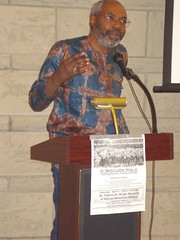

Abayomi Azikiwe, editor of the Pan-African News Wire, speaking at the Dr. Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History on April 5, 2008. The event commemorated the 40th anniversary of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire File Photos

What will the army, police and its components do in a crisis for a neo-colonial state?

By Abayomi Azikiwe

Editor, Pan-African News Wire

Feb. 9, 2011 in Egypt witnessed the working class taking center stage again at the appropriate period and with proper emphasis on key sectors of the economy and the governmental apparatus. Trade unions in Egypt, who have escalated their efforts of the last several years in demands for economic and political rights, engaged in a general strike that further paralyzed the economy that was reeling after three weeks of popular uprisings throughout the North African country of 80 million people.

Vice-President Omar Suleiman, who according to a recent commentary on Al Jazeera, is the United States Central Intelligence Agency’s main man in Egypt, had become the most visible figure to the international community. Suleiman has close ties with the U.S. security and intelligence apparatus which utilized the Mubarak regime to engage in military operations involving kidnapping, interrogation and torture.

Suleiman announced on Feb. 8 that if the general strikes and mass demonstrations did not end in Egypt that there would be a military coup in the country. On Feb. 10, there was much speculation that Mubarak would resign from office with either a Suleiman caretaker government or a military coup inheriting the political crisis. The defense minister Tantawi was quoted in the media as saying that “the military would guarantee the people’s rights.”

Most people interviewed over Al Jazeera stated that the removal of Mubarak was only the first demand. The people do not want to merely replace Mubarak with Suleiman and Tantawi, or any other unrepresentative and repressive figures, that the workers, farmers and youth want the entire ruling National Democratic Party (NDP) removed from the reins of power in Egypt.

In a Press TV report of Feb. 14, it stated that “Egypt’s military has rejected the demands of pro-democracy protesters for a swift transfer of power to a civilian administration, saying it will rule by martial law until presidential elections are held in September.”

This same report continues by noting that “The army’s announcement, which included suspension of the Egyptian constitution, was a further rebuff to some pro-democracy activists after troops were sent to clear demonstrators from Cairo’s Liberation Square, the center of the protests that brought down President Hosni Mubarak.”

Press TV quoted the head of the military police, Moustafa Ali, as saying that “We do not want any protesters to sit in the square after today” and issued a communique indicating that it would crack down on those creating “chaos and disorder” and that the military would ban further strikes by trade unions and students.

Class Character of the Military in Africa

With the advent of colonialism, the European powers established armies and police units to serve as a buffer between the ruling class and the African masses of farmers and workers. The officers and the rank-and-file military and police personnel were often trained by the colonial forces and imbued with their ideological orientation.

In many instances the military leaders, who worked underneath the colonial rulers who were the real commanders of the police and army, were sent abroad for training. Consequently, most of them treated the national liberation movements with hostility and saw their principal role as defending the colonial system from the majority of the population who had no vested interests in the status quo.

According to Kwame Nkrumah, the first leader of the Republic of Ghana and a revolutionary socialist, “The majority of Africa’s armed forces and police came into existence as part of the colonial coercive apparatus. Few of their members joined the national liberation struggles. For the most part, they were employed to perform police operations against it.” (Class Struggle in Africa, p. 41)

Nkrumah goes on to assert that “In many cases, the officer class and the civil servants have shared similar educational experience in elite schools and colleges in Africa and overseas. They have developed similar outlooks and interests. They tend to distrust change, and to worship the organizations and institutions of capitalist bourgeois society.” (Class Struggle in Africa, p. 42)

Nonetheless the military in Africa is also divided along class lines. Nkrumah notes that “The rank and file of army and police are from the peasantry. A large number are illiterate. They have been taught to obey orders without question, and have become tools of bourgeois capitalist interests. They are alienated from the peasant-worker struggle to which through their class origins they really belong.” (Class Struggle in Africa, p. 43)

Consequently, the rank and file soldiers and police can easily become pawns in the system of neo-colonialism and imperialism. Such a set of social circumstances “means that the rank and file soldier or policeman can be used to bring about, and to maintain, reactionary regimes. In this, the ordinary soldier who is after all only a worker or peasant in uniform, is acting against the interests of his own class.” (Class Struggle in Africa, p. 43)

However, there have been examples in the history of African and Arab states when the lower ranking military officers have played a progressive role. In 1952, the Free Officers Movement overthrew the monarchy in Egypt claiming that King Farouk and higher ranking officers in the military were corrupt and largely responsible for the defeat of the country in the 1948 war against Israel.

The Free Officers Movement, which was led by a lower ranking military officer, Lt. Col. Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein, along with Gen. Muhammad Naguib, who served as the figured head of the July 23 Revolution until 1954, when Nasser would assume full control, set out to establish Egypt as a republic. Under Nasser, the British and French controlled Suez Canal was nationalized in 1956 leading to a brief war with Israel, London and Paris.

Nasser’s role in mobilizing the people of Egypt and playing off the United States against France and Britain resulted in the North African state prevailing in the war. Later Egypt under Nasser would become a major force in Pan-Arab and Pan-African nationalism and socialism. Nasser would also be a co-founder of the Non-Aligned Movement along with Nkrumah of Ghana, Tito of Yugoslavia, Nehru of India and Sukarno of Indonesia in 1961.

During the early 1960s, Egypt under Nasser hosted hundreds of members of national liberation movements from territories still under colonial rule in Africa. At this at time Egypt made a conscious political decision in conjunction with Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana and other Pan-African and anti-imperialist states to break down the colonialist imposed divisions between northern and sub-Saharan Africa.

Egypt was a co-founder of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1963 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. When the OAU convened at is second annual summit in Cairo in 1964, the issue of whether the organization would take a militant stance in relation to political and economic integration, the struggle against the remaining colonial regimes and the organization’s relationship to the world community, was paramount in the proceedings.

Kwame Nkrumah stated during his address at the OAU summit in Cairo in 1964 that “I am not arguing that we should cut off all economic relationships with countries outside of Africa. I am not saying that we should spurn foreign trade and reject foreign investment. What I am saying is that we should get together, think together, plan together and organize our African economy as a unit, and negotiate our overseas economic relations as part of our general continental economic planning. Only in this way can we negotiate economic arrangements on terms fair to ourselves.” (OAU speech 1964 taken from Revolutionary Path, 1973)

It is also significant that at the OAU 1964 Cairo summit Malcolm X (El Hajj Malik Shabazz) presented an eight-page memorandum to the heads of state asking for their support in the struggle of people of African descent in America. Placing the plight of African Americans within the context of the international struggle against imperialism and colonialism, Malcolm laid the basis for the emergence of modern-day Pan-Africanism in the West.

Malcolm stated in Cairo that his newly-formed group “The Organization of Afro American Unity (OAAU) has sent me to attend this historic African summit conference as an observer to represent the interests of 22 million African Americans whose human rights are being violated daily by the racism of American imperialists.” (OAAU Statement to the OAU in 1964, reprinted in Malcolm X Speaks)

After the death of Nasser in 1970, Egypt’s progressive domestic and foreign policy began to shift. In the aftermath of the October 1973 Egypt-Israeli war, the new Egyptian leader, Anwar Sadat, moved closer to the United States. Breaking former ties with the Soviet Union and signing a separate peace treaty with Israel, Egypt soon became the largest recipient of U.S. foreign assistance in Africa.

To this day it is still the second largest recipient, next to Israel, of U.S. assistance internationally. The Egyptian security forces and the military have participated in the ongoing suppression of the Palestinian struggle for self-determination and nationhood as well as acting in partnership with U.S. imperialism in its so-called “war on terrorism.”

In other African states such as Somalia in 1969, Ethiopia in 1974 and Burkina Faso in 1983, lower ranking military officers were able to seize power in alliance with popular and revolutionary movements among the civilian populations. Nevertheless, most military coups in Africa have been supportive of the political and economic imperatives of imperialism.

The Need for a Revolutionary Organization

Nkrumah stated that “In the face of the growing awareness of the masses, reactionary governments either attempt to contain it by introducing bogus socialist policies, to suppress it by force, or to carry out a military coup. Whichever method is adopted, they proclaim that they are serving the interests of the people by getting rid of corrupt and inefficient politicians, and that they are putting the economy in order.” (Class Struggle in Africa, p. 54)

The former Ghanaian leader goes on to say of the reactionary civilian and military governments that “They are, in fact, safeguarding capitalism and protecting their own bourgeois interests and the interests of foreign monopoly finance capital.”

According to Nkrumah, whose government was a victim of a reactionary military and police coup backed by the U.S. in 1966, “The rash of military coups in Africa reveals the lack of socialist revolutionary organization, the need for the founding of an all-African vanguard working-class party, and for the creation of an all-African people’s army and militia. Socialist revolutionary struggle, whether in the form of political, economic or military action, can only be ultimately effective if it is organized, and if it has roots in the class struggle of workers and peasants. (Class Struggle in Africa, p. 54)

No comments:

Post a Comment