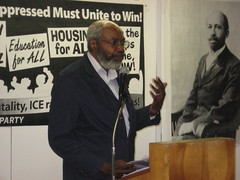

Abayomi Azikiwe, editor of the Pan-African News Wire, speaking at the Workers World African American History Month forum on February 28, 2009. (Photo: Cheryl LaBash)

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire File Photos

The humanity of Africans is consistently reaffirmed through anti-capitalist movements

by Abayomi Azikiwe, Editor

Pan-African News Wire

Editor's Note: The following talk was delivered at a Workers World African American History Month public forum held in Detroit on February 28, 2009.

Two factors have been indispensible in the rise of world capitalism and imperialism: the exploitation of African labor and the theft and utilization of natural resources from the continent. Since the middle decades of the 15th Century the European nations of Spain and Portugual began a process of social violence and political repression against the peoples of Africa. Even today, in the 21st Century, the continent of Africa and its people who have been scattered all over the world, have still not overcome the legacy of slavery, colonialism and imperialism.

However, the conquering and abuse of Africans has not been met with passivity and alienation. Although the ruling class spokespersons and other ideologues of the imperialist system have attempted to distort the developments in the world over the last five centuries, any objective analysis of African history since the advent of slavery illustrates a constant effort on the part of the masses of people to not only resist and overthrow their oppressors, but to also create societies devoid of exploitation and oppression.

Such a response to the invasion and occupation of the African continent and the kidnapping of its people and their enslavement both at home and abroad, should not be suprising. It has been documented extensively that the first cultures and civilizations arose on the African continent.

In the Nile Valley region which encompasses what today is known as Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia and Uganda and Kenya, the early forms of societal organization and technology developed. The disciplines of architecture, chemistry, biology, written language, complex religious systems and philosophies can be traced to these areas of the continent.

In the field of archaeology, researchers have unearthed the remnants of early humanity in east Africa. Even contemporary genetic and biological research has suggested that all of humanity originated from the African continent.

Continuing into the so-called middle ages in Europe, when that continent was struggling with its own identity and development of stable societal structures, the African people had built large settlements, cities, kingdoms and states in various regions of the continent. To provide just a view examples of this historical process it is necessary to point to some of the well-known achievements.

African Societies and the Rise of Imperialism

The Christian civilizations of Nubia, in what is known today as Sudan, arose as early as the 6th Century. In addition, ancient Ghana developed out of various indigenous groups which came together between the 4th and 11th Centuries. The civilization of Ghana was the precursor to the development of ancient Mali, which matured in the early 13th Century.

Songhai, which developed in the late 15th Century, was largely a Muslim civilization that had a tremendous impact throughout west and north Africa.

In the southwest region of the continent was the location of the early Angolan and Congolese civilizations that fought slavery and colonialism between the 16th and 17th Centuries. The Kingdom of Mutapa, in what is known today as Zimbabwe, was so spectacular that the racist explorers attempted to deny that it was a product of African peoples. In the areas known today as South Africa and Lesotho, some of the earliest cultures and their artistic offerings are still present to provide evidence of the true origins of human society and civilizations.

Nonetheless, the intervention of the Atlantic slave trade, the rise of European colonialism and imperialism and the post-independence phenomena of neo-colonialism has impeded Africa and its people from moving toward genuine political and economic liberation. All during the course of these oppressive phases of African history, the people have continued to create to forms of struggle to meet the challenges of the period.

This struggle has been from the onset an international one centered around fundamental economic issues, i.e., labor and natural resource exploitation, the terms of trade and the allocation of profit. The European countries linked the seizure of land in the so-called "New World" with the removal and extermination of the Native peoples and the capturing and importation of African labor into the entire colonial process.

Eric Williams wrote in his classic book entitled "Capitalism and Slavery" (1944) that a convergence of the interests of the monarchy, merchants and the Catholic Church provided the organizational basis for the Atlantic slave trade:

"When in 1492 Columbus, representing the Spanish Monarch, discovered the New World, he set in train the long and bitter international rivalry over colonial possessions for which, after four and a half centuries, no solution has yet been found.

"Portugal, which had initiated the movement of international expansion, claimed the new territories papal bull of 1455 authorizing her to reduce to servitude all infidel people. The two powers, to avoid controversy, sought arbitration and, as Catholics, turned to the Pope a natural and logical step in an age when the universal claims of the Papacy were still unchallenged by individuals and governments.

"After carefully sifting the rival claims, the Pope issued in 1493 a series of papal bulls which established a line of demarcation between the colonial possessions of the two states: the east went to Portugal and the west to Spain. The partition, however, failed to satisfy Portuguese aspirations and in the subsequent year the contending parties reached a more satisfactory compromise in the Treaty of Tordesillas, which rectified the papal judgement to permit Portuguese ownership of Brazil."

Despite these claims by Portugal and Spain as well as other subsequent western European colonial powers, Africans resisted the onslaught of political domination and economic exploitation. There have been a number of historians who have documented the patterns of slave resistance, rebellion and revolt, in an effort to illustrate the humanity of the African people which the colonialist and slave owners attempted to deny.

Slavery and Pan-African Revolt

Herbert Aptheker in his book entitled "American Negro Slave Revolts" (1943), set out to narrate the continued rebellious character of the African community in the western colonies. The question of fear is important in the entire process of effecting the slave system. The notion that the African was most ideally suited to serve the white man was advanced by the ruling class in order reassure themselves that their captive labor force would not refuse to work, runaway, destroy the master's property or engage in revolt.

Aptheker says in Chapter II entitled "The Fear of Rebellion" that:

"While there is a difference of opinion as to the prevalence of discontent amongst the slaves, one finds very nearly unanimous agreement concerning the widespread fear of servile rebellion. This is true not merely among those historians who show some awareness of mass unrest, but even among the larger number who either ignore or positively deny widespread plots and revolts."

Aptheker continues to examine this historical occurence within the psyche of the slave master class by pointing out how European and European American historians respond to the idea of a rebellious slave population. Aptheker makes reference to historians from various ideological orientations:

"Thus, references to this fear, not infrequently joined with an expression of wonder at its presence, are to be found in works dealing with the institution of slavery in Massachusetts, New York, Tennessee, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. The same is true of more extended studies by such scholars as James Schouler, Herbert L. Osgood, William E. Dodd, Carl R. Fish, Emory Q. Hawk, and Ulrich B. Phillips.

"Very recently Clement Eaton devoted several pages to a discussion of this phenomenon. Of course, the discovery of a plot or the suppression of a rebellion, if publicized, invariably evoked fear--indeed, terror--but these manifestations will be noted as they occurred. There is also evidence that this fear existed quite independent of any connection with an actual outbreak." (p. 18)

Why should the fear of resistance and rebellion strike such a sense of terror into the slave master class? It is the irreplaceable role of African labor in the entire economic system of slavery. This dependence on the labor of the captive nation was not only due to the predominance of African labor in the agricultural and domestic realm of production but also in the craft and industrial sectors.

Origins of the African Working Class

The African slave laborers were involved in every major industry operating within the South. One noted southern novelist Nelson Page, wrote at the conclusion of the Civil War in 1865 that Africans constituted "without rival the entire field in industry labor throughout the South." Page went even further and claimed that "ninety-five percent of all the industrial work of the southern states" was carried out by the slaves.

The African artisan and mechanic oftentimes was not confined to the plantation system. In urban areas these slaves were hired out by their masters to work in the fields of carpentry, animal husbandry, and production. Consequently, the skills utilized by the Africans gave them greater mobility and access to resources. In some instances, these slaves were allowed to earn money on their own. There were those who utilized these earnings to purchase their freedom and the release from enslavement of their family members.

In the South at the conclusion of the antebellum period (1790-1861), approximately 90 percent of the African people were enslaved. The existence of "free blacks" in the South was a problem for the white slave owning class as a whole. The condition of the so-called free blacks was highly precarious. They were subjected to institutional racism, harrassment and sometimes re-enslavement.

Even in the North where slavery was outlawed leading up to the Civil War, Africans were by no means free of racism, national discrimination and oppression. About five percent of the African population lived in the northern states during the period leading up to the Civil War. The Africans residing in the northern states had more personal freedom, but at the same time they did not have any guarantees of employment, housing or other amenities offered to the whites.

According to Philip S. Foner and Ronald L. Lewis in their study entitled "Black Workers: A Documentary History From Colonial Times to the Present" (1974), in the northern states fewer Africans had access to the skill trades of the times. The utilization of discriminatory laws and social practices served to keep blacks confined to menial work which inherently paid smaller salaries, and as a result, kept the majority of the population in this region in poverty.

Foner and Lewis indicate that:

"Consequently, black workers in the North suffered more from economic deprivation, poor education, inadequate housing, and nutritional maladies than whites. Their precarious social, economic, and political position meant that they would compete for jobs with newly arrived immigrants, such as the Irish, who learned very quickly that blacks were a ready scapegoat." (p. 3)

The same above-mentioned authors also pointed out the terror tactics carried out by white racists in the economics sphere:

"When blacks could find employment in the North, they frequently encountered white mobs who drove them from their jobs. The 1834 riot in Philadelphia, for example, was precipitated by the convictions among white workers that whites could not find jobs because employers preferred to hire blacks.

"The most dramatic evidence of the powerlessness of northern blacks, however, was the frequency with which blacks were kidnapped by unscrupulous whites who, sometimes in collusion with local officials, whisked them off to the South to be sold into slavery." (p. 3)

In the northern cities many Africans were confined to occupations in the hotels, restaurants, and saloons. Nonetheless, the poor wages and working conditions lead to the formation of labor organizations. In New York City, even prior to the Civil War, the Waiters Protective Association was formed by Africans employed in the industry. The organization was so successful that they advised some white counterparts on how to form a separate group.

The prevailing ideology of racism in the northern areas prevented whites from accepting Africans as their counterparts within an industrial organization or employee association. For example, the leader of the Typographical Union in Philadelphia, John Campbell, published a book at his own expense which propagated the believe that African people were inferior to whites and should not be involved in an organization alongside European Americans.

In the northern areas where Africans were subjected to national discrimination and oppression, some began to organize to improve their conditions. The American League of Colored Laborers was formed in New York City in 1850. The Vice President of this organization was anti-slavery agitator and abolishionist, Frederick Douglass.

The League was concerned about the disadvantaged situation of black laborers and sought to advance unity among the workers operating as mechanics and artisans. In addition, the League sought to promote training in agriculture, commerce and the industrial arts, including the establishment of businesses themselves.

Another current operating at the time was the advent of the Convention movement that brought together African people yearly beginning in 1830. Foner and Lewis reports that:

"The Negro Convention movement was another insitutional response to the problem of restricted labor mobility. During the Antebellum Era, black leaders gathered in conventions, on both the local and national levels, to discuss issues of mutual concern and to reach some agreement as to an appropriate group response.

"One of the most interesting corrective proposals called for the construction of an 'industrial college' for black youth. This idea gained currency at several conventions during the 1840s and 1850s, and won the support of the most prominent black leaders. Unfortunately, no funds could be obtained for an industrial college before the Civil War." (5)

The General Strike and the Civil War

Historian W.E.B. DuBois in his book entitled "Black Reconstruction: An Essay Toward A History Of The Part Which Black Folk Played In The Attempt To Reconstruct Democracy In America, 1860-1880", makes the claim that in response to the split within the American bourgeoise, where the northern industrialists and the southern planters went to war over the economic future of the United States, the nearly 4 million Africans enslaved in the South engaged in a general strike.

Since the Union army and the federal government did not see a direct role for the work force of the slave system, it was no use seeking a solution with the military forces of Lincoln. Eventually by the middle of 1862, the Lincoln administration understood that the African people would have to be brought in as soldiers in the Union Army in order to win the war against the Confederacy.

DuBois says in "Black Reconstruction" that:

"It must be borne in mind that nine-tenths of the four million black slaves could neither read nor write, and that the overwhelming majority of them were isolated on country plantations. Any mass movement under such circumstances must materialize slowly and painfully. What the Negro did was to wait, look and listen and try to see where his interest lay.

"There was no use in seeking refuge in an army which was not an army of freedom; and there was no sense in revolting against armed masters who were conquering the world. As soon, however, as it became clear that the Union armies would not or could not return fugitive slaves, and that the masters with all their fume and fury were uncertain of victory, the slave entered upon a general strike against slavery by the same methods that he had used during the period of the fugitive slave. He ran away to the first place of safety and offered his services to the Federal Army.

"So that in this way it was really true that he served his former master and served the emancipating army; and it was also true that this withdrawal and bestowal of his labor decided the war." (p. 57)

The war would take nearly four years to complete before Lincoln's soldiers would finally triumph over those of Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee. The South was left economically devastated and structurally destroyed. It has been reported that approximately 186,000 African soldiers fought in the Union Army to end slavery and preserve the United States as a nation.

In 1863 the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect granting freedom to the Africans in the slave states. A greater incentive was provided for the slaves to leave the plantations and work toward the eventual defeat of their masters. With the economic basis of the system collapsing rapidly, the eventual rise and predominance of industrial capitalism was assured.

Under these conditions as well, the African masses would continue to play a pivotal role in the economic development of the United States and the capitalist world. Nonetheless, even after the Civil War concluded with the defeat of the Confederacy, it would take another 100 years to bring any significant weakening of the social system of racial segregation and racial capitalism in the South.

The fact of the matter was what DuBois described also in "Black Reconstruction":

"The South counted on Negroes as laborers to raise food and money crops for civilians and for the army, and even in a crisis, to be used for military purposes. Slave revolt was an ever-present risk, but there was no reason to think that a short war with the North would greatly increase this danger. Publicly, the South repudiated the thought of its slaves even wanting to be rescued.

"The New Orleans Crescent showed 'the absurdity of the assertion of a general stampede of our Negroes.' The London Dispatch was convinced that Negroes did not want to be free. 'As for the slaves themselves, crushed with the wrongs of Dred Scott and Uncle Tom--most provoking--they cannot be brought to 'burn with revenge'. They are spies for their masters. They obstinately refuse to run away to liberty, outrage and starvation. They work in the fields as usual when the planter and overseer are away and only the white women are left at home.'"

Such a delusional outlook on the part of the southern planters would inevitably lead to their defeat in the war. However, the old system of slave labor would not be ended with the conclusion of the war.

Toward the Self-Organization of African Labor

During the Reconstruction period, the commitment of the federal government was not adequate. By the conclusion of the 1860s, there were white vigilante organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan, which was formed by former Confederate military officials such as Nathan Bedford Forrest, that targeted Africans and radical politicians. By the conclusion of the 19th Century the system of institutional racism had been securely established.

Donald G. Nieman, editor of "African Americans and Non-Agricultural Labor In The South, 1856-1900", wrote in the introduction that:

"African American workers played an integral role in the economic life of southern cities and towns. As they had during slavery, blacks continued to work as carpenters, plasterers, painters, blacksmiths, masons, and common laborers, providing the skills and muscle essential to urban growth. They played a vital role in transportation, working as teamsters, on the docks as stevedores, and on the railroads as section hands, firemen, porters, and brakemen.

"African Americans were also prominent in the service sector, where they worked as barbers, cooks, waiters, laundresses, and domestic servants. Black women, who were far more likely to work outside the home than white women, were especially important service workers, providing most of the South's domestic servants and laundresses. In an age before labor-saving household appliances, they performed arduous household chores, contributing to the quality of life of white middle-class families." (P. viii)

Despite the large scale African labor force which entered into direct competition with whites after the conclusion of the Civil War, the practice of racial exclusion prevailed in the unions. One stark illustration of this policy was the exclusion of Lewis H. Douglass, the son of Frederick Douglass, from the Columbia Typographical Union in Washington D.C.

When Douglass challenged the exclusion, his detractors claimed that the denial was not based on race but that he had worked as a printer in the West without being a union member. Douglass and his allies waged a struggle around this issue which was covered in a weekly African American newspaper, the New National Era, published in Washington, D.C. However, many other craft unions responded to this struggle with policies that actually enhanced the racial exclusivism of their labor organizations.

There was one outspoken newspaper that supported Douglass in the dispute over the racist action. The Boston Daily Evening Voice not only believed that Douglass should be admitted into the Columbia Typographical Union, but it also championed solidarity and unity among both black and white workers. The paper's editorial position was that the white workers could not ignore or engage in discrimination against black workers because it would undermine their on power as a class.

The Boston Daily Evening Voice had editors who were previously associated with the Abolitionist movement and supported black labor rights within the context of fulfilling the promises of a radical reconstruction of the United States after the conclusion of the Civil War and slavery. Nevertheless, the policy of the Voice was not accepted by the dominant trends within the white labor organizations.

The first labor federation to be formed in the aftermath of the Civil War was the National Labor Union (NLU) which was founded in Baltimore in 1866. Approximately 60 delegates attended the Baltimore inaugural gathering and were said to represent some 60,000 workers. At this meeting the plight of African workers was raised in a document entitled "The Address of the National Labor Congress to the Workingmen of the United States." The document was presented at the 1867 convention and stated in part that "Unpalatable as the truth may be to many, Negroes now occupied a new position in America, and the actions of white workingmen would determine whether the ex-slaves would become an element of strength or an element of weakness" in organized labor.

Nonetheless, the call to address the plight of African working people went unheeded. The Boston Daily Evening Voice criticized the NLU for its refusal to take actions aimed at the organization of African workers. The Voice declared that it was a "disgrace that several members were so much under the influence of the silliest and wickedness of all prejudices as to hesitate to recognize the Negro." The paper went on to argue that the labor movement dominated by whites would "never succeed till wiser counsels prevail and these prejudices are ripped up and thrown to the wind." (Foner and Lewis, p. 9)

By 1869, the NLU convention was attended by a delegation of African American workers. The convention still did not go on record as favoring a unified labor movement but instead called upon the organization of African workers into separate labor organizations. Isaac Myers of the Baltimore Colored Caulkers' Trade Union Society, addressed the NLU convention that year. Just four years prior to this event, in 1865, the white caulkers and carpenters had attacked their black counterparts and driven them from the shipyards where they worked.

It was this incident that lead to the organization of his union in addition to the Chesapeake Marine Railway and Dry Dock Company that contracted the three hundred workers who were forced from their jobs. Myers would be a prominent figure in the struggle of African workers for many years.

On July 20, 1869, the State Labor Convention of the Colored Men of Maryland called for the convening of an African labor conference in December of that year. At this meeting Colored National Labor Union was formed.

According to Foner and Lewis:

"The delegates lost little time addressing the problems of black workers. They established a permanent National Bureau of Labor with offices in Washington, D.C., to furnish informaiton about employment opportunities in various parts of the nation, to lobby for legislation insuring equality of employment opportunity, and to negotiate with 'bankers and capitalists' for financial assistance in establishing cooperative business ventures among blacks. The bureau, composed of the chief officers and nine-man executive committee of the CNLU, was direct in its declaration that the 'question of the hour' was how the black worker could 'best improve his condition.' The CNLU also encouraged blacks to organize at the state and local levels, cooperatively pooling their wealth, since 'without organization, they would stand in danger of being exterminated.'" (Foner and Lewis, p. 11)

Unfortunately other objective factors would prevent the CNLU from reaching its full potential. The failure of Reconstruction and the prevalence of white racist para-military organizations such as the KKK terrorized African workers and their families and in many cases drove them away from their places of employment.

By the time that the federal government had abandoned its national policy through the Republican Party for Reconstruction in the South, the CNLU had began to seriously decline. With the failure of most white workers to support the advancement of African labor, the only option black workers had was to continue their alliance with the Republican Party. The Republicans had no real program for the economic equality of the African masses.

Foner and Lewis point out that despite its short-lived existence the CNLU did have positive effects:

"Even though its life was short, the CNLU influenced the founding of numerous state labor organizations among blacks. The most significant spin-off organization established in the South was the Alabama Negro Labor Union (ANLU), founded by James Rapier. An officer in the CNLU, rapier labored vigorously to organize black workers in Alabama. After conferring with local black leaders, he agreed to spearhead a state labor convention at which delegates would discuss 'the working conditions of colored farmers in Alabama,' possible sites where blacks might emigrate, and educational opportunities available for blacks in the state.

"After thoroughly investigating those topics, about fifty black delegates from across the state gathered in Montgomery on January 2, 1872, to discuss their findings. The proceedings of the ANLU convention were presented in 1880 before a U.S. Senate Committee investigating the causes of the Kansas Exodus of 1879. Today, little of the ANLU's history can be reconstructed, but records indicate that the organization was still active in November 1873." (Foner and Lewis, p. 13)

Black Militancy and The Knights of Labor and the AFL

Two other labor federations would gain predominace during the later years of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century. The Knights of Labor was formed in 1869 and began a campaign to recruit African workers. The formal policy of the Knights of labor was not to exclude any man based upon race. Women were not admitted until 1881.

Africans in the South responded enthusiastically to the possibility of joining a labor organization. However, the white ruling class elements in the South responded in many cases with violence against African Americans who sought to challenge the slave-like conditions in operation during the post Civil War period between the late 1860s and the 1880s. In Little Rock, Arkansas in July of 1886, three assemblies of the black Knights of Labor had organized a strike demanding an increase in wages and better working conditions.

White landowners declared the strike an act of rebellion and subsequently organized a militia to break the work stoppage. By 1886, African Americans numbered 60,000 within the 750,000 member Knights of Labor. In certain southern states the membership among African Americans grew rapidly. In Virginia, Africans constituted 50 percent of the Knights 15,000 members. Nonetheless, many Africans felt that the union leadership was not taking a militant stand in regard to demanding full equality for its membership.

The discontent within the Knights of Labor came to a boiling point when in 1886 the organization would hold its national convention in Richmond, Virginia. Frank J. Ferrell, an engineer and the only member of the New York delegation to the convention, had gained considerable notoriety as the most prominent African American in the labor movement. Ferrell was recognized in the black community as a militant and a socialist. However, the convention announced before it began that Ferrell would not be given accomodations at the hotel where the convention was taking place.

Perhaps the most critical events occured in 1887 when the sugar workers in Louisiana went on strike for higher pay and better working conditions. This was not the first time that there were strikes in the sugar industry. Previous attempts were broken when state militias were formed by the landowners and politicians which drove the workers back to the plantation work places at gun point.

In an effort to break the strike of November 1887, the sugar plantation owners agreed to a $1 a day wage on the condition that the Knights of Labor not be recognized as the bargaining agent for the workers. The African workers refused this offer and continued the strike. Soon enough many black leaders of the strike were harrassed, beaten and arrested by the authorities. African American families were driven out of their homes and two arrested men were taken out of their jail cells and lynched. Despite this reign of terror, the national organization of the Knights of Labor did not take militant action in defense of the black workers.

Foner and Lewis pointed out the significant impact of these events on the Knights of Labor as an organization:

"To black workers, the sugar strike of 1887 had been a terrible lesson. Even though nine thousand Negroes had refused to accept a higher wage in order to secure the recognition of their union, that same organization refused to support them. Once again a union demonstrated to black workers that labor solidarity was an ideal that did not include Negroes, and in the end this realization helped to undermine the Knights of Labor.

"As it became increasingly clear that most white Knights were refusing to accept the principle that black and white economic problems bound workers of both races together in a common cause, and as the somewhat opportunistic strategy of the national leadership became more and more apparent, interest among black workers began to fade. By 1890 it ceased to exist at all. By then the Order had abandoned the black worker, as many Negroes suspected it would all along and refused to take a stand even in general terms against the rising tide of racial segregation. In 1894 the Knights announced that the only solution to the "Negro Problem' in the United States was to raise federal funds for the deportation of blacks to Africa." (p. 19)

By the mid 1890s, the Knights of Labor had gone into rapid decline. In 1895 they were virtually non-existent as an effective labor organization.

In the aftermath of the decline of the Knights of Labor, the American Federation of Labor began to gain prominence in the 1880s and 1890s. Nonetheless, the AFL maintained some of the same racial policies that served to undermine the Order. Samuel Gompers, the leader of the AFL, made public statements to the effect that the interests of African American workers could not be ignored because it would ultimately have a negative impact on their white counterparts.

However, many white workers refused to accept the organization of their African American counterparts as essential. A significant number of whites opposed the recruitment, organization and membership of African Americans within the AFL. Therefore, to the extent that Africans were involved in the AFL, they were organized in many cases into separate locals based on race. When whites opposed the granting of charters to these racially segregated locals, the national leadership of the AFL did not insist that these racist policies be overturned.

During the first two decades of the 20th century racial tensions in the United States escalated. There were white mob attacks on African communities in Atlanta in 1906 and Springfield, Illinois in 1908. With the commencement of World War I, racial antagonism boiled over through incidents involving black servicemen during 1917. The conditions of African American soldiers in France during the War have been well documented.

After the conclusion of World War I a series of race riots erupted throughout the United States, with the most well known taking place in Chicago during the so-called "Red Summer" of 1919. During the 1920s, migration of African tenant farmers and workers into the northern industrialized cities would continue at an accelerated pace.

The collapse of the United States economy in 1929, sent shockwaves throughout the society as a whole. African Americans were deeply affected by these developments since their economic position was far more precarious than their white counterparts. However, during this period, Africans joined nationalist and socialist political formations including the Communist Party. Eventually, as a result of the labor upheavals of 1934, the Committee of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was formed in 1935. This formation and its approach to organizing black labor would usher in a new era of working class struggle in the United States.

The CIO and the UAW: Struggles From the 1930s to the 1960s

With the New Deal policies of the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, a new emphasis was placed on the plight of the unemployed and impoverished within the United States. These new programs grew out of the labor and mass struggles of the early and middle 1930s. In theory the burgeoning industrial unions of the CIO did not oppose the non-discrimination provisions in the Wagner Act. The AFL affiliated unions that formed the CIO had already taken a position at variance with the other organizations that upheld the racist practices of the white dominated locals and national officials.

Consequently, the CIO had an advantage over the AFL in that the production industries where many African Americans were concentrated, such as meat-packing, auto, rubber and steel, were increasingly organized by the new labor federation. Even in the South where AFL locals had rejected African workers support during the 1917 tobacco industry strike, would by 1936 be organized by the CIO. Also the National Maritime Union (NMU), which was formed in 1937 accepted African American seaman on an equal basis. As a result its black membership flourished resulting in the election of Ferdinand C. Smith, an African American co-founder of the NMU, as first secretary and vice-president.

During this period, the CIO supported black organizations such as the National Negro Congress (NNC), which was a broad front of African American organizations that encompassed liberals, socialists and communists. When the AFL expelled the CIO in 1937 under the charge of dual unionism, the CIO had already established thirty-two international unions. In 1938 it officially changed its name to the Congress of Industrial Organizations.

In regard to the recognition of the United Auto Workers union in Detroit in 1941, the participation of African American workers was essential. Henry Ford's paternalism toward the black community had bought the loyalty of a number of key church leaders and businessmen. However, the support for UAW recognition was sealed when major African American organizaitons such as the NAACP and NNC convinced the 17,000 black workers at Ford to not allow themselves to be used by the corporation. Consequently, on April 11, 1941, Ford gave in to the strikers demands and recognized the UAW.

During the years of American involvement in World War II (1941-1945) more Africans migrated to the northern industrial states. Employment grew and support for the UAW and the CIO reached historic proportions. However, after the war the governments FEPC policy was revoked and discrimination was no longer an issue in industry. This was of course influenced by the return of millions of white and black workers to the U.S. labor force that fueled competition for jobs and housing in American towns and cities.

The revolutions in Vietnam, Korea and China as well as the expansion of the influence of the Soviet Union in the aftermath of World War II became the central focus of U.S. capitalism and imperialism. In addition, the national liberation struggles in Africa, Asia and Latin America gained strength. The post World War II period was one of optimism and intensive efforts aimed at ending colonialism and racism throughout the world.

This new atmoshpere influence the leadership of the CIO when in 1949, it barred executive committee members from belonging to the Communist Party and other left organizations. Later there was the expulsion of five thousand members of the United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers of America. Other Unions refusing to accept the Cold War policies of the Truman administration were also expelled.

As a result of these political developments, the non-discrimination policies of the official trade union movement was crushed. In 1950, there were efforts made to organize against racial discrimination in the labor market. That June, a National Labor Conference for Negro Rights was convened. By the following year plans were formulated to establish a permanent organization that was formed in Cincinati on October 27, 1951. The organization became known as the National Negro Labor Council. The NNLC set two major objectives: to eliminate job discrimination against African Americans in industry and to also crush institutional racism within the union movement itself.

However, the NNLC became an immediate target of the right wing anti-communist forces controlling the federal government and the union movement. NNLC leaders were called before Congress and accused of being communists and disloyal to the United States. Eventually the organization was forced to dissolve. The struggle against racism in industry and in the trade union movement suffered a serious setback.

Despite these problems, a new phase of the civil rights movement was to emerge with the Montgomery Bus Boycott in December of 1955. Some of the key leaders in the Boycott, such as E.D. Nixon and Rosa Parks had been affiliated with the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the NAACP. The mass support for the civil rights movement by 1960 was forcing the recently merged AFL-CIO (1955) to at least pay lip service to non-discrimination.

By the late 1960s, with the emergence of the Black Power movement, African American workers took on a more militant posture in regard to fighting racism in industry and within the unions. The formation of the Freedom Labor Unions in the South in 1965 and the Revolutionary Union Movements in the plants in Detroit and other parts of the country in 1968, had a tremendous impact. Black workers began to engage in agitation and wildcat strikes independent of the more conservative union leadership.

The Transformation of Capitalism and the Working Class

However, by the 1970s, the United States economy began to sink into a protracted crisis of a political nature. The Vietnam War drained the state of much needed resources to end racism and poverty. The impact of automation and the shifting of industrial facilities to the non-unionized areas of the South and outside the United States increased unemployment and the decline in real wages. This trend was also influenced by the Arab oil embargo in 1973.

With the advent of Reaganism in the 1980s, the conditions of working people declined further. African American workers were most seriously affected in this process. By the beginning of the 1990s, more militant action was required. The rebellions of 1992, signalled the discontent of African and Latino workers in California and other parts of the country. The number of African Americans in industry had declined significantly and the rise of a new phase of militarism hampered any possibility of an employment-driven economic recovery.

Today the decline in the capitalist system is quite evident with the rising unemployment rates, epidemic home foreclosures and evictions and the militarist policies of the United States ruling class. Just over the last year more than three million workers have been thrown out of their jobs. The crisis has now beome a political one due to the fact that every program aimed at improving the economy only results in worsening conditions for the working class.

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have further wasted trillions of dollars of tax monies from working class families. Even Democratic Party politicians in the Congress and White House, who are elected with a mandate to end wars, reduce military budgets, create jobs and establish a national health insurance program cannot do so because of the symbiotic relationship between this party and the bourgeosie.

Nonetheless, the political, economic and ideological collapse of capitalism and imperialism provides openings for the African peoples and the working class in general. There have been efforts organized to impose state and federal moratoriums on home foreclosures and evictions. A rebellion in Oakland illustrated the growing anger and frustration of young people who have no future under the capitalist system.

However, there is much more to come in the months and years ahead. The terminal crisis of capitalism is worldwide. The banking systems from Asia to Europe and the United States are rapidly crumbling. The is no future for the working class and the nationally oppressed outside of socialism and genuine national liberation.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Abayomi Azikiwe is the editor of the Pan-African News Wire. The writer has been a researcher for many years in the areas of African and labor history in the United States and the world.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 comment:

China has just started using biologically cloned humanoid drones in its factories and military to counter the greying of the population caused by their former one child policy. This biological experimentation had begun in the early 1990s to produce star athletes but was aggressivley advanced. Such drones ahve also been know to appear on American soil as illegal workers. Given they blatant disregard for American safey in products they sell, because they don't care if we stay alive after we enrich them, it is worrisome that these clones have not been adequately tested for potential disease transmission.

Post a Comment