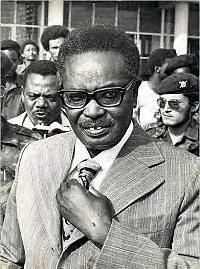

President Agostino Neto as leader of the MPLA and the People's Republic of Angola, first invited the Cuban Internationalists to Angola in 1975., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

Action that began the Angola People’s Struggle

14 Thursday Feb 2013

Alicia Céspedes Carrillo

FEBRUARY 4, 1961 marked the beginning of the armed struggle of the Angolan people against Portuguese colonialism.

After World War II, with the aftermath of destruction and social uncertainty in Europe and around the world, progressive decolonization was a fact and this reality was embodied in the Charter of the United Nations. Portugal, which was economically dependent on its role as a commercial intermediary, partially based its economy on the wealth obtained from natural, social and economic resources of its colonies.

Decolonization, as a result, would harm its interests. In order to avoid submitting to a decolonization process, Portugal used legislative reform in relation to colonies and slavery, re-designating their offshore colonies as overseas provinces, with cultural differences.

As a result, the UN Secretary General charged the Fourth Commission of the General Assembly with looking into and confirming whether, according to pertinent established parameters on the subject, Portuguese territories enjoyed self-determination or not. Four years later, the Fourth Commission presented the United Nations XV General Assembly with a list of 12 principles, including the grounds upon which they categorized Portuguese possessions as non-self-determining. The commission’s report concluded that “there was a prima facie obligation to transmit information … on territories geographically separate and ethnically and/or culturally distinct from the administering country.” With these guidelines establishing the legal framework for categorizing non-self-determining territories, the General Assembly decided to categorize Portuguese territories as “non-self-determining”, in line with Chapter XI of the Charter and its legal requirements. In other words, they were colonies.

Nevertheless, the Portuguese government ignored the U.N. recommendations and resolutions, attempting to withhold from the African people their right to long-awaited freedom, after being subjugated and enslaved for almost 500 years. Far away, the Fascist Portuguese government, using their repressive forces, including the PIDE (International State Defense Police), Secret Police and other bodies, who in a single wave of indiscriminate detentions against members of the clandestine revolutionary movement of Luanda, primarily, charged many rebels in what became known as the “Trial of the Fifty”.

Oddly, on the PIDE list of detainees appears the name of Francisco Javier Hernández described as a Cuban seaman.

According to reports from members of the Angolan clandestine movement, this Cuban was a crew member on a ship that traveled between the colonies, Brazil and Portugal who, along with Angolan crew members, joined in the effort, acting as a courier and support in delivering documents and information to revolutionaries in the colonies.

Presumably he was a member or affiliate of the seamen’s union to which his colleagues belonged. After being taken out of prison, nothing was ever heard of Francisco Javier again, and given the way he was removed, it is assumed that he was one of those later murdered by repressive fascist organizations. Subsequent efforts to determine details of his disappearance have been unsuccessful.

The randomness of the arrests and the suffering imposed on detainees created the mood in the prisons and around the country.

Demands for independence were silenced by the use of prison, deportation, torture and repressive measures. The United Nations Declaration of December 1960 (Resolution 1514) declared that “The subjection of peoples to alien subjugation, domination and exploitation constitutes a denial of fundamental human rights, is contrary to the Charter of the United Nations and is an impediment to the promotion of world peace and co-operation.” Among the revolutionary forces arose the progressive conviction that the Portuguese metropolis was not willing to concede a change regarding its overseas territories.

Meanwhile, in the case of Angola, the Angolan Liberation Movement (MPLA) established in 1956, with an extensive political and diplomatic background, declared that given Portuguese intransigence, the only recourse was to proceed to armed struggle – the only route to independence.

Thus on April 4, 1961, rejecting the Portuguese designation of Angola as an overseas province, and demonstrating the fallacy of this designation, the clandestine MPLA movement in Luanda, with three rebel commands, staged an armed assault on various Portuguese military installations in the city, principally the São Paulo civil prison, the city police precinct and the rural police post, with the daring objective of freeing political prisoners and drawing attention to the struggle’s just cause.

Near the Estación Nueva train station in the Rangel shanty town area they set up a rebel command post, which was later moved to the Pedreros district in the capital itself. The house functioned as the base of General Commander, Paiva Domingos da Silva, who was accompanied by two of the oldest curandeiros and a girl aged seven or eight, the “queen”, named Engracia, who was given the task of watching over the “iron cauldron”.

Preparations for action involved not only strategic and military planning but also a religious invocation in which all the combatants participated. The order was given on February 2 for the uprising on February 4.

On the night of the 3rd the conspirators gathered at the home of combatant Imperial Santana, second in command of the operation; ten groups that were to attack the Portuguese installations departed at 3.30am on February 4.

The revolutionaries took advantage of the fact that there were many foreign journalists in the capital covering the expected arrival in Luanda of the ship Santa María which had been steered off course by its retired Portuguese captain, Henrique Galvão, a former deputy in Salazar’s 1947 government.

Henrique Galvão had spoken out against Salazar’s dictatorship in a public letter in which he had denounced the situation in Angola. He was arrested as a result but managed to escape from prison in 1960.

The MPLA followed the progress of the Santa María with great interest, although they claimed to have no direct relationship with it. They considered the action not an act of piracy, as Salazar’s government was claiming to the rest of the world, but rather a prelude to other acts which would be carried out later.

On January 27, before being allowed to disembark, the MPLA required Galvão to define his position with regard to the liberation movement and to separate his insurrection plan from that of the MPLA.

The outcome of the MPLA’s planned attack on the oppressor’s installations and other related offensives was expressed in the communiqué that the MPLA’s Directive Committee published entitled Massacres in Luanda.

“…In the early hours of February 4, groups of Angolan nationalists mounted an armed attack on military and civil prisons in Luanda. There was heavy fighting with the oppressive colonial forces in their endeavor to take over detention centers housing hundreds of political prisoners.

“The communiqué issued by the Angolan General Government informs of seven fatalities on the side of the colonial troops and nine nationalists, as well as a number of casualties and numerous captives. On February 5, during the funeral organized by the fascist administration for its seven soldiers, there were further confrontations between Angolan patriots and the colonial army, with a resulting four fatalities.

“Naturally, the official figures of our fallen in this battle against the political apparatus installed in Luanda by Salazar’s dictatorship does not bear any relation to true facts.

“The Directorate of the MPLA calls for the attention of the international community … for a considerable time the people of Luanda, incensed by the repressive methods of the Portuguese Gestapo (the PIDE, International State Defense Police)… that does not exclude any mass extermination method – from poisoning food given to prisoners to summary execution of 25 of them in November 1960… This is proof of how the Portuguese government … insists on maintaining its class-based domination and system of oppression… These events are proof of how the action against Salazar’s dictatorship marked the beginning of Angola’s first War of Independence”.

“The armed insurrection in fact proved the lie in the Portuguese government’s version that the incidents were “undertaken by a small group of foreign terrorists who had infiltrated the Portuguese overseas province to create disorder … and attempting to create an international environment which would give rise to the break-up of Portugal…” Cynical words from the Portuguese government trying to justify itself in the face of the horrifying situation of the Angolan people and to hide behind the hackneyed term, “foreign terrorists”.

This action, like the assault on the Moncada Garrison, was not successful, but, like Moncada, it ignited the flame of revolution which ended with the triumph of the Angolan people.

After decades of military, political and diplomatic struggle, the sacrifice of the Angolan people was not in vain, they can be proud of having defended their independence and sovereignty and they can continue to build, with social justice, an ever more flourishing country.

No comments:

Post a Comment