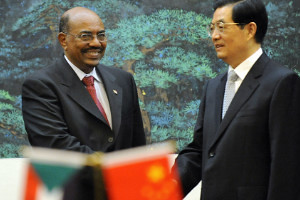

President of the Republic of Sudan and the former leader of the People's Republic of China. The two states have developed close cooperation over the years., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

China's Sudan challenge

By Giorgio Cafiero

Sudan and China have enjoyed cordial relations for decades, developing a fruitful economic and political partnership dating back to their mutual estrangement from the West in the late 1980s and early 1990s. But Sudan's 2011 partition has presented China with a new set of challenges.

The ongoing failure of Sudan and South Sudan to resolve tense standoffs over oil ownership, border demarcation, and the status of the disputed Abyei region constitutes a delicate dilemma for China.

Namely, Beijing will be challenged to advance its interests in the Sudans while upholding its foreign policy principle of non-intervention in other states' affairs.

Since the 2011 partition of the country, China's dual objective has been to maintain its alliance with Sudan while establishing a cooperative partnership with South Sudan, which controls 75% of all Sudanese oil. The crisis along the Sudanese border is forcing

China to at least consider adopting a policy of shuttle diplomacy that it has not previously embraced, threatening China's historically non-interventionist bent.

Historical context

In 1989, as the Tiananmen Square crackdown in China and the Bashir-Turabi coup in Sudan increasingly alienated both Beijing and Khartoum from Western powers, Sudan began to look east. This dynamic paved the way for a strong China-Sudan partnership. Beijing provided the National Islamic Front-run regime, led by current president Omar al-Bashir, with low-interest loans and weapons transfers, while Sudan opened its vast oil reserves to China. By 1996, the state-owned China National Petroleum Company (CNPC), along with Malaysian and Indian oil companies, had taken control of most of Sudan's oil. In the past two decades, China has invested over $10 billion in Sudan.

Today, China is Sudan's top trading partner, purchasing 70% of Sudanese oil exports in 2010. When Sudanese oil exports reached their peak, 6% of China's total crude oil consumption came from Sudan.

In addition to maintaining the flow of money to Khartoum while Western companies have withdrawn from the country, China's veto power has provided the Sudanese regime with impunity at the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). Beijing's threat to veto all resolutions targeting Sudan has empowered Bashir's regime to pursue its aggressive policies in Darfur without the threat of economic sanctions being imposed by the UNSC.

The financial, diplomatic, and military support that Beijing has lent the Sudanese regime during its conflicts with periphery factions predictably infuriated the South Sudanese.

Nonetheless, following the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) that concluded Sudan's second civil war, China accepted southern independence as an inevitable outcome.

China's leaders understood that securing a partnership with the southerners would be essential for ensuring access to the majority of Sudanese oil. Indeed, when 98.5% of South Sudan's voters favored independence during the January 2011 referendum, and South Sudan gained official independence in July, Beijing immediately engaged the southerners diplomatically. China was one of the first states to establish a general consulate in Juba, and South Sudanese politicians - including current South Sudanese president Salva Kiir Mayardit - were invited to China, where they were promised robust Chinese investment.

But it became clear almost immediately following South Sudan's independence that the sensitive issues relating to oil ownership, border demarcation, and the status of Abyei - all left unresolved under the CPA - would prove highly problematic for the North-South bilateral relationship.

The majority of Sudanese oil fell under Juba's control, yet the means to refine and export it remained under Khartoum's, meaning cooperation would be necessary.

However, the two sides have failed to reach an agreement on these sensitive matters. In January 2012, South Sudan shut down its oil production after it accused Sudan of stealing its oil exports en route to Port Sudan on the Red Sea.

In April, hostilities reached their peak when the Sudans engaged in a military confrontation over disputed oil reserves along the border of Southern Kordofan state in the North and Unity state in the South.

Together, these reserves account for about 60% of all known Sudanese oil deposits. On April 10, South Sudan launched an offensive to seize control of the oil hub in Heglig, Sudan - a target of vast geostrategic importance, given the 60,000 barrels a day of oil that it exports. South Sudan maintained its control over this border town for 10 days until Sudan's warplanes bombed the area and dislodged South Sudanese troops and their Sudanese proxies.

As these tensions came to a head, South Sudanese President Kiir was on a diplomatic trip to China. Kiir reportedly complained to Chinese officials that their close ally in Khartoum had "declared war" against South Sudan by bombing Heglig several days earlier. Finding its own oil interests caught in the crosshairs of a tense North-South standoff, China echoed the United States, urging both sides to resolve their territorial disputes through dialogue and to avoid military force. Kiir left China some three days before he was scheduled to depart, suggesting that he had found China's response inadequate.

While Sudanese leaders have met with their southern counterparts on numerous occasions following the episode last April, both sides have failed to implement the terms of a peace agreement signed in September meant to resolve the conflict. In January of this year, Sudanese and South Sudanese officials met in the Ethiopian capital to negotiate a 14-mile demilitarized zone. Yet the scope of this zone and Sudan's accusations that Juba sponsors armed rebels in Sudan's South Kordofan and Blue Nile states - a charge denied by South Sudanese officials, who claimed that these rebels were a domestic issue for Sudan - undermined the prospects for conflict resolution.

War and peace cost-benefit analysis

Most analysts concur that although neither side wants war, both capitals seem to believe that by delaying the signing of a diplomatic resolution, they have room to advance their long-term interests. The weakened positions of both Sudans drive their mutual interest in avoiding any full-scale war. Sudan is militarily superior, yet Khartoum's capacity to score a military victory is jeopardized by pro-Juba proxies in its southern regions.

Moreover, as the partition of Sudan has dramatically decreased the oil supply under Khartoum's control, the state has much less revenue and a war would only worsen the country's dire economic conditions.

Similarly, South Sudan is one of the world's least developed countries. Over half of its citizens live below the poverty line. Its infant mortality and maternal mortality rates rank near the top of the world, while its 27-percent literacy rate ranks near the bottom. War would only exacerbate these conditions, and with oil sales constituting 98% of Juba's budget, southern leaders know that they must begin exporting oil to meet their people's needs. This cannot be accomplished with Sudan bombing their oil fields.

Still, both sides rightly consider the demarcation of oil fields to be a vital national interest. Some analysts also contend that Juba is benefiting from the tense standoff, with the threat from Khartoum uniting a South Sudan still grappling with the challenges of state-building and simmering ethnic conflicts.

But as the political risks associated with greater investment in the oil-rich region grow higher, the one party that has nothing to gain from the status quo is China. The question is what cards China has to play.

South Sudan's leaders understand that Chinese firms are well placed to serve the country's dire need for hospitals, telecommunications, schools, and infrastructure, Thus, China is well positioned to attach strings to development projects to push South Sudan toward concessions. As Khartoum depends on China for oil exports, loans, infrastructure projects, arms for the Darfur conflict, and its veto powers in the UN Security Council, Beijing is in a strong position to pressure the Bashir regime toward concessions.

However, the Chinese may calculate that diplomatic efforts are likely to prove futile as certain factors driving the Sudans' standoff remain outside Beijing's sphere of influence. The recent kidnapping of several Chinese workers in Darfur and the rise of militant Islamic extremism throughout the region highlight additional political risks.

If Beijing concludes that the costs of doing business in the region outweigh the potential benefits, China may back off and focus on longer-term interests in the Sudans. If this scenario unfolds, China may turn its attention to other states, such as Iraq and Venezuela, for oil until the Sudans resolve their standoff on their own.

Regardless, the tense crisis between the Sudans is compelling China to at least question how well "non-interference" advances Beijing's geostrategic interests. If Beijing does successfully engage in shuttle diplomacy between Khartoum and Juba, it may be indicative of a new China that views its responsibilities as a rising super power differently.

Giorgio Cafiero is a independent foreign policy analyst and contributor to Foreign Policy In Focus.

No comments:

Post a Comment