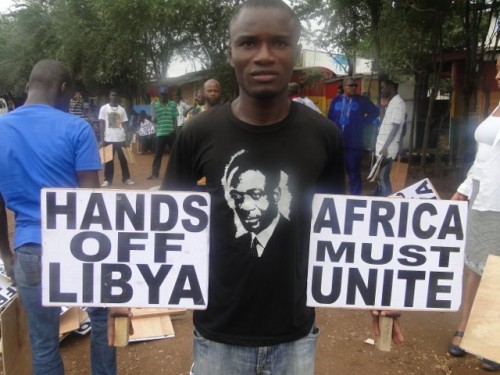

Ghanaians demonstrate against the US-NATO invasion and occupation of the North African state of Libya. These demonstrations coincide with the 102nd anniversary of the birth of Kwame Nkrumah., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

Special Report: Libya’s Foot & Mouth Crisis

By George Grant

Foot & Mouth has ravaged Libyan livestock since the authorities lost control of the disease with the onset of last year’s revolution

Tripoli, 20 November:

When an outbreak of Foot & Mouth disease (FMD) was identified in Zawiya at the end of 2010, the authorities responded accordingly, clearing a ring around the infected area, vaccinating livestock on the perimeter and placing strict controls on animal movements.

When a subsequent outbreak was reported in Zliten at the start of 2011, animal health teams were unable to carry out this procedure after the counter-revolution against the Qaddafi government began.

For the better part of the next year, as war in Libya raged, FMD quietly but rapidly spread. When the rebel authorities finally restarted their work in November 2011 they discovered that FMD, once controlled in Libya, was now everywhere.

“To say the least, the situation was very bad”, says Abdunaser Dayhum, Director of Libya’s National Centre of Animal Health.

“We had outbreaks everywhere, in Benghazi, Tobruk, Derna, Bayda, Marj, Ajdabiya, Sirte, Misrata, Zliten – a lot there –, Khoms, Tripoli, Zawiya, Sebratha, Garyan, Jadu, Sebha, the list goes on.

“We left the disease for one year without doing anything.” The result, Dayhum says, was an FMD crisis of unparalleled proportions in Libya’s recent history.

FMD is an highly infectious and sometimes fatal viral disease that affects cloven-hoofed animals. It can be spread by infected animals through aerosols, through contact with contaminated farming equipment, vehicles, clothing or feed, and by domestic and wild predators. FMD has been known to infect humans, but this is extremely rare.

“The main way to control the disease is to control the movement of animals”, Dayhum, “and we obviously could not do that during the revolution. It was the same for the first few months after the war; we asked the army, but of course they had other responsibilities”.

With only minimal resources, the Ministry of Agriculture began evaluating and attempting to deal with the situation, reliant to a great extent on popular goodwill. “People were working for the country; for the sake of trying to control this disease”, recalls Dayhum. “Vets were volunteering, not taking any money, and many people were paying out of their own pockets”.

The situation was made still more serious by the outbreak of an alternative strain of FMD to the two strains ordinarily encountered in the country, for which insufficient vaccines were available. The so-called SAT2 serotype was confirmed near to Benghazi in February 2012, with the last reported case of that strain back in 2003. The other two strains found in Libya are the so-called A and O serotypes.

Insufficient vaccines were also available to deal with the surge in reported cases of A and O-type FMD. Prior to the revolution, serotypes A and O were still widespread in Libya but the government was largely able to control outbreaks, meaning that a general livestock vaccination programme was not government policy. Consequently, only 500,000 doses of vaccines to treat the A and O variant were held in Libya, for emergency use around an infected area following any reported outbreak.

So far this year, the Ministry of Agriculture estimates that at least 40,000 animals have succumbed to FMD, although the true figure may be much higher. Many livestock may have died on farms and never been reported to the authorities. In Eastern Libya alone, a region in which reported cases of FMD did not exist at all before the US-NATO overthrow of the Gaddafi government, 24 new outbreaks were reported on a single day in February of this year.

Ironically, however, there are likely to also have been many reports of FMD in Libya that were in fact nothing of the kind. “FMD is the ‘Kleenex’ disease in Libya, meaning that whenever anybody finds any seemingly corresponding symptoms, they automatically assume it’s FMD”, Dayhum says.

Other diseases frequently mistaken for FMD in Libya include Bluetongue disease, an often fatal but non-contagious insect-borne virus, and Peste de Petits Ruminants (PPR), otherwise known as goat plague, a contagious disease that affects sheep and goats, and is particularly fatal amongst infants.

Although lab tests have yet to provide confirmation, officials at the Ministry of Agriculture privately believe that the recent potential outbreak of FMD reported in Kufra may in fact be PPR. “They have a serious infection in sheep and goats, but nothing in cattle”, said one official. “Moreover, you would expect with PPR for about 60 per cent of infected infants to die, which is what we have.”

The Ministry is certainly hoping the Kufra outbreak is not FMD, with the town one of the very few in the country that appears to have escaped last year’s spread.

Kufra is fortunate in its remoteness and the relatively sizeable distance between animals, although it is close to the Sudanese border, with FMD also a problem in that country. Little-known is the fact that camels represent a significant danger to owners and traders in a non-affected area such as Kufra, since the beasts are carriers of the disease but are not themselves affected by it.

Economically, the cost of the FMD epidemic in Libya is likely to be vast, although it is impossible to put an accurate figure on it in monetary terms. Losses caused by FMD include reduction in production parameters such as decreases in milk production, weight gain, reproductive inefficiencies and death in young ruminants and swine.

In addition, affected animals cannot work the land or transport agricultural harvests to market. The costs of prevention and control with restrictions in both local and international trade are high, thereby affecting food security and livelihoods along the production and marketing chain.

In fact, the FMD epidemic in Libya coincided with the onset of a major outbreak in Egypt, which the UN’s Food & Agriculture Organisation estimates has put 6.3 million buffalo and cattle and 7.5 million sheep and goats at risk there.

The two may not be a coincidence. “One of the major problems we have is cross-border contamination”, continues Dayhum. “Farmers and traders take their livestock across the borders, often bringing the disease with them.

The nearest case of SAT2 in Egypt is just 100 kilometres from the Libyan border. This means that any approach to tackling the disease has to be regional or it will fail.”

One of the most dangerous times for the introduction of FMD into different parts of the region is Eid. Over the festival, hundreds of thousands of livestock are moved all over the country, with many imported from abroad.

In Tripoli alone this year, imported livestock could be found in markets from countries as varied as Algeria, Chad, Egypt, Morocco, Niger, Sudan and Tunisia. Many of these animals have been brought into Libya “informally”, meaning that the proper checks at the borders have not taken place.

With Libya’s situation already critical, the problem may well have been exacerbated further by the festival.

With animal movement controls near impossible over Eid this year, the Ministry of Agriculture chose to wait until November before enacting a programme it hopes will start to bring the crisis under control.

With the situation so bad, it was decided to scrap the “ring-vaccine” approach and adopt a general vaccination programme. To that end, the government has acquired a total of five million vaccines, including 300,000 doses for the treatment of SAT2.

The government estimates that the total number of vaccines broadly corresponds to the number of livestock currently in Libya. Prior to the revolution, it is estimated that there were around seven million livestock in Libya meaning that the conflict may have cost the country as many as two million animals.

There are now 200 three-man teams (each with one vet and two assistants), spread out across Libya aiming to complete the vaccination programme in just 50 days. Every animal is being injected with a bivariate vaccine for the A and O serotypes, whilst all cattle, of which there are an estimated 100,000 in Libya, are being injected with the SAT2 vaccine.

How successful the programme will be remains to be seen, but one positive upshot will be that the government will acquire accurate data on the total number of animals and farms in Libya for the first time. A small comfort under the circumstances, but something that may at least assist the government in preparing its strategy for dealing with future outbreaks, if and when the present crisis is brought under control.

No comments:

Post a Comment