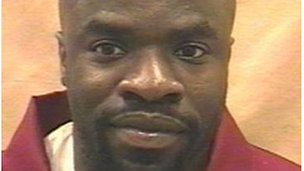

Marcus Reymond Robinson has been saved from death row in a ruling by a judge in North Carolina. The ruling was base on a law against racial discrimination., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

Entrenching racism: the repeal of N.C.’s Racial Justice Act

By Workers World Durham, N.C., bureau on July 27, 2012

North Carolina has a long history of violence and racism, from public hangings at the turn of the 20th century to lynchings and multiple methods of execution, including asphyxiation by gas and death by electrocution. Although the state’s criminal justice system now uses more “sterile” and less public methods of execution, the racist legacy of state-sanctioned murder continues.

The Racial Justice Act, passed in 2009 by the North Carolina General Assembly, was a step toward combating institutionalized racism in the state’s application of the death penalty. The law allowed death-row inmates to present statistical evidence to challenge racial bias in trials where they were tried, convicted and/or sentenced to death. If bias was found in the cases, those sentenced to death would be resentenced to life in prison.

This unique and controversial piece of legislation was an outcome of a 1987 Supreme Court case, McCleskey v. Kemp, in which the court upheld Warren McCleskey’s death sentence by claiming that the statistical evidence of racial discrimination presented on McCleskey’s behalf was not sufficient to demonstrate “deliberate bias” perpetrated by legal officials involved in the case. The Supreme Court claimed this was an issue for policymakers, rather than the courts. Responding to grassroots pressure, the General Assembly enacted the RJA more than 20 years later.

Marcus Robinson was the first defendant to argue on appeal under the RJA this past January. Using statistical evidence, Robinson demonstrated that racial bias was a significant factor in the decision to charge him, in the jury selection and in the court’s sentencing him to death. His case demonstrated undeniable and reprehensible racial discrimination on every level — in the district, county and state courts — and his sentence was remanded to life without the possibility of parole on April 22.

The RJA not only allowed inmates the opportunity to shed light on the racism that resulted in their fates, but it also provided an opening for discussion on a local and national level. The North Carolina Racial Justice Act Research Project at Michigan State University issued a report illuminating the undeniable racist application of the death penalty in North Carolina. (law.msu.edu) The project also analyzed the relevant statistical evidence for Robinson’s case.

Robinson was represented by lawyers from the Center for Death Penalty Litigation, the American Civil Liberties Union’s Capital Punishment Project and attorneys in private practice. This collective representation and use of shared resources allowed the defense to present a formidable case.

However, this level of expertise and resources are not available to the majority of death-penalty prisoners who file appeals. Subsequently Robinson’s case will be the only one heard under the RJA. In a setback to the anti-death-penalty movement, on July 7, the General Assembly gutted the RJA, no longer allowing defendants to use statistical evidence to support claims of racial bias.

However, the loss of the RJA at the hands of the conservative right-wingers has reinvigorated a movement against the racist application of the death penalty and the untenable racism embedded within the U.S. “justice” system.

Racism is not specific to the death penalty: North Carolina’s criminal justice system is inherently racist across the board. A major study conducted by the North Carolina Advocates for Justice’s Task Force on Racial and Ethnic Bias reveals that people of color in North Carolina are disproportionately targeted at every level — from the juvenile justice system to the superior court system where death penalty trials are conducted. (tinyurl.com/cop75db) n

No comments:

Post a Comment