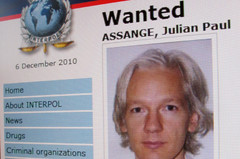

An INTERPOL wanted poster for Julian Assange who was arrested by the British police on December 7, 2010. The WikiLeaks website has exposed U.S. war crimes and other political intrigue carried out by the world's leading imperialist state.

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire File Photos

Tuesday, 04 January 2011 00:00

Eluem Emeka Izeze Managing Director/Editor-in-Chief

Nigeria Guardian

THE art of keeping secrets has always been the necessary outcome of a human society where nations and men seek to outwit each other in an endless race to gain advantage. In fact seeking to safeguard secrets has through the ages developed into a process through which the simple activity of human interaction is mystified and turned into a complex web of intrigues.

Governments go to great length to keep out of public glare, even mundane issues that could at best only serve as mild embarrassments, if made public. But that was before the world changed recently with the launch of a website, curiously named, wikileaks.

It’s founder, Australian-born Julian Assange, seemed committed to exposing all that powerful governments around the world seem intent on hiding from the public. Not long ago, it began publishing a treasure throve of information emanating from the United States government, it was essentially made up of dispatches from American diplomatic missions around the world.

Striped of all facade, it showed in bold relief what American officials really think of nations of the world and their leaders. This was an unprecedented event and sent alarm signals around the world that secrets may no longer be secrets as they were known.

It was probably an inadvertent action that has now begun the process of redefining relations among nations in particular, and in some measure, the way governments are run. Nothing is sacrosanct any more, not even from the most powerful nation in the world. What is secret today, could turn into an open scandal tomorrow.

By his actions, therefore, Mr. Assange seems to have raised the bar for public accountability among nations, and probably within individual governments. Officials now know that in an information age driven by technology, their opinions and decisions may sooner rather than later surface in the public space.

He seems also to have redefined the word secret, and opened up for good, the murky world of bureaucracies, to the public for critical examination. These are momentous developments which are striping governments of their exclusive preserves, and handing to citizens, the function of determining the nature and scope of government activities.

Mr. Assange has become controversial by his very actions which have broken new grounds, and which will ensure that governments may no longer function the way we knew them, nor should nations take for granted that their assessment and actions against other nations would be hidden for ever.

It is for these reasons that, in a year of sparse ground breaking events, Mr. Julian Assange has been adjudged by The Guardian Editorial Board to be the Man of the Year 2010. His sometimes startling story is told by Dr. Reuben Abati, Chairman of the

Editorial Board.

Eluem Emeka Izeze

Managing Director/Editor-in-Chief

Julian Assange: WikiLeaks, whistleblowing and the open society ideal

By Reuben Abati

JULIAN Assange spent New Year Day, 2010 in a Norfolk mansion in England, made available for his use, by Vaughan Smith, the avid free speech campaigner; he is on police bail, wears an electronic band to monitor his movement; he is wanted in Sweden for five sex-crime allegations including a case in which he is accused of having nonconsensual sex with a woman with whom he had previously had consensual sex, and the second in which he is accused of lying on a female lover who was sleeping naked beside him, “holding her down with his weight and pushing himself into her body” while she was in a “helpless state.”

The rape charges by the Swedish authorities have suddenly become an albatross that Assange’s lawyers are struggling to shake off: they are fighting extradition charges against their client even as they are determined to prove his innocence and secure his freedom.

But this is not what defines this 39-year old who in 2010, through the internet publication of sensitive information forced nations and the entire world to take a second look at themselves, the hegemonic value of information has been well advertised in the process; certain habits in many corridors of power are bound to change after the WikiLeaks phenomenon.

The sex-crime allegations which appeared to have been rested in September 2010, became a fresh and hot issue, with the Swedish branch of Interpol issuing an arrest warrant for Assange, following the November 28, 2010 release by him and his associates, through WikiLeaks, an internet website he founded in 2006, of 251, 000 confidential, secret and classified files on United States’ diplomatic relations with the rest of the world.

Five other media partners joined in the detailed exposure of the rot in high places. Perhaps no other singular act was of such magnitude and impact in 2010, in terms of the furore that it generated and the knowledge that it brought to light.

Assange sees his trial as “politically motivated”, and as pure revenge by those who feel hurt by WikiLeaks’ whistleblowing and Assange’s audacity. He has in more sympathetic quarters become the champion of free speech.

Julian Assange’s travails have resulted in such ideological division across boundaries on such central issues as the freedom of information, national security, human rights and justice, governance and the media, geo-politics and international diplomacy. Only about half of the leaked files have been published so far but the fall-outs have become serious matters of historical curiousity and analysis.

The ultra-conservative wing of the commentariat and policy order, have called Assange an “anarchist, a hi-tech terrorist, a hacker, an enemy of humanity.” The United States State Department accused him of being “reckless and dangerous.” The US Justice Department talked about prosecuting him. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton says he has put lives in jeopardy.

In his native Australia, the authorities are taking a second look at the books to determine under which laws he could be punished; in the meantime there are threats that his Australian passport could be withdrawn!

Contrariwise, he enjoys the support of a global free speech coalition which has held rallies in his defence and placed advertorials in the New York Times and the Washington Post noting that Julian Assange and his WikiLeaks are good for society.

While the jury is still out on the sex-crime allegations, Julian Assange is in the eyes of the ordinary man across boundaries more of a hero than villain, more of a champion than a pest, an achiever and flag-bearer for the open society ideal, not an anarchist, but a progressive. His heroism in this regard raises those pertinent issues that can no longer be ignored, notably the role and method of the whistleblower, the challenge of transparency and accountability in governance and the responsibility of both the media and governments.

The United Nations, one of whose agencies has spoken up in defence of Assange’s rights, considers the freedom of information, as well as access to it, one of the major pillars for building an open and good society. However, despite the existence of Freedom of Information laws in many countries of the world, old habits have remained resilient.

The WikiLeaks publication and the emotional reaction to it, has exposed the continuing hypocrisy of so-called leaders of the civilized world. The reaction by the US authorities for example has been most revealing: the State Department became uncommonly agitated and also engaged in name-calling. The course of history has often been changed by those who force the issues in such a manner that institutions and individuals are compelled to rethink their ways.

The United Kingdom had an Official Secrets Act; “until 1989 even the type of biscuit served to the prime minister was a secret.” South Africa used to be considered one of the freest countries in Africa with regard to information, but in the last two years, the same country has been struggling to curtail press freedom. The battle has been between liberal promoters of free speech, and those who insist that secrecy is required, if government must function effectively, certain things must not be told in the public domain. It is an old, seemingly unending argument.

On November 24, 1643, John Milton had made a strong case for free speech in his essay, Areopagitica. Long before then, in 43 BC., the Roman orator, Cicero was declared an enemy of the state and had his tongue cut off for making the potentates uncomfortable. Likewise, Cinna, the poet of Shakespearean creation, was the target of mob action: “Tear him to pieces for his bad verses” (Shakespeare, Julius Ceasar, Act 3, Sc.3). Power figures have often tried to determine what should be published and what should not in what is considered “the national interest.”

In 1984, The Guardian newspaper (Nigeria) was proscribed and two of its journalists sent to jail, Nduka Irabor and Tunde Thompson, under the obnoxious Decree Four for publishing “state secrets” and refusing to disclose their sources. Newswatch magazine was also later proscribed for six months because the editors dared to publish classified stuff.

Every year, the Committee to Protect Journalists reports cases of assault on journalists all over the world, indicating the intolerance of the authorities. The attack on Julian Assange raises the same question of media repression and censorship, and threat to the lives of whistleblowers.

His critics have described the publications as “indefensible” and there have been calls for his “execution”. Should WikiLeaks have published? Who determines what should be published?

James Madison the architect of the First Amendment to the American Constitution dealing with free speech, says “A people who mean to be their own governors must arm themselves with the power that knowledge gives. A popular government without popular information or the means of acquiring it is but a prologue to a farce or a tragedy or perhaps both.” The assault on Assange is almost farcical if not tragic.

It is not just governments that are after him, certain corporations and organisations including Amazon have withdrawn their support for WikiLeaks, while PayPal, Visa and Mastercard have stopped their customers from donating to it. What is on display is a culture of intolerance even from the most curious quarters including Sweden where existing sunshine laws promote the ideals of an open society.

As a principle, secrecy makes government less accountable to the people, makes it less participatory and encourages impunity. It has been seen in many developing countries and even the First World that public officials and corporations hide information not necessarily for the common good, but selfish, private interests. This is one of the highpoints of the WikiLeaks revelations.

In Nigeria, it is instructive, for example, that the Freedom of Information Bill, initiated in 1999, remains one of the longest pieces of unresolved legislation since Nigeria’s return to democratic rule. Nigeria’s leaders want to continue to function in the dark. Secrecy promotes deception and in corporations it may result in adverse economic effects, and of course it encourages eavesdropping and malicious gossip.

The promotion of openness through whistleblowing, the protection of whistleblowers and a regime of sunshine policy is to be measured with regard to its instrumentality, how it reduces the asymmetry of information relations and encourages accountability. The ENRON scandal and Accenture’s culpability would not have been known were it not for the efforts of whistleblowers.

Bernie Madoff of the Ponzi scheme scandal would still have been walking free if a whistle was not blown. The rot that led to the global economic downturn has been exposed through whistleblowing. The telling caveat provided by Justice Wendell Holmes, however, is that the right to free speech should not extend to “crying fire in a crowded theatre.”

Is this what Julian Assange and WikiLeaks have done: Writing “bad verses” and “shouting fire in a crowded theatre?” The disclosure of sensitive information can indeed have life-threatening implications. But contrary to the US claim that the lives of US operatives may have been endangered, nobody has died because of the WikiLeaks leakages.

There is no threat of another World War. And in fact, only about six per cent of the WikiLeaks materials are classified as “secret”. What has really happened is that ordinary people across nations have been empowered with information: their right to know has been defended.

WikiLeaks through the leaked cables exposed the corruption, selfishness and incompetence of politicians, diplomats and organizations, and how so much indecency is perpetrated in the people’s name. The traditional image of public figures as “disciplined”, always well turned out, knowledgeable and trying to save the world has exploded as a myth: these are actually greedy people who are mostly interested in power.

We have seen that authorities everywhere react similarly whenever they feel challenged and this includes the United States, a country that is regarded as the champion of transparency, free speech and accountability.

Through what has been otherwise described as a reportage of diplomatic tittle tattle, we now know the following: Saudi Arabia wanted Iran bombed, Shell planted moles in the Nigerian government, the same Pfizer which was claiming innocence in the damaging drug trials affair in Nigeria was actually working underground to sabotage official investigations; China launched an attack on Google, Pakistan’s intelligence service, the ISI is double-faced; Russia is a Mafia state, North Korea is supporting Myanmar to build a nuclear science programme and the Yemeni leader was prepared to compromise his country’s sovereignty in order to gain a little favour from the United States: an invitation to Washington DC!

More importantly the whole world has been told that American diplomats who often appear so nice, with invitations to dinners and cocktails, do not necessarily respect their hosts and that what they say is to be taken with a pinch of salt for American diplomacy is driven solely by the goals of American exceptionalism.

So damaging have the revelations been for American diplomacy that the US Ambassador to Nigeria, Terence P. McCulley had to issue a statement to reassure Nigerians.

We should not have a problem with the revelations, for in many ways, they mainly confirm what is already known: that international corporations are full of “hitmen”, that diplomats are good at deception, and that governments cannot always be trusted to be well-meaning.

The mixed reactions to the publications should also be understandable: the Israeli Prime Minister has opined that leaders should learn to “speak in public like they do in private;” in Russia, there is no outrage over the description of Russia as a Mafia state that is controlled by rogues.

But back to Justice Wendell Holmes: the critical point, to be stressed again and again even as the Wikileaks impact is celebrated, is that the people’s right to know and the exercise of power in that regard must be done responsibly.

What kind of information is good for the public? Was Assange selective? Why did he target the United States? Is there blackmail involved or vendetta of sorts? Should everything be in the open? Is some degree of secrecy not required for even in Sweden, which is considered the freest information society, secrecy is maintained with regard to national security and there are similar clauses in Freedom of Information Laws? And are there privacy laws that have been breached?

Julian Assange has offered a defence in so many words: “We keep secret the identity of our sources as an example (and) take great pains to do it. So secrecy is important for many things but shouldn’t be used to cover up abuses, which leads us to the question of who decides and who is responsible…And it is our responsibility to bring matters to the public.” And when WikiLeaks does, what is the motive? Does it consider such issues as peace and security? Julian Assange says he is interested in change and greater efficiency, and here lies the instrumentality of running a website that is a conduit for whistleblowing.

“To me,” he says “organizations can either be efficient, open and honest, or they can be closed, conspiratorial and inefficient.”

This Open society idealism however, is to be measured against the responses from the affected parties. It may serve as a wake-up call for the authorities, but it may also drive them underground and make them more defensive. Perhaps all of this would change the way information is kept by governments and their agencies. In Kenya, John Githongo’s whistleblowing (well documented in Michela Wrong’s It’s Our Turn to Eat, HarperCollins, 2009) has not necessarily resulted in the change of habit that Assange seeks.

In the United States, the State Department and the Department of Defense are more interested in how to prevent a recurrence. Would this take the form of less documentation? Maybe.

For in an information age, with the increasing predominance of the electronic frontier, and the easy and instant globalization of everything including data, there is a near-absolute limit to which the leakage of information can be prevented, especially with so many people involved in the information management process, who are invariably also trapped in Walter Benjamin’s “age of electronic reproduceability.” Where anything can be reproduced electronically, the circumference of control and censorship is clearly defined: this is one of the lessons of the WikiLeaks revolution.

But in the long run, the fear is that the Wikileaks phenomenon may be counter-productive; the revolution that is planned may be subverted by its own methods. This is the disturbing paradox that should be further considered.

For now there is the following good news: In the wake of the revelations beginning November 28, 2010, attempts had been made to shut down the WikiLeaks website, but this was practically impossible as the website also had five other media partners including The New York Times and The Guardian (UK), as well as blogs and social media which reproduced the material and subjected it to further analysis: the effect of electronic reproduceability!.

The WikiLeaks phenomenon is an apt demonstration of the power of the technological revolution represented by new media. The English authorities had directed that Milton’s treatise on “The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce” should be burned because it was not registered by the censors, even his Areopagitica was unlicensed, many books have been banned or burned all through history but the metaphor of the computer allows much greater freedom that checks the tactics of repression. Also on display was Julian Assange’s determination and faith.

Born on 3 July 1971 in Australia, he is a child of the internet age and one of its emergent apostles, a product of the post-modernist season and a poster male for the reconstruction of public intellectualism. He is an internet activist, a software developer, computer programmer, a one-time, computer hacker (for fun), a self confessed cynic and “subversive” who wants to change the world by exposing hypocrisy and abuses in high places.

The cybernetic state has empowered his kind and his generation in hitherto unimaginable ways, creating new levels of awareness on a global scale. It is particularly instructive that in the present debacle, the old media found itself depending on WikiLeaks for prime stuff. The old media is constrained in ways in which the new media dominated by citizen journalists is not, and thus the electronic frontier reshapes the frontiers of human freedom and consumer choices with the additional advantage of interactivity. The cybernetic state is also for the most part the liberal state, except may be in China and Russia.

It is noteworthy also that the example of Julian Assange and WikiLeaks has inspired many imitation WikiLeaks on the internet.

Such sites for all their drama and instrumentality are often open to abuses though, and can be used as platforms for blackmail and extortion and for “crying fire in a crowded theatre.” There are both ethical and moral issues with the use of the internet therefore, and so an old principle becomes applicable: Quis custodiet iposes custodies (who will guard the guards?”). Assange has boasted of WikiLeaks’ “four years of publishing history…” But is it the truth and nothing but the truth? Some of the staff who walked away from WikiLeaks have protested that the website does not run a transparent system. Assange himself in another instance has complained about how blogs and social media sites can be used by commentators expressing an opinion, not to state the truth but to reposition themselves among their peers in examining a topical subject.

Judith Miller in criticizing Assange says he is a “bad journalist”. Why? “Because he didn’t care at all about attempting to verify the information that he was putting out or determine whether or not it hurts anyone.” Sarah Palin insists that he is not even a “journalist.”

Allegations such as this are made even after Assange has addressed them; he does not describe himself as a journalist, but as editor-in-chief of WikiLeaks and its spokesperson. But where is the difference?

In the globalized age of technology, old definitions continue to prove inadequate. It is difficult to predict the outcome of Assange’s rape cases, and we need not do so, but that his WikiLeaks has made tremendous impact for good or ill, depending on where you stand in the court of public opinion, is not in doubt. And the lessons are many: that there are serious issues of morality in international diplomacy; that governments need to reconsider what is secret, and what is not, as well as their management of information processes, that nothing may be hidden forever in the age of technology, the freedom of information and the open society ideal are not without their discontents, and that the new media is a an emergent hegemony whose influence would reach far into the future. For being the lighting rod for a reassessment of all of these and for the sheer, transformative impact of WikiLeaks in 2010, Julian Assange is our Man of the Year.

No comments:

Post a Comment