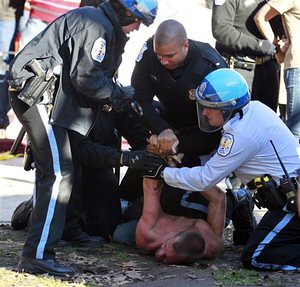

Washington D.C. cops arrest members of the Occupy DC encampment. The attacks follow a similar pattern in many cities throughout the United States., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

Demonstrators affiliated with the Occupy movement faced challenges in several cities, including Charlotte, N.C., and Oakland, Calif.

By Seattle Times news services

WASHINGTON — Demonstrators affiliated with the Occupy movement faced challenges in several cities across the country on Monday.

In Washington, D.C., a deadline from the National Park Service for campers to remove their gear or depart from two downtown parks came and went with no immediate effort by the police to clamp down on the campers during daylight hours.

The scene stood in marked contrast to a violent confrontation 3,000 miles away over the weekend when 400 Occupy protesters in Oakland, Calif., were arrested after tearing down construction barricades. As of Monday afternoon, about 100 protesters remained in custody, according to the Alameda County Sheriff's Office, and 42 were set to be released by the end of the day. The other 58 protesters were being held on more serious misdemeanor or felony charges.

Oakland protesters and city officials blamed each other for the weekend's violence, which left three officers and at least two protesters injured.

The protest culminated in rock- and bottle-throwing and volleys of tear gas from the police, as well as a City Hall break-in that left glass cases smashed, graffiti spray-painted on the walls and, finally, flag burning.

Mayor Jean Quan referred to the vandalism at City Hall, where a case containing a model of Frank Ogawa Plaza was destroyed and a flag was burned outside, as "like a tantrum." Members of the Occupy movement, in turn, decried the actions of the police and said the focus on the damage was misplaced.

"I don't think that Mayor Quan is weighing the big picture — the small amount of destruction caused by these autonomous people that may or may not be part of Occupy Oakland, versus the kind of destruction against the environment, working people and poor people," said Wendy Kenin, 40, a spokeswoman for Occupy Oakland.

Until recently, the Park Service has largely taken a hands-off approach to the Washington camps, because there is a long-established right for protesters to hold vigil in federal parks, including long-term ones, as long as there's no camping, which it defines as, among other things, using park land for sleeping and storing personal possessions.

Occupiers in McPherson Square dragged an enormous blue tarp emblazoned with "Tent of Dreams" over a statue of Civil War Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson at the park's center.

Only a few patrol officers watched from the outskirts of the park, where the enforcement deadline had been posted in recent days. At a nearby encampment, Freedom Plaza, police kept a low profile as well. There were no confrontations during the day; instead, many demonstrators removed their camping equipment and unzipped their tents for police to inspect.

But the agency has increasingly come under criticism for allowing legal vigils to turn into permanent campsites that are not permitted under the law. Pressure on the Park Service has increased along with deteriorating conditions, including a rat infestation in McPherson Square and the discovery of an apparently abandoned infant in a tent.

On Jan. 12, Mayor Vincent Gray, a Democrat, wrote to the Park Service director, Jonathan Jarvis, complaining of "serious concerns" about health and safety problems at the sites and citing a rat problem, worries about illness and hypothermia, and other hazards.

Last week, a subcommittee of the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee held a hearing in which Republicans questioned the Park Service over allowing camping to continue.

"We were under the apparent misapprehension that camping was illegal in McPherson Square, and we look forward to hearing the National Park Service explain the difference between camping and a 24-hour vigil, especially when that 24-hour vigil lasts several months," said South Carolina Rep. Trey Gowdy.

In North Carolina, meanwhile, Charlotte-Mecklenburg police waded into the Occupy Charlotte protest site Monday afternoon, arresting at least seven people and dismantling the campground that the group had established last fall.

Capt. Jeff Estes had given Occupy Charlotte's members "one final warning" to take down their tents and comply with an order he had given for the first time almost eight hours earlier.

Police were acting to comply with a new city ordinance that went into effect at midnight, prohibiting groups from camping on city-owned property.

In preparation for the Sept. 3 Democratic National Convention, the Charlotte City Council on Jan. 23 approved ordinances that give police more power to stop and search people during the convention and to arrest people living or sleeping on public property.

Across the country, cities have been enforcing existing ordinances, or passing new anti-camping rules, to clear out Occupy protesters.

Charlotte has said its changes protect the First Amendment, though the American Civil Liberties Union has said some of the measures go too far, including giving police power to arrest people carrying backpacks or coolers if they believe the items are being used to carry weapons.

Large protests — and some violence — have been common at political conventions, and Charlotte-Mecklenburg police say they are trying to ensure they have enough power to keep people and property safe.

Compiled from The New York Times, The Associated Press and Charlotte Observer

No comments:

Post a Comment