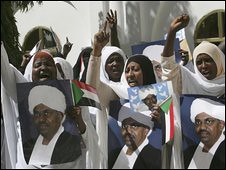

Sudanese masses demonstrate against imperialist plot to overthrow the state. The ICC has issued a warrant for the arrest of President Omar al-Bashir., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

Why is the International Criminal Court picking only on Africa?

By David Bosco

Friday, March 29, 1:03 PM

David Bosco is an assistant professor at American University’s School of International Service. His book on the International Criminal Court, “Rough Justice,” will be published this fall. Follow him on Twitter: @multilateralist .

Almost 15 years ago, delegates from more than 100 countries gathered in a crowded conference room in Rome, cheering, chanting and even shedding a few tears.

After weeks of tense negotiations, they had drafted a charter for a permanent court tasked with prosecuting genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes around the world.

Kofi Annan, then U.N. secretary general, cast the new International Criminal Court in epochal terms: “Until now, when powerful men committed crimes against humanity, they knew that so long as they remained powerful, no earthly court could judge them.”

That earthly court is now rooted. Its glassy headquarters on the outskirts of the Hague houses more than 1,000 lawyers, investigators and staff members from dozens of countries. Judges hail from all regions of the world.

But for an institution with a global mission and an international staff, its focus has been very specific: After more than a decade, all eight investigations the court has opened have been in Africa. All the individuals indicted by the court — more than two dozen — have been African. Annan’s proclamation notwithstanding, some very powerful people in other parts of the world have avoided investigation.

The court began its work in Uganda and Congo, where it focused mostly on crimes by militia groups (one key militia leader accused of crimes in Congo surrendered to the court this month). In 2005 came a major investigation into allegations of genocide and ethnic cleansing in the Darfur region of Sudan. Then the court launched inquiries in the Central African Republic and Kenya. And in 2011, the prosecutor opened an investigation of violence in Ivory Coast.Around the same time, the ICC jumped into the Libya imbroglio, ultimately indicting Moammar Gaddafi, his son and the regime’s intelligence chief. Most recently, the court announced its intention to scrutinize atrocities in Mali.

African leaders have taken note of the ICC’s intense interest in their continent. The backlash swelled after the court indicted Sudanese President Omar Hassan al-Bashir in 2009. Many African officials argued that the court’s intervention would torpedo chances for a negotiated solution to that country’s conflicts. Several African governments pushed the court to reconsider.

The African Union, which represents more than 50 nations, even instructed its members that they had no legal obligation to arrest Bashir. Malawi’s president complained that “subject[ing] a sovereign head of state to a warrant of arrest is undermining African solidarity and African peace and security.”

To this day, the A.U. has refused to allow the ICC to establish a liaison office at its headquarters. There are even plans for an African criminal court that might displace the ICC.

Former A.U. chairman Jean Ping has suggested to journalists that the court is a neocolonial plaything and that “Africa has been a place to experiment with their ideas.”

At an African summit meeting in 2009, he accused the ICC of ignoring crimes in other parts of the world: “Why Africa only? Why were these laws not applied on Israel, Sri Lanka and Chechnya and its application is confined to Africa?”

1 comment:

George Bush, Dick Cheney this list could get long

Post a Comment