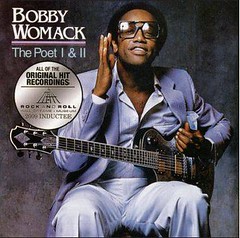

Bobby Womack on a compact disc cover was recently inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in his hometown of Cleveland, Ohio.

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire File Photos

April 05, 2009 10:58 AM ET

Gary Graff, Cleveland

After inducting Bobby Womack into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on Saturday night in Cleveland, Ron Wood said that he's recorded about a dozen songs for a solo album called "More Good News." During an after-party at the House of Blues, producer Bob Rock confirmed that he worked on an as-yet-untitled track with Wood which features a guest appearance by Pearl Jam's Eddie Vedder.

Womack, meanwhile, predicted that Wood's album -- his first studio outing since 2001's "Not For Beginners" -- "is gonna be great" and acknowledged he's "trying to get on it."

Also hatching future plans is soul great and Hall of Fame inductee Sam Moore. "As we talk it's happening," Moore, who performed at the House of Blues after-party, told Billboard.com at the ceremony. "Hopefully before the year's over we're gonna go back in the studio. We're gonna cover a lot of stuff people wouldn't even think that Sam would do." It will be Moore's first recording project since "Overnight sensational" in 2006.

Links referenced within this article

Find this article at:

http://www.billboard.com/bbcom/news/ron-wood-taps-eddie-vedder-bob-rock-for-1003959010.story

Rock Hall inductee Bobby Womack: A low-key musician with a storied career

His work is woven into rock music lore

Sunday, March 29, 2009

John Soeder

Plain Dealer Pop Music Critic

Los Angeles -- He was best friends with Sam Cooke. He played on records by Elvis Presley, Aretha Franklin and Sly and the Family Stone, to name just a few.

And when he gave Janis Joplin a ride in his luxury car, she was inspired to write "Mercedes Benz," right before she died.

"It's amazing where life can take you," says Cleveland native Bobby Womack.

A red baseball cap is pulled low over his head. Over the years, he's worn a lot of other hats. Hit-making R&B singer-songwriter. Left-handed hotshot guitarist. In-demand studio musician.

Womack turned 65 this month. He lives around the corner from the hip bustle of Ventura Boulevard, although he leads a fairly low-key existence these days.

Looking down from gilded frames on a wall in his modest apartment are portraits of his father, Friendly Womack, and Cooke.

On the cluttered coffee table, candy dishes filled with jelly beans vie for space with autobiographies by Richard Pryor, Motown founder Berry Gordy Jr. and Womack's pal Ron Wood of the Rolling Stones.

Womack's own life story has been part Shakespearean tragedy, part "Zelig." Not unlike the main character in the Woody Allen movie, Womack has wandered in and out of key scenes in the history of rock 'n' roll and rubbed elbows with the music's most famous superstars.

Sometimes when he listens to the radio, he'll find himself inexplicably drawn to a song he hasn't heard in ages. Then it hits him.

"All of a sudden, I'll go, I played on that!' " Womack says.

He hasn't always gotten his due. But this veteran soul man is about to get his happy ending, when he returns to his hometown this week to take his place in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Retracing the path that led him there easily consumes the better part of a recent afternoon. Parked on a couch, Womack rattles off one remarkable anecdote after another ("I got close to Sly [Stone] because I kept saying, This is a creative guy. . . .' ") in that deep-fryer voice of his. It sizzles, crackles and spits.

Where to start?

"I would start from the beginning," Womack suggests.

He more or less laid it out in "Across 110th Street," the autobiographical song he composed for the 1972 blaxploitation film of the same name:

"I was the third brother of five

Doing whatever I had to do to survive

I'm not saying what I did was all right

Trying to break out of the ghetto was a day-to-day fight. . . ."

For young Robert Dwayne Womack, that battle was waged in an inner-city neighborhood at the intersection of East 63rd Street and Central Avenue in Cleveland.

"The ghetto was just a way of life," he says. "I remember for Christmas, we would go to Shaker Heights, to see how the rich people lived. . . . It was lit up like you couldn't believe."

He was strictly forbidden from touching his father's guitar, but Womack taught himself to play it (albeit upside-down) while Pop was off at work in the steel mill. Womack, his older brothers Friendly Jr. and Curtis and younger brothers Harry and Cecil learned to sing together by imitating their dad's amateur gospel group, just for laughs.

Before long, their father had his boys singing gospel music at every house of worship in Cleveland. They talked their way into opening for Sam Cooke's Soul Stirrers at Friendship Baptist Church in 1953.

"Man, can you really sing?" Cooke said.

"Yeah -- me and my brothers, we all sing," Womack said. He was 9.

"If I let you open up the show, you're not gonna hurt me, are you?" Cooke said.

"No, I'm not gonna hurt you," Womack said, unaware Cooke was only teasing.

Womack smiles at the memory.

"We tore the place up," he says. "They just went nuts."

Leaving school, leaving home

The Womack Brothers eventually took their gospel show on the road, raising their voices in sanctified harmony at churches, revival meetings and religious conventions.

After gigs, they drove overnight back to Cleveland. Their father would drop them off at East Tech High School, still in their stage clothes.

"We'd all have on these little green suits and yellow shoes," Womack says. "People were laughing.

"This teacher, Mr. Washington . . . he used to always criticize us: You boys ain't learning nothing. They think they gonna be singers. What they'll end up being is janitors.'

"The embarrassment -- that's why we dropped out of school. . . . We did what we thought we should be doing."

Cooke signed the Womack Brothers to his record label, SAR, although he told them there wasn't any money in gospel. He wanted them to follow his lead and make the leap to secular music.

"My father would kill us," Womack told Cooke.

Cooke made a deal with the Womack Brothers: He would release a gospel song as a single, but if the record wasn't a hit, they had to follow up with a rock 'n' roll song.

After the Womack Brothers failed to set the world on fire with their gospel single, they rechristened themselves the Valentinos in 1962 and reworked the gospel standard "I Couldn't Hear Nobody Pray," complete with new lyrics and a new title: "Lookin' for a Love."

It was a smash, but their father wasn't impressed. He kicked his sons out of the house.

"If you're gonna stay here, you're not serving Satan," he said. "If Sam wants y'all to sing that kind of music . . . go live with Sam."

Cooke sent $3,000 to Womack and his brothers, so they could purchase a new car to get them safely to Los Angeles.

Womack had other ideas. He wanted to ride in style, like the neighborhood pimps. The brothers ended up buying a used Cadillac for $600.

Homer's "Iliad" and "Odyssey" had nothing on the ensuing cross-country adventure. Before the Valentinos were even out of Ohio, their car troubles began.

"It started to rain," Womack says. "The windshield wipers swung and went right off the car. I said, Damn!' "

It took them three weeks to get to California. The tires blew out, the engine broke down and the gas tank had a leak. The exhaust fumes made them so ill, they had to go to a hospital in Arizona.

When the Cadillac finally heaved its last on Hollywood Boulevard, Womack found a pay phone and called Cooke.

"Sam was going nuts," Womack says. "He was saying, They should've been here by now. Where they at? We ain't heard from 'em.'

"He said, OK, I'm on my way to get you.' And I'll never forget, he came in a Ferrari to pick us up. He said, Man, I'm just glad I can call your mom and your dad and say, They're safe. They're here.' "

A Change Is Gonna Come'

The Valentinos' next Womack-penned hit, "It's All Over Now," was covered by the Rolling Stones, which gave Mick Jagger & Co. their first No. 1 single.

Womack initially wasn't keen on the idea of the Stones doing his song.

"Somewhere down the line, it'll be one of the greatest moves you ever made," Cooke told him.

Womack reconsidered when he got his first royalty check.

"Looking back on it today, I probably got a small piece of what I was supposed to get," he says. "But it was a big piece."

Stones guitarist Ron Wood is set to introduce Womack during the Rock Hall induction ceremony.

On the road with the Valentinos in the mid-'60s, Womack met another left-handed guitarist named Jimi Hendrix, who at the time was backing Gorgeous George Odell.

Hendrix "would cut his sandwich in half and wrap the other half like he would never eat it again, and a week later, he'd open that sandwich back up," Womack says.

"He played his guitar all the time when we were on the bus, all the time. You could hear that ching-ching-ching scratching sound. But I learned to accept him. . . . I took a liking to him."

On the side, Womack toured and recorded with Cooke, too.

In late 1963, Womack was summoned to Cooke's home. He was excited about a new song he had recorded, "A Change Is Gonna Come," and played it for Womack.

"Tell me your honest opinion," Cooke said.

"It feels like death," Womack said.

"Death?" Cooke said.

"It's great -- it just feels like something terrible happened," Womack said.

Cooke laughed. "I'll never release it then," he said. "I ain't putting it out."

One year later, Cooke was dead. The manager of a Los Angeles motel said she shot him in self-defense when he attacked her. Cooke allegedly had become irate after a woman he took to the motel ran off on him.

The Valentinos were on tour when Womack got the news.

"I felt totally lost," he says.

Three months later, a scandal erupted when he married Cooke's widow, Barbara. Radio stations abruptly stopped playing his music.

"I felt that I could come in and say, Nobody will ever hurt this family -- I'm here,' " Womack says. "I remember Barbara saying to me, Well, if you're coming up here and we're not married, they're gonna talk about us. . . . We should get married.'

"I was very confused, and I got even more confused."

Heartbreak and hardships

When the Valentinos called it quits in 1966, Womack already had lined up a spot in Ray Charles' band.

"Ray was cool to say, Play with me,' " Womack says. "He brought that great big old book out -- looked like a telephone book -- and said, These are the songs.' It was the charts."

Womack told Brother Ray that he couldn't read music.

Charles couldn't believe it. He asked Womack to accompany him on a few songs, to see if he could cut it.

"Every song he played, I was on it," Womack says. "He said, How do you know where I'm going?' I said, I see you before you get there and I just slide into it.' "

In the late '60s, Womack landed a job at American Sound Studio in Memphis. There, he did sessions with the likes of Jackie Wilson, Dusty Springfield and Presley. That's Womack's guitar on "Suspicious Minds."

Womack made a new friend in Wilson Pickett, who scored a hit with Womack's "I'm a Midnight Mover."

Pickett "reminded me of me," Womack says. "He was insecure. He wasn't educated. But he wrote some great songs."

Womack found another kindred spirit in Sly Stone, who tapped Womack to play on his "There's a Riot Going On" album. Other musicians continued to have success with Womack's songs, too.

His off-the-cuff instrumental "Breezin' " was a hit for George Benson.

Womack had a string of Top 40 singles of his own in the '70s, including "That's the Way I Feel About Cha." By then, his five-year marriage to Barbara was over. He later remarried, but his second marriage also ended in divorce.

Against the advice of his record label, Womack put out a country album, "BW Goes C&W," in 1976.

In the '80s, he was back in R&B mode for a pair of well-received solo albums, "The Poet" and "The Poet II." They've just been reissued on one CD.

"I was at my best then," Womack says. "I wasn't thinking about how to say something -- just saying it."

Yet any success he tasted was hard to enjoy. A series of personal tragedies took a toll on Womack. He lost two of his six children -- one suffocated when he fell out of bed as a baby, the other committed suicide -- and his brother Harry was murdered by a jealous girlfriend.

Womack sought comfort in cocaine.

"Through all of the hardships - losing Sam, losing my brother and stuff like that - I'm trying to be a musician, but I lost that because I married Sam's wife and they started comparing me with the greatest artist that ever lived, as far as I'm concerned," he says.

"Everywhere I would go to perform, seems like they would try to compare me with Sam. I said, 'C'mon, man, there's only one Sam Cooke.

"Being under that pressure . . . I picked up the habit."

By the '90s, Womack had cleaned up his act.

"That's the biggest achievement - I got myself right," he said.

"Looking back on all of these creative people, I've seen many of 'em go out. They lose themselves. And if you lose yourself, you lose everything.

"I just wanted to go back to where I was, from the beginning. I knew nothing about drugs, none of that, when I first started singing. I was just singing because I love to sing."

His last new studio album, 1999's "Back to My Roots," was a return to gospel. He dedicated it to his father, who died in 1981.

His mother, Naomi, is coming in for the Rock Hall gala. She lives with Curtis in Norfolk, Va. Friendly Jr. and Cecil no longer live in Cleveland, either.

Womack got a call the other day from Snoop Dogg, who is interested in doing some recording together. Beyond the induction ceremony, though, Womack has no firm plans.

"To be honest with you, I take one day at a time," he says.

"You get to the point where you just say, 'I'm not fighting anymore.' I've said what I said. And people still buy it.

"They can take it any way they want to take it, shape it any way they want to shape it. It's still the truth. And that overrules everything else."

To reach this Plain Dealer reporter:

jsoeder@plaind.com, 216-999-4562

No comments:

Post a Comment