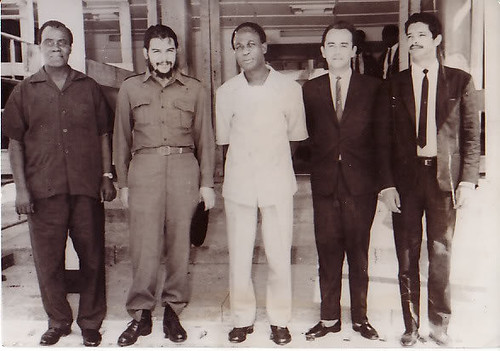

Kojo Botsio, Che Guevara, Kwame Nkrumah and two Cuban officials in Ghana during the Guevara visit in late 1964 and early 1965 when he toured several African states. Guevara would work to liberate Congo in 1965., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

Kwame Nkrumah the Socialist

Nkrumah‘s controversial life and legacy continues to provoke passionate debates amongst Ghanaians to the present day. Nkrumah is both praised for his vision and castigated for it. His vision of a United States of Africa and support for other liberation movements, prompted his critics to accuse him of not spending enough time and resources on his own country. Egotist or visionary?

Nkrumah was fighting not just against colonialism but also against capitalism. Independence from Ghana meant independence from world capitalism and a new society which provided security and justice for all. He believed socialism was compatible with African culture and attempted to apply Western socialist theory in an African context. In a 1967 essay entitled “African Socialism Revisited” he wrote: “We know that the “traditional African society” was founded on principles of egalitarianism…Any meaningful humanism must begin from egalitarianism and must lead to objectively chosen policies for safeguarding and sustaining egalitarianism. Hence, socialism.”

His own style of non-aligned Marxism was too much for the leaders of world capitalism – the USA and the United Kingdom – and they believed that a socialist Ghana would provide the spark to fire up the whole of Africa. They were right to be nervous. Nkrumah’s vision that “the independence of Ghana would be meaningless unless it was tied to the total liberation of Africa.” has similarity to the Trotskyite concept of ‘permanent revolution’.

Seeing a threat to their valuable markets, the US and the UK set about removing the problem. Declassified documents by the British and Americans show the coup against Nkrumah was organised by the CIA with support from the British and executed by Ghanaian collaborators. It was then consolidated by a campaign of misinformation which still lingers on in the minds of the people.

Cold war hypocrisy meant that socialist countries were attacked for lack of democracy and human rights whereas right-wing countries that were dictatorships and brutally murdered people were supported and strengthened. Nkrumah was therefore accused of being undemocratic, a dictator, a thief and a murderer.

Accusations of dictatorship stem from the Marxist idea of the ‘Dictatorship of the Proletariat’. Nkrumah wrote, ‘Even a system based on a democratic constitution may need backing up in the period following independence by emergency measures of a totalitarian kind.’

When the ‘dictatorship of the Bourgeoisie’ is overthrown the new state has to be protected against attack from the old order and their foreign supporters. In particular, the Deportation Act of 1957, allowed the state to expel people whose presence in the country was deemed not in the interest of the public good. The Preventive Detention Act, passed in 1958, gave power to the prime minister to detain people for up to five years without trial. Ironically, the idea behind this later law is now readily accepted by the UK and US governments in their ‘war on terrorism’.

On July 1, 1960, Ghana became a republic, and Nkrumah won the election. Shortly thereafter, Nkrumah was proclaimed president for life, and the CPP became the only party.

The colonial plan was to create a dependency culture. According to a delegate to the French Association of Industry and Agriculture in March 1899, the aim of the colonial power must be:

“to discourage in advance any signs of industrial development in our colonies, to oblige our overseas possessions to look exclusively to the mother country for manufactured products and to fulfil, by force if necessary, their natural function, that of a market reserved by right to the mother country’s industry”.

Nkrumah believed in moving Ghana out of the colonial trade system by reducing its dependence on foreign capital, technology, and material goods. He therefore believed in the rapid industrialisation of the country, much as the Soviet Union had done.

With the luxury of hindsight we can re-evaluate this policy that was widely subscribed to throughout not just the socialist world but the capitalist world also. Urban life is eroding the traditional culture and values of Ghana. Like elsewhere in the world it is impoverishing the people by removing them from the only means of physical, spiritual and emotional well-being – the extended family and community life.

Industrialisation has also contributed to global warming and climate change threatening our very existence. The perhaps naive belief that science and technology will create a new world and transform people can also be reassessed in the light of the experience of the rich countries.

Technology has distanced people whilst claiming to bring them together, it has increased the workload whilst promising more leisure time and has destroyed the delicate balance between humans and the natural world in its attempt to dominate nature and in its belief that the world is imperfect and needs to be improved. It is not a simple solution.

Under socialism it was expected that the role of the trade unions would change. Through the Trade Union Act of 1958 strikes were banned. The new role of the unions was to support the emerging socialist state and not to stand in opposition to it. Nkrumah also believed that strikes were a weapon of the opposition in their attempt to destabilise the new society.

Unfortunately, socialist concepts of sharing came into conflict with the real aspirations of the people. When the world price of cocoa rose from £150 to £450 per ton in 1954, Nkrumah diverted the additional profit to national development rather than allowing the farmers to benefit directly.

The cocoa farmers were furious and Nkrumah fell into disfavour with one of the major constituencies that helped him come to power in the first place.

Numerous assassination attempts and “psychological warfare” by America created a siege mentality which made Nkrumah deeply suspicious and less accessible. His advisors were wary of telling him the truth about the situation in the country in case they were seen as opposing his vision. Without the close supervision of Nkrumah the government and civil service became increasingly corrupt.

On February 21st, 1966, the Ghanaian ambassador to Washington sent an urgent message that Nkrumah should go to Hanoi, the capital of Vietnam. For many months Nkrumah had been working on a peace plan although he had suggested that the peace talks be held in Accra.

Unknown to Nkrumah the organisation of a coup was well under way and the last part of the plan was to get Nkrumah out of the country, as far away as possible. Lt. General Joseph A. Ankrah took power and books on Nkrumah, socialism and communism were burned at the grounds of the Trades Union Congress in Accra.

Ideas are not so easy to burn however. Nkrumah’s vision continues to inspire; his mistakes to educate. Have the lessons been learnt?

No comments:

Post a Comment