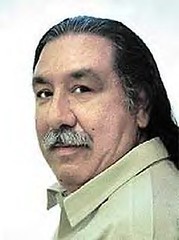

Leonard Peltier, a Native American political prisoner, who was illegally extradited from Canada to the United States. He has been incarcerated for over 30 years. He was recently denied parole until 2024.

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire File Photos

Elsa Claro

Courtesy of Granma International

TWO hundred years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court’s chief justice, John Marshall, ruled that the legal relationship of the land’s original inhabitants with the United States was not one of equals, but of "wardship," given that it dealt with people "completely lacking in civil abilities."

When one native American said "Our work consists of procuring that those who come afterwards, the generations that have not yet been born, do not find a world worse than ours, but instead a better one…" he was focusing on what today is a serious problem stemming from foolish ambitions and the absence of an attitude of consternation regarding the planet. The idea is adjusted to other precepts, including the resentments unleashed among nations and destructive wars to dominate or steal the territory and resources of others.

"Why do they take away by force what they can obtain with love? We are disarmed and ready to give them what they ask if they come as friends…" The idea seems so logical, basic and noble that not to proceed in that manner reveals a lack of moral authority, but the leaders of the United States during its first expansion did not ponder on such advanced possibilities, and acted the way in which they still do today: dispossessing those who were already there when they arrived, and subjecting them to the use of force or imbuing them with pessimism and impotence.

The usurpation of the northern part of this continent could have been less degrading, even though it would always remain an unjust act, in violation of every law. It is difficult to believe, but in the 19th century, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that Indians were, by birth, "alien and dependent." That is one of the reasons that it was included in the Constitution that indigenous peoples could not be represented in Congress.

The nascent empire wanted to expand its geographical horizons and possess those places where there were resources to explore. That is also the source of the barbaric statement by Philip Sheridan: "The only good Indian is a dead Indian."

Whoever assumes that these are questions of the past is ignoring or giving short shrift to the racial discrimination that African Americans continue to suffer after so many projects with little progress, after years of struggle and the deaths of so many civil rights fighters. It is the same case, with its own particularities, of the Native Americans who live on reservations — like the Bantustans of South Africa — often on highly toxic land, and are insulted, ignored or questioned when they want to maintain their customs.

"We do not have control over the resources on our reservation; we do not have economic power…. That is why a major controversy persists in the state of South Dakota about the problems and double standards of justice (one for "whites" and another for Indians) that we protested in the 1960s and ‘70s."

— Excerpt from an interview with Leonard Peltier by German political scientist Heinz Dietrich.

Peltier is one of the longest-held prisoners in the United States, treated like one of the many "bad Indians" typically stereotyped in those "Western" flicks with which they made us believe and "demonstrated" the superiority of the criminals and the absence of virtue among the abused, who today continue to be the system’s evident victims.

THE PELTIER CASE

The FBI still has some 100,000 pages of secret information on Peltier. Independent investigations and those by international agencies, however, place the story of this Anishinabe/Lakota man in the 1970s — dubbed the "prodigious decade" by some because it gave the world significant changes in music and considerably broad social movements, including the anti-Vietnam War movement.

Peltier was part of the American Indian Movement (AIM), a group committed to the progress of indigenous communities, based on the preservation of cultural pride. They were joined by the so-called traditionalists, tribes determined to maintain their customs, moral sovereignty and closeness to nature.

Those expressions of emancipation were never smiled upon [by the U.S. authorities]. Several members of these communities were killed, and after suffering various abuses, they held a protest in 1973 in the town of Wounded Knee, on the Pine Ridge reservation. They were savagely repressed, and although the government promised to investigate complaints filed by the victims, the reservation’s conditions became worse, to the extent that the two protesting groups were unable to enact their ancestral ceremonies together.

In the three years that followed, AIM members experienced many attacks, including their houses being burned down, and were the targets of shots fired from moving vehicles. They were injured or murdered. A campaign against them was organized depicting them as violent, lawless individuals in order to justify the attacks perpetrated by paramilitary forces with the consent of the FBI. According to diverse sources, at the time, it was the FBI that headed the fabrication of a fraudulent scheme to justify any action against these indigenous individuals.

The growth of such a heavy, artificial environment led the traditionalists to call on the AIM activists to return to their reservations and protect them from constant, often deadly attacks. Those who responded to that plea for help included Leonard Peltier, who together with 12 others, camped out on the Jumping Bull Ranch, where a number of families were living. That’s where he was on June 26, 1975, when two FBI agents burst onto the scene in unmarked vehicles. They claimed they were following an Indian who had participated in an assault and robbery.

Residents and police were soon involved in a shoot-out. The police asked for backup from special troops of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. They surrounded the farm, but Peltier was able to get a group of adolescents out to a safe place under the crossfire, which ended up wounding the two FBI agents. Peltier was accused of having finished them off as they lay injured.

Immediately, three AIM leaders were blamed for this outcome: Dino Butler, Bob Robideau, and Leonard Peltier, along with Jimmy Eagle). Butler and Robideau were found innocent by the jury for having acted in self-defense, admitting that the atmosphere of alarm and unease prevailing on Pine Ridge explained why they would have shot back at police fire.

The FBI’s reaction to this verdict was rage, and it withdrew charges against Jimmy Eagle (the man originally pursued by the FBI agents) so that the "full prosecutive weight of the Federal Government could be directed against Leonard Peltier," according to memoranda that were accidentally leaked. This means they were capable of releasing from all guilt the individual who may have been, consciously or not, the trigger of these events, in order to transfer their complete revenge to the man who was a very prestigious and popular activist for his people. In order to guarantee the outcome they finally obtained, they ensured that Peltier was tried by a different judge than his comrades, one who stood out for the rigidity of his considerations.

Peltier was extremely dubious about the quality of the trial to which he was to be subjected, based on the highly prejudiced approach and zeal for vendetta that was in the air in the region. He traveled to Canada, where he was arrested some months later. In order to extradite him to the United States, testimony against him was presented from a woman who despite not knowing him, claimed that she was his girlfriend and that she saw him shoot at the agents. She was not even present at the site during those events, and later retracted her statement, saying that her false testimony was given under threat and pressure from the FBI.

In any case, Peltier was extradited, and a rigged trial took place in the United States (Fargo, North Dakota, 1977), after which Peltier was sentenced to a double life term in prison, despite expert testimony that the bullets that killed the two agents were not fired from his gun.

According to Amnesty International, "after studying the case in depth for many years… different aspects continue to be of concern regarding the impartiality of the proceedings that led to his conviction, such as the evidence linking him to the point-blank shooting and the coercion of an alleged eyewitness."

Along with about 50 U.S. congress members and several members of the Canadian Parliament, Amnesty International joined with other groups demanding a new trial for Peltier, this time an impartial one, given that it is clear that the defendant suffered manipulation in the case brought against him for his extradition in 1976, for which the prosecution has retained "potentially key" ballistic evidence that "could have helped defend Leonard Peltier."

A SCAPEGOAT?

Some hold that Peltier served as an element of contention against a movement that was taking shape and becoming strong at a time when the government thought it had squelched all indigenous attempts at demanding their rights. The government was particularly desirous of putting a stop to indigenous resistance because of the development of mega-energy projects on lands allocated to tribes via signed treaties.

A large number of the treaties reached with tribal chiefs — when a fatally dissolute level of decorum still existed — were broken at different times and in their overwhelming majority. By the time the abovementioned events occurred, the idea was to repeat these violations of promises made, but it encountered the opposition of new generations united with their elders, convinced that living in harmony with nature was better than destroying it, and considering that there was no reason to cede on rights that had already been considerably diminished, and that it was preferable to defend them no matter what the cost.

Over time, it has been learned that the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota was in reality selected for a "peacekeeping" paramilitary operation by the FBI, which would have taken all of the counterinsurgency war methods it has implemented in various countries, to apply them against nonconformist Indians at a time when various protest movements of oppressed minorities were converging in the country, standing up for their rights.

By the mid-1970s, some 60 members of the AIM or its followers had been killed. Given that the previous "warnings" carried out did not have the desired results, they went on to escalate the attacks and injustice. The context of violence was of such magnitude that the leaders and elders of the Oglala tribe created the Jumping Bull encampment — where the fatal events later occurred — to protect their families from the deadly police and paramilitary operations.

The fact that the people were capable of organizing and resisting was intolerable to the "white authorities," who sought a pretext and a scapegoat to put a stop to indigenous attempts at resistance. They had Peltier in their sights because of his popularity. Later, he became the right man to be used in their plan of containment. Asked why he had not been given another trial, he said, "They know that if I get a new trial, they have a snowball’s chance in hell of winning."

Before his case was sent to the Federal Parole Commission, he was beaten in jail, as a way of trying to dampen his activism in prison for noble causes. It was also meant to lay the bases for putting him in solitary confinement, alleging that he was centrally responsible for the disorder, and depicting him as an inveterate rebel after three decades of attempting to wear him down. That was how he was to appear before the board that was to evaluate him, in a position that was not at all advantageous.

In July 2009 he was assessed for parole, always denied. His lawyer spoke in favor of parole, citing his good conduct and the promise of the Turtle Mountain tribe to take him into their fold.

The parole denial was based on the idea that releasing him would "disregard the seriousness of his offenses and would promote disrespect for the law." The commission ignored the fact that one of the former defendants had admitted shortly before that he had fired the shots that killed the agents.

This means that not even the conclusive evidence of that spontaneous confession was enough for those who used and maintain the opinion that they are making an "example" out of him, so that others do not dare to be defiant again.

It is shameful to know that Peltier’s next parole hearing is in 14 (!) years. The commissioners know that Peltier is suffering from several serious conditions, and is receiving poor medical attention, meaning they could become worse or even cause his death while incarcerated.

Prominent individuals from the arts, the law and politics, as well as ordinary citizens from many countries, are demanding clemency for such a glaringly twisted case, taken to an extreme of notorious perversity.

At this time, a letter to Barack Obama is circulating with the request that Peltier’s case be reviewed, or freedom should be given to a man who never should have been subject to such a prolonged and illegal sentence. There are no great hopes that this president, among all the others who were similarly petitioned, will be the one to absolve him.

No comments:

Post a Comment