the specific destiny of the trip to Memphis. However, it was never adequately explained to the Tipton County Grand Jury impaneled by R.B. Baptist to investigate the disappearance and murder of Gooden, the reason why the perpetrators knew exactly where to stop the vehicle driven by the Sheriff. Six hours after the alleged abduction of Gooden, his corpse was supposedly discovered by Vaughn and his deputies nine miles from the area where he was "kidnapped" by the six hooded white men.

The Atlanta Daily World of August 18, 1937 reported on the murder by writing the following:

"The body lay in grotesque quiet beneath the span of a country road bridge. The muddy waters of Beaver Creek, a meandering drainage ditch, lapsed over Gooden's head while the remainder of his bloody mud-soaked body lay on the bank."

The article goes on to describe the murder scene:

"His body was punctured with more than 30 bullets. Around his neck looped twice-- was a worn plow rope that had broken when the abductors shot their victim and then attempted to hang the body from the bridge."

In the Covington Leader of August 19, 1937, an article states that:

"The negro was lynched, presumably a short while after his capture, at an iron bridge over the Beaver Bottom drainage canal on a dirt road between Wright's and Gainsville. The body, however, was not discovered until about 3 o'clock Tuesday morning, when Chief Deputy V.W. Pickens and Special Officer J.T. Scott, both of Covington, were searching the area and found the bridge floor covered with cartridges. They also found lying on the bridge the sheriff's pistol, which was taken from him by members of the mob."

The article in the Covington Leader continues by saying that:

"When found the dead negro was still hand-cuffed and was lying on the edge of the canal, his head in the water. A piece of frayed rope, which had either been shot in two or had broken when he was thrown or pushed from the bridge, was still tied about his neck. The other part of the rope was still tied to the bridge. The negro had been riddled with bullets, several dozen bullet wounds being found. The head had been almost severed, apparantly from a charge of buckshot. The bottom of the canal is about 15 feet from the top of the bridge railing, and it could not be determined whether his neck was broken before the rope parted or whether he died of pistol and gunshot wounds.... The body was brought here by a colored mortician, the sheriff later turning the dead negro over to his brother, also a mortician."

In an account published in the Atlanta Daily World on August 25, 1937, which describes the reaction of Gooden's family to the tragedy, journalist Nat D. Williams of Memphis stated that the body was found "late Monday night, August 16, close to the Mount Pleasant Baptist Church near the Brighton community, between Mason and Covington, two small towns in Tipton County in rural West Tennessee. His mother wouldn't even look at his remains. She couldn't stand it. Southern tradition was asking too much--even of a mother. His father, built of a little sterner stuff, and retaining a bit more composure, made the arrangements. His brother, operator of a burial association, looked after the materials and things. He even took one of his hearses and went to Covington early Tuesday morning, after three 'laws' (the colored folk call officers that in Tipton County), had awakened him and his wife about six o'clock in the morning and told them that they could 'go over and get Albert now, or leave him with H.L. Porter,' the colored undertaker in Covington who first picked up the lynch victim's body off the bridge."

Williams then remarks that: "(Funny thing about Porter...he got lost on his way to get the body...he did not give any reason.) Porter and other leading colored folk in Covington and nearby communities won't have much to say about the lynching pro or con. They take the attitude of letting the white folk do all the worrying."

Despite the convening of a grand jury and the hearing of testimony by a least ten persons, including law enforcement personnel in the County, no indictments were served in the murder. With national attention focused on the epidemic of lynching during 1937, state officials and the white press in Tennessee roundly condemned the lynching. Circuit Court Judge R.B. Baptist, the convenor of the grand jury which was charged with investigating the lynching, stated that the murder of Gooden was "one of the most horrible and disgraceful crimes of Tipton County...and it is the duty of the grand jury to make not a perfunctory-- but a full, complete and searching investigation and go to the bottom of this thing". Press accounts of the lynching claimed that it was the first since the Civil War in the County. However, at least one other lynching occured in November of 1894, when Needham Smith was shot to death after being falsely accused of the rape of a Caucasian woman.

Despite strong words from the Judge, the white press and the Governor, who offered a $5,000 reward for the capture of the lynchers, the murderers of Albert Gooden were never brought to trial. Sheriff W.J. Vaughn maintained that he did not know the identities of the masked men who had also removed the license plates from the black sedan that they were driving at the time of the supposed abduction of Gooden. Even though this lynching received national press coverage, and was the subject of many condemnatory editorials in southern white newspapers, the Wagner-Van Nuys Anti-Lynching Bill remained stalled in the United States Congress well into 1938. The Roosevelt Administration remained relatively silent on the increased outbreak of lynchings during 1937. The executive branch of the government did not want to force an open split with the southern Democrats over the question of racial violence carried out againt African-Americans.

The events of the 1930s illustrated that mob violence against African people was still a mechanism utilized to discourage and neutralize resistance and opposition to white supremacy. Even though the method of execution had shifted from the large scale public murders of African-Americans with hundreds or thousands of spectators cheering on, to the more sophisticated killings done by smaller groups of vigilantes who carried out these actions away from public view, the likelihood of justice being served was almost nil. This shift could be related to the debates within Congress over the passage of the anti-lynching bills of the 1920s and 1930s. These events of the late 1930s created the atmosphere that lead to our second case study of terror during the Great Depression, namely the lynching of Elbert Williams.

The Lynching of Elbert Williams in Haywood County, Tennessee (1940)

Another major incidence of racial violence occured during the month of June in 1940, when members and supporters of the Brownsville, Tennessee branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) were targeted for disruption and liquidation by the Haywood County white establishment for an attempt they were making to register to vote in the national presidential elections of that year. These events culminated in the kidnapping and lynching of Elbert Williams, whose beaten and bullet ridden body was found on June 23 in the Hatchie River outside Brownsville, near the border with Tipton County. Other persons associated with the local voter registration effort were forced to leave the area under threat of murder.

Racial tensions began to intensify in the Brownsville area after the formation of the NAACP chapter in the County by Ollie S. Bond and his associates in 1938. The following year when it became public that the leadership would encourage African-Americans in the County to register and vote in the elections of 1940, the Bond family was threatened with death and driven into exile as a result of a plot to bomb their home, which was carried out in their absence on December 24, 1939. African-Americans, who constituted 61 percent of the Haywood County population in 1940, had been denied the franchise since the late 1880s, when their black state legislator, Samuel McElwee, was forced from public office in Nashville as a result of the white racist campaign to overturn the civil rights laws passed during the Reconstruction era.

Survivors of the June 1940 terror campaign reported that a white mob led by County Sheriff Tip Hunter, visited individual households of NAACP leaders and supporters beating and threatening them with murder if they did not immediately provide information on the voter registration project and agree to leave the area. The widow of Elbert Williams later stated that she believed her husband was killed because he could not tell the law enforcement posse the whereabouts of NAACP leaders Reverend Buster Walker and Elisha Davis, who had recently fled the County. Davis abandoned his gas station business and immediate family under threat of death from the white officials in Brownsville.

Davis, in a public letter written from another Tennessee town, that was published in the Atlanta Daily World on July 16, 1940, stated that: "I gambled everything, my home, my business, my life, my family (wife and children) in order to prove to those people in Brownsville that the NAACP was all right. At present I am separated from my family. I am not making any money. I do not feel secure in the least. After having told all in this case, my life here, even in this town, is constantly threatened."

There was never a record of any indictments handed down by the Haywood County Grand Jury involving the brutal murder of Elbert Williams. Leading officials in the County who were involved in his murder continued to hold office and maintain influence in the area well into the 1960s. Following a similar pattern as the events of 1937 in Tipton County, white official mob violence went unpunished by the state and the federal government.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Abayomi Azikiwe is the editor of the Pan-African News Wire. The above article originally appeared in the Pambana Journal published by the Pan-African Research and Documentation Project in the Winter of 1998 at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan. The article appeared in a monograph entitled: "African Resistance and Genocidal Violence, From Slavery to the Great Depression."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

No comments:

Post a Comment