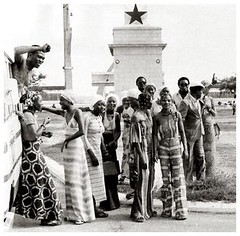

Fela in Ghana during the 1970s. His life and legacy is being portrayed on Broadway with a musical play. Fela joined the ancestors in 1997.

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire File Photos

Feeling Unsettled at a Feel-Good Show

By CHARLES ISHERWOOD

New York Times

“I KNOW there is nothing a white person can say to a black person about race which is not both incorrect and offensive,” James Spader’s hard-driving lawyer says in the new David Mamet play, “Race.” “I know that. Race is the most incendiary topic in our history. And the moment it comes out, you cannot close the lid on that box. That may change. But not for a long long while.”

That harsh sentiment, a classic bit of Mametian blunt speak, might earn a particularly sympathetic hearing from the friends of the Senate majority leader, Harry Reid. As much as we would like to think we live in a postracial America, having elected a black president, the potency of race as a topic for generating scandal — however cynical or bogus — suggests otherwise.

This partly explains why I’ve been finding plenty of reasons to put off airing my conflicted reactions to the new musical "Fela!" Mr. Mamet’s drama, about a legal case that ostensibly turns on perceptions of racism, seems intended to stoke controversy with its forthright title and its boiling arguments about who can say what to whom. But paradoxically the most provocative show in town in this regard may be the feel-good musical about the Nigerian singer and activist Fela Anikulapo-Kuti.

As much as I enjoyed the show, directed and choreographed by Bill T. Jones, it left me with lingering questions about the depiction of the African milieu it evoked. In short, the emphasis in “Fela!” on the spectacle of African culture tilted the show a little too closely toward minstrelsy. It evoked an unsettling feeling I can’t say I ever had before at the theater.

Hold the digital brickbats, please, while I make my case. By definition, of course, “Fela!” has nothing to do with literal minstrelsy, an American form of entertainment dating to the years after the Civil War. Minstrel shows were revues including musical numbers, sketches and jokes performed in blackface (by both blacks and whites, for both blacks and whites) that disseminated ugly racial stereotypes. “Fela!” is about the singer who synthesized various musical influences to invent a new sound called Afrobeat, and who became a galvanizing force behind the Nigerians’ fight against an oppressive and corrupt government. It’s vibrant, exciting and fabulously performed.

But there really are no characters, aside from Fela Kuti himself. True, his mother makes a couple of ghostly appearances and is described lovingly by her son, and during a sojourn in America Fela is shown interacting with a brash woman spouting black-power slogans. (It seems odd that the only character other than Fela Kuti who has any sustained dialogue is an American.) But the rest of the cast members — numbering more than 15 — have no clearly defined roles to play, spending most of the time performing Mr. Jones’s energetic, hip-wiggling riffs on African dance and joining in the songs.

A recent article in The New York Times revealed that the women who represent Fela’s many wives all have researched the back stories of their characters, but in the context of the show we learn virtually nothing about any of them. (You might not even pick up on the fact that they’re supposed to represent his wives.) In contrast with characters in recent plays like Lynn Nottage’s “Ruined” and Danai Gurira’s “Eclipsed” — both of which explore the hard experience of African women by depicting fully developed lives caught in trying, sometimes terrible circumstances — the women of “Fela!” are largely festive window dressing. Attired in eye-catching, vibrantly colored, flesh-baring ensembles, with their faces painted, they strut around the stage and the theater looking exotic, imperious and sexy. So too do the male members of the ensemble, who also bare a lot of flesh but have little to do other than sing and dance.

Hence my discomfort. The presentation of African culture as a feast of exotic pageantry has the potential, at least, to reinforce stereotypes of African people as primitive and unsophisticated, albeit endowed with astounding aptitudes for song and dance. Although some of the dancers have individual moments, none are given individual voices; sometimes they simply drape the stage like gaudy décor. And the way the dancers weave in and out of the audience repeatedly seems ingratiating, a sort of seduction that almost sexualizes the performers.

The fourth wall serves many purposes at the theater, but one is to allow the audience to have some intellectual perspective on the material. In frolicking so exuberantly among the theatergoers, “Fela!” sometimes seems to turn its ostensible characters into flashy sideshow entertainments, to elevate sensation over substance.

The absence of staged narrative that might allow for more richly developed characters partly derives from the way the show is structured. A more evolved kind of jukebox musical, “Fela!” is conceived as a concert taking place on the final night at the Shrine nightclub, where Fela’s fans gathered to party and to hear his political consciousness-raising patter.

The man himself does all the talking, providing snippets of his life history in between the songs and ecstatic dance numbers. But the storytelling is scattered and sometimes indistinct. (You learn more about the sociopolitical situation by reading the newspaper headlines in the video projections on the set.) I suspect that if the show struck a greater balance between pure dance and cogent storytelling — or managed to weave the two together a bit more consistently — my sense that the exotic was being overemphasized (even fetishized) would evaporate.

Context is key here too. Would I feel any discomfort if I were attending an African dance recital at Dance Theater Workshop? Probably not. An air of exuberant commercialism surrounds Broadway productions — you can buy $20 “Fela!” programs and T-shirts at the theater — that can sometimes add a surface layer of crassness to shows that are intrinsically free from it. Fine art can be cheapened by the need to compete in a commercial marketplace. The carnivalesque atmosphere at “Fela!” is more pronounced on Broadway than it was in the show’s earlier run Off Broadway. The theater is bedecked in vibrantly colored panels of corrugated metal and African gewgaws; the intention is to immerse the audience in a sense of being at the Shrine, but it is unintentionally a little like being in a Disneyland version of Africa.

And this parade of African experience is being staged for Broadway audiences who are still largely white, middle aged and middle class. (At the performances I’ve attended the audience looked to be about 60 percent to 70 percent white, which is nevertheless significantly smaller than at most Broadway shows.) Many will have had little exposure to African culture, and some may come away with the impression that the partying played a larger role in the lives of the people surrounding Fela than the grim political battles and the economic hardship. (For obvious reasons Fela Kuti cannot announce from the stage that he had AIDS and died in 1997.)

To be sure, the climax of the show describes in grim, harrowing detail the death of his mother and the horrific abuse of his wives during a government raid on his compound. Mr. Jones and Jim Lewis, who together wrote the book, have done their best to include as much pertinent history as the concept for the show can comfortably allow. The signal truth of Fela Kuti’s life is that his music was the vehicle for his political activism; the two cannot be separated. It’s for those in the audience — and I encourage everyone with an interest in new currents in theater to attend — to decide for themselves how effectively “Fela!” strikes a balance between presenting African experience as an audience-seducing entertainment and revealing the turbulent complexities of the culture behind it.

No comments:

Post a Comment