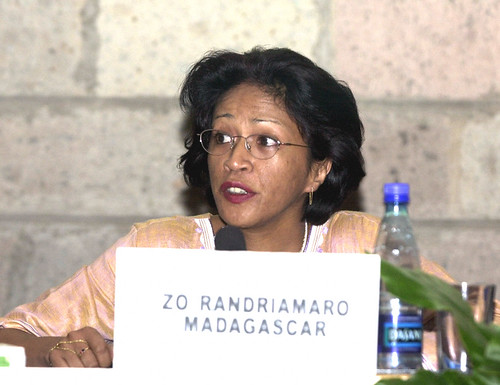

Zo Randriamaro is a human rights and feminist activist from Madagascar, currently acting Executive Director of Fahamu Africa. She presented at the United Nations African Institute for Economic Development and Planning Monthly Seminar on March 5, 2013., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

Women and political economy of care

Tuesday, 12 March 2013

The concept of social reproduction — that is the process that makes it possible for individuals, families, and society itself to continue — provides the framework for this article, which is premised on the existence of a silent and hidden crisis that is affecting the invisible and undervalued realm of the real economy, for instance the care economy which is a crucial dimension of the process of social reproduction and relies on the unpaid care work performed mainly by women for sustaining families, households and societies on a daily and generational basis.

While care work is located in many different areas of the economy — ranging from the family to paid employment, and is performed on behalf of a wide range of care recipients, this article focuses on “unpaid care work” that is not considered work within the System of National Accounts (SNA), and includes but is not limited to housework (collection of fuel and water, meal preparation and cleaning, among other tasks) and care of persons (children and/or the elderly, the sick and the disabled) carried out in homes and communities. Such work is a key component of social investment and is critical to well-being.

It also fuels economic growth through the formation of human capital and reproduction of a labour force that is healthy, productive and possesses the basic human capabilities.

The monetary value of such work would constitute between 10 and 39 percent of a country’s gross domestic product.

In this article, “social reproduction” is defined as a multi-faceted concept that can pertain to a variety of subjects, including the labour force, the social fabric or capital. As underlined by Diane Elson, “social reproduction is contested, contradictory and may be unsustainable.” For instance, the recent history shows that the global food, financial and economic crises have threatened the social reproduction of human beings, as well as the social reproduction of capitalist money in the banking system, together with the social reproduction of capitalist production.

Of note is the social reproduction of primitive capitalist accumulation, which also highlights the interconnections between the various aspects of the concept.

Thus, the social reproduction (renewal) of primitive capitalist accumulation has taken the contemporary forms of land grabbing, and use of migrant labour by some transnational corporations to address the difficulties — resulting from the crisis of the social reproduction of the labour force — in the availability of local labour force in the extractive sectors of mineral-rich countries like South Africa. In contrast to this type of social reproduction, very little thought and investment has been given by policy-makers to addressing the crisis of the care economy, which mainly affects women.

This is the reason why the crisis of social reproduction on which I want to focus is the one that has affected African women for decades, and mirrors structural inequalities at both global and local levels. It is about “the systemic crisis of livelihoods and reproduction of the labour force” (Bernstein, 2003: 220) that started with the famines in the 1970s, and was compounded by the HIV and Aids pandemic later on.

This crisis was described as follows by Kofi Annan (2003): “a combination of famine and Aids is threatening the backbone of Africa — the women who keep African societies going and whose work makes up the economic foundation of rural communities.”

It appears that one of the root causes of the neglect of this enduring crisis by the powers-that-be is that the primary subjects of the reproduction process are women, who are not paid for their work, although this work is directly productive of value.

As Dalla Costa (1995) and others put it, “since housework has largely been unwaged and the value of workers’ activities is measured by their wage, then, women, of necessity, have been seen as marginal to the process of social production.”

Why a political economy approach

There is need to address the limitations of the current human rights paradigm and practice in recognizing and responding to the dual crises of social reproduction and care. In particular, a political economy approach allows us to understand the link between these crises and relations of power and domination at local and global levels, thereby avoiding to disconnect the problem from its underlying causes and consequences, and to obscure the share of responsibilities and obligations between states and other actors.

In contrast to conventional economics, a political economy approach highlights the interlinkages between the economic, social and political realms, and how power operates through the structured relations of production and reproduction that govern the distribution and use of resources and entitlements within households, communities and society.

A political economic approach allows one to de-bunk the myth of the unitary household model, and to make visible the hitherto hidden linkages at different levels with power relations that underpin the global economic order and macroeconomic policies, as well as the intersections with issues of class, race and other variables. The political economy analysis points to three key elements that affect both the depth and prevalence of the crises of care and social reproduction.

First is the sexual division of labour within the public and private spheres, which is underpinned by gender norms and ideologies that hold women primarily responsible for unpaid work in the households, thus creating inequalities in bargaining power in the household between men and women. Caring professions in the public sphere and labour market that are similar to the “feminine” unpaid care work are also undervalued, while the detachment of unpaid care work within the human rights movement from the broader struggle for social and economic equality has led to its perception as women’s only problem.

The second element is the contemporary global macroeconomic environment. Neo-liberal free market policies and the quest for cheap sources of labour and maximum profit have disrupted local economies and dramatically changed labour markets through deregulation, flexibilisation and casualisation of work.

It is in this context that on the one hand, women from developing societies have entered into wage employment on an unprecedented scale. On the other hand, the neo-liberal policy environment has also led to their increased workload in the market and at home, and to the feminisation of poverty, especially among unskilled and marginalised poor women, who lack access to productive resources and basic capabilities (Erturk, 2009).

Such poverty, marginalisation and lack of protective mechanisms, make women easy targets for abuse and undermines the prospects for the progressive realization of their rights (Elson, 2002).

The third key element highlighted by the political economy analysis of care is related to the gendered impacts of globalisation, which have involved in many instances the ‘privatisation of public services and infrastructure that regresses women’s rights by placing greater burden on their labour in the household, as well as the establishment of political and legal systems with limited or no significant participation by women’ (Erturk, 2009: 12).

Current trends and prospects in the care economy

The time use surveys that have been conducted in Africa during the last decade have provided a strong basis for quantifying unpaid care work, and for providing estimates of its overall magnitude and its distribution between men and women. In spite of the recent progress in terms of data collection, the paucity of information about the care economy in Africa and in other regions reflects the policy gap in relation to unpaid care work as well as the absence of a coherent theory of the relationship between the family, the market, and the state (Folbre, 2012).

This is partly due to the fact that most economists and scholars have overlooked the two-way connection between the local and the global, as expressed in the proposition resulting from the work of Smith and Wallerstein on households, which is based on the assumption that global economic processes shape the structure and economic functions of households at a given time. They have specifically underlined the increased importance of households to processes of social reproduction in times of global economic crisis.

In line with the prevailing trend in developing countries (UNRISD, 2010), the results of surveys conducted in a range of African countries, from Guinea (Bardasi and Wodon, 2010 cited by Folbre, 2012), South Africa, Benin, Madagascar, to Mauritius and Ghana (Charmes, 2006 cited by Folbre, 2012) show that adult women and girls work longer hours overall than adult men and boys.

Women’s central contribution to agricultural production, especially for subsistence consumption, accounts for a large part of this pattern in Burkina Faso, Kenya, Nigeria, and Zambia, where women spend substantially more minutes per day than men in agricultural production (Kes and Swaminathan, 2006:18 cited by Folbre, 2012). In their detailed analysis of South African surveys, Floro and Kimatsu (2011, cited by Folbre, 2012) find that women’s domestic responsibilities seemed to hamper their ability to earn income.

The marketisation of care

Since 2003, researchers have called for attention to a growing crisis of social reproduction that is most severe among the poorest segments of the populations in developing countries, due to the fiscal crisis of the state and the policy choice for cutbacks in public provisions for social services (Gill and Bakker 2003).

These authors have pointed to the dual processes of “wider privatisation” of state functions and “reprivatisation” of key institutions of social reproduction (education, health and social services) as part of the on-going neo-liberal reforms (Gill and Baker 2003).

Those reforms also involve a new framework for resource allocation for social and individual welfare between the state, the family, the market and the voluntary and informal sectors. In this new framework, social life is marketised with the commodification of spheres of society that were previously shielded, and citizens having become responsible for helping themselves.

This marketisation of citizenship has resulted in crises and transformations in social reproduction, and has led to worsened human insecurity, with increased struggles for survival among the poorest.

In addition to the neo-liberal policies aimed at the free movement of capital and deregulation, all these circumstances have required a return to community-based survival strategies (reprivatisation) that rely primarily on women’s initiatives and labour (Hunter, 2005).

— Pambazuka News.

Zo Randriamaro is a human rights and feminist activist from Madagascar, currently acting Executive Director of Fahamu Africa. This article was presented for the first United Nations African Institute for Economic Development and Planning (IDEP) Monthly Seminar on 5 March 2013.

No comments:

Post a Comment