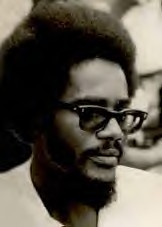

Walter Rodney, a Guyanese-born African historian, wrote extensively on revolutionary thought and political practice. He was based in Tanzania for many years before returning to Guyana where he was assassinated in June 1980.

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire File Photos

Capital and African wage labour

by Walter Rodney, 1972

Reprinted From "How Europe Underdeveloped Africa"

Colonial Africa fell within that part of the international capitalist economy from which surplus was drawn to feed the metropolitan sector. As seen earlier, exploitation of land and labour is essential for human social advance, but only on the assumption that the product is made available within the area where the exploitation takes place.

Colonialism was not merely a system of exploitation, but one whose essential purpose was to repatriate the profits to the so-called ‘mother country’. From an African view-point, that amounted to consistent expatriation of surplus produced by African labour out of African resources. It meant the development of Europe as part of the same dialectical process in which Africa was underdeveloped.

By any standards, labour was cheap in Africa, and the amount of surplus extracted from the African labourer was great. The employer under colonialism paid an extremely small wage – a wage usually insufficient to keep the worker physically alive – and, therefore, he had to grow food to survive. This applied in particular to farm labour of the plantation type, to work in mines, and to certain forms of urban employment.

At the time of the imposition of European colonial rule, Africans were able to gain a livelihood from the land. Many retained some contact with the land in the years ahead, and they worked away from their shambas in order to pay taxes or because they were forced to do so. After feudalism in Europe had ended, the worker had absolutely no means of sustenance other than through the sale of his labour to capitalists.

Therefore, to some extent the employer was responsible for ensuring the physical survival of the worker by giving him a ‘living wage’. In Africa, this was not the case. Europeans offered the lowest possible wage and relied on legislation backed by force to do the rest.

There were several reasons why the African worker was more crudely exploited than his European counterpart in the present century. Firstly, the alien colonial state had a monopoly of political power, after crushing all opposition by armed force. Secondly, the African working class was small, very dispersed, and very unstable owing to migratory practices. Thirdly, while capitalism was willing to exploit all workers everywhere, European capitalists in Africa had additional racial justifications for dealing unjustly with the African worker.

The racist theory that the black man was inferior led to the conclusion that he deserved lower wages; and, interestingly enough, the light-skinned Arab and Berber populations of North Africa were treated as ‘blacks’ by the white racist French. The combination of the above factors in turn made it extremely difficult for African workers to organise themselves.

It is only the organisation and resoluteness of the working class which protects it from the natural tendency of the capitalist to exploit to the utmost. That is why in all colonial territories, when African workers realised the necessity for trade union solidarity, numerous obstacles were laid in their paths by the colonial regimes.

Wages paid to workers in Europe and North America were much higher than wages paid to African workers in comparable categories. The Nigerian coalminer at Enugu earned 1/- per day for working underground and 0/9d per day for jobs on the surface. Such a miserable wage would be beyond comprehension of a Scottish or German coalminer who could virtually earn in an hour what the Enugu miner was paid for a six-day week.

The same disparity existed with port workers. The records of the large American shipping company, Farrell Lines, show that in 1955, of the total amount spent on loading and discharging cargo moving between Africa and America, five-sixths went to American workers and one-sixth to Africans.

Yet, it was the same amount of cargo loaded and unloaded at both ends. The wages paid to the American stevedore and the European coalminers were still such as to ensure that the capitalists made a profit. The point here is merely to illustrate how much greater was the rate of exploitation of African workers.

When discrepancies such as the above were pointed out during the colonial period and subsequently, those who justified colonialism were quick to reply that the standard and cost of living was higher in capitalist countries. The fact is that the higher standard was made possible by the exploitation of colonies, and there was no justification for keeping African living standards so depressed in an age where better was possible and in a situation where a higher standard was possible because of the work output of Africans themselves. The kind of living standard supportable by African labour within the continent is readily illustrated by the salaries and the life-style of the whites inside Africa.

Colonial governments discriminated against the employment of Africans in senior categories; and, whenever it happened that a white and a black filled the same post, the white man was sure to be paid considerably more. This was true at all levels, ranging from civil service posts to mine workers.

African salaried workers in the British colonies of Gold Coast and Nigeria were better off than their brothers in many other parts of the continent, but they were restricted to the ‘Junior staff’ level in the civil service. In the period before the last world war, European civil servants in the Gold Coast received an average of £40 per month, with quarters and other privileges. Africans got an average salary of £4.

There were instances where one European in an establishment earned as much as his twenty-five African assistants put together. Outside the civil service, Africans obtained work in building projects, in mines and as domestics – all low-paying jobs. It was exploitation without responsibility and without redress. In 1934, forty-one Africans were killed in a gold mine disaster in the Gold Coast, and the capitalist company offered only £3 to the dependants of each of these men as compensation.

Where European settlers were found in considerable numbers, the wage differential was readily perceived. In North Africa, the wages of Moroccans and Algerians were from 16% to 25% those of Europeans. In East Africa, the position was much worse, notably in Kenya and Tanganyika. A comparison with white settler earnings and standards brings out by sharp contrast how incredibly low African wages were.

While Lord Delamere controlled 100,000 acres of Kenya’s land, the Kenyan had to carry a kipande pass in his own country to beg for a wage of 15/- or 20/- per month. The absolute limit of brutal exploitation was found in the Southern parts of the continent; and in Southern Rhodesia, for example, agricultural labourers rarely received more than 15/- per month. Workers in mines got a little more if they were semi-skilled, but they also had more intolerable working conditions.

Unskilled labourers in the mines of Northern Rhodesia often got as little as 7/- per month. A lorry-driver on the famous copper-belt was in a semi-skilled grade. In one mine, Europeans performed that job for £30 per month, while in another, Africans did it for £3 per month.

In all colonial territories, wages were reduced during the period of crisis which shook the capitalist world during the 1930s, and they were not restored or increased until after the last capitalist world war. In Southern Rhodesia in 1949, Africans employed in municipal areas were awarded minimum wages from 35/- to 75/- per month. That was a considerable improvement over previous years, but white workers (on the job for 8 hours per day compared to the Africans’ 10 or 14 hours) received a minimum wage of 20/- per day plus free quarters, etc.

The Rhodesians offered a miniature version of South Africa’s apartheid system, which oppressed the largest industrial working class on the continent. In the Union of South Africa, African labourers worked deep underground, under inhuman conditions which would not have been tolerated by miners in Europe.

Consequently, black South African workers recovered gold from deposits which elsewhere would be regarded as non-commercial. And yet it is the white section of the working class which received whatever benefits were available in terms of wages and salaries. Officials have admitted that the mining companies could pay whites higher than miners in any other part of the world because of the super profits made by paying black workers a mere pittance.* [*As is well known, those conditions still operate. However, this chapter presents matters in the past tense to picture the colonial epoch.]

In the final analysis, the shareholders of the mining companies were the ones who benefited most of all. They remained in Europe and North America and collected fabulous dividends every year from the gold, diamonds, manganese, uranium, etc. which were brought out of the South African sub-soil by African labour. For years, the capitalist press itself praised Southern Africa as an investment outlet returning super profits on capital invested.

From the very beginning of the Scramble for Africa, huge fortunes were made from gold and diamonds in Southern Africa by people like Cecil Rhodes. In the present century, both the investment and the outflow of surplus have increased. Investment was mainly concentrated in mining and finance where the profits were greatest.

In the mid-1950s, British investments in South Africa were estimated at £860 million and yielded a stable profit of 15% or £129 million every year. Most mining companies had returns well above that average. DeBeers Consolidated Mines made a profit that was both phenomenal and consistently high – between $26 million and $29 million throughout the 1950s.

The complex of Southern African mining concerns operated not just in South Africa itself, but also in South West Africa, Angola, Mozambique, Northern Rhodesia, Southern Rhodesia and the Congo. Congo was consistently a source of immense wealth for Europe, because from the time of colonisation until 1906, King Leopold of Belgium made at least $20 million from rubber and ivory.

The period of mineral exploitation started quite early, and then gained momentum after political control passed from King Leopold to the Belgium state in 1908. Total foreign capital inflow into the Congo between 1887 and 1953 was estimated by the Belgians to have been £5,700 million. The value of the outflow in the same period was said to have been £4,300 million, exclusive of profits retained within the Congo.

As was true everywhere else on the continent, the expatriation of surplus from Congo increased as the colonial period wore on. In the five years preceding independence the net outflow of capital from Congo to Belgium reached massive proportions. Most of the expatriation of surplus was handled by a major European finance monopoly, the Societé Generale.

The Societé Generale had as its most important subsidiary the Union Miniére de Haute Katanga, which has monopolised Congolese copper production since 1889 (when it was known as the Compagnie de Katanga). Union Miniére has been known to make a profit of £27 million in a single year.

It is no wonder that of the total wealth produced in Congo in any given year during the colonial period, more than one-third went out in the form of profits for big business and salaries for their expatriate staffs. But the comparable figure for Northern Rhodesia under the British was one half.

In Katanga, Union Miniére at least had a reputation for leaving some of the profits behind in the form of things like housing and maternity services for African workers. The Rhodesian Copper Belt Companies expatriated profits without compunction.

It should not be forgotten that outside of Southern Africa, there were also significant mining operations during the colonial period. In North Africa, foreign capital exploited natural resources of phosphates, oil, lead, zinc, manganese and iron ore. In Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, there were important workings of gold, diamonds, iron ore and bauxite. To all that should be added the tin of Nigeria, the gold and manganese of Ghana, the gold and diamonds of Tanganyika, and the copper of Uganda and Congo-Brazzaville.

In each case, an understanding of the situation must begin with an enquiry into the degree of exploitation of African resources and labour, and then must proceed to follow the surplus to its destination outside of Africa – into the bank accounts of the capitalists who control the majority shares in the huge multi-national mining combines.

The African working class produced a less spectacular surplus for export with regard to companies engaged in agriculture. Agricultural plantations were widespread in North, East and South Africa; and they also appeared in West Africa to a lesser extent. Their profits depended on the incredibly low wages and harsh working conditions imposed on African agricultural labourers and on the fact that they invested very little capital in obtaining the land, which was robbed whole-sale from Africans by colonial powers and then sold to whites at nominal prices.

For instance, after the Kenya highlands had been declared ‘Crown Land’, the British handed over to Lord Delamere 100,000 acres of the best land at a cost of penny per acre. Lord Francis Scott purchased 350,000 acres, the East African Estates Ltd. got another 350,000 acres, and the East African Syndicate took 100,000 acres adjoining Lord Delamere’s estate – all at giveaway prices. Needless to say, such plantations made huge profits, even if the rate was lower than in a South African gold mine or an Angolan diamond mine.

During the colonial era, Liberia was supposedly independent; but to all intents and purposes, it was a colony of the U.S.A. In 1926, the Firestone Rubber Company of the U.S.A. was able to acquire one million acres of forest land in Liberia at a cost of 6 cents per acre and 1% of the value of the exported rubber. Because of the demand for and the strategic importance of rubber, Firestone’s profits from Liberia’s land and labour carried them to 25th position among the giant companies of the U.S.A.

No comments:

Post a Comment