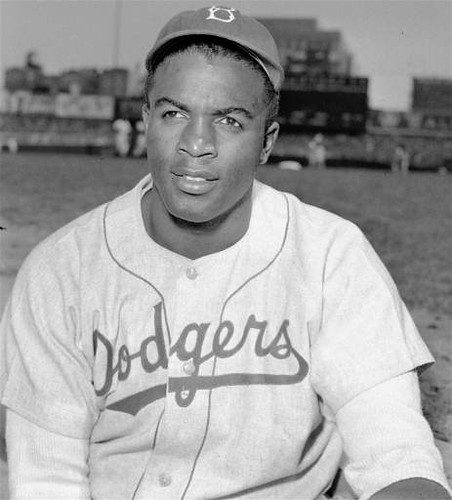

Jackie Robinson was the first African-American to enter Major League Baseball 62 years ago on April 15, 1947 with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Over the last few years the black presence in Baseball has declined tremendously., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

Have African-Americans Left Baseball?

by Keli Goff

Friday, April 19, 2013 11:45 AM

From New America Media and The Root:

While the Jackie Robinson biopic 42 has become a certified success, attracting a diverse audience on its way to becoming No. 1 at the box office during its opening weekend, black Americans are still facing barriers to the baseball field.

The opening of 42 occurred several days before the annual celebration of Jackie Robinson Day -- April 15, the day Robinson officially broke the color barrier -- when every baseball player, manager, coach and umpire in Major League Baseball sports his number, 42. But in recent decades, the number of African-American players has decreased with each passing year.

According to reports, the representation of African-American players in professional baseball is at its lowest point since Robinson and others first began integrating the game, at just around 8 percent. That marks a significant decline from the 1970s, when some estimates placed the representation of black players at around 27 percent. Baseball historian Rob Ruck says the percentage of African-American players was probably closer to 19 percent in the 1970s, while the 27 percent number likely includes Afro-Caribbean and Afro-Latino players.

The decline of African-American participation in baseball is a stark contrast to the days of the Negro Leagues, which nurtured Robinson, when baseball was seen as more than a mere sport but was also a community pastime. The reason for the sport's decline in black American communities is complex and multilayered.

Cost Is a Factor

Baseball Hall of Famer Dave Winfield, who is African American, currently serves as executive vice president and senior adviser of the San Diego Padres. He chalked up the decline in African-American participation in the sport to "the three C's," which, he told The Root, stand for continuity, cost and competition. Continuity, he explained, means the importance of consistent exposure to the sport throughout a player's school years, something that is less likely to happen today because of the second C, which is cost.

Baseball "didn't cost me much as I grew up," he said. "There were no travel teams/club teams, tournaments you have to pay for now." He then explained the third C, competition. "When I grew up, baseball was No. 1 in America. Now it has the competition of the other sports -- NBA, NFL, golf, you name it."

Ruck, author of Raceball: How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and Latin Game, echoed Winfield's sentiments regarding the financial barriers to the sport that now exist for many poor kids, a socioeconomic reality disproportionately represented in communities of color. Little League and club expenses as well as travel can run between $3,000 and $5,000 annually, expenses that by default make economic and racial diversity less likely among participants.

Charles Clark is the only African-American manager of a Little League team in North Tampa, Fla. In an interview with The Root, he discussed his firsthand experience with the costs. "A typical quality baseball bat for a child is $300." Clark has three sons, all of whom participate in the sport, meaning he spends a minimum of close to $1,000 on bats alone, which pales in comparison to the other potential costs.

Clark explained that while there is Little League, in which nonprofit teams are sponsored by local businesses, and all kids have an opportunity to play, travel ball has become big business. Travel ball teams are where Little League's best and brightest compete. The fees to participate in such a team can cost between $500 and $1,200, not including uniforms and other miscellaneous expenses.

Though Little League exists as a lower-cost option for those who can't afford the expense of travel ball, Clark explained that for kids hoping to go pro, "they would need the exposure of being in travel ball." That's where scouts, coaches and professional baseball players and others connected to the MLB discover future stars. The class divide in baseball, however, extends far beyond childhood.

According to Ruck, "Very few black kids go to college to play baseball. Last decade it was, like, under 5 percent of all NCAA baseball players on scholarship were black, versus 10 to 15 times higher in basketball and football. The reason is twofold. If you play college football or basketball, you get a full scholarship. If you play college baseball, you might be one of 25 to 35 kids who are splitting 11.7 scholarships, so you don't get a full scholarship. You might get a quarter scholarship or half scholarship. If you can't afford the rest of that, you're not going to play baseball but a sport that can give you a full ride."

Fathers Play a Significant Role

Clark's involvement in the sport at the Little League level highlights another reason cited by Ruck for the decline in baseball in the African-American community: fathers. Ruck explained that baseball is a sport defined in part by the bond between fathers and sons. Boys learn to play catch at an early age, usually with a father. (This is such a defining cultural image that it is currently being parodied in a popular car commercial.)

Ruck explained, "When we start to see the collapse of the two-headed household -- which I think hits black families because of class reasons more than white families -- you no longer have boys who grow up in homes with fathers who teach them the love and the lore of the game." Clark agreed that baseball is a sport in which the role of fathers is particularly important.

"Cultural cachet" is also cited as a reason for the sport's decline in popularity, with certain sports carrying a level of prestige on various continents and within communities. For instance, soccer is a much more popular sport in Brazil, making it more likely that a young Brazilian will grow up wanting to be a professional soccer player, just as a young Canadian is more likely to grow up wanting to be a professional hockey player.

"Everybody wants to be like Mike," Ruck said, referring to Michael Jordan, the African-American basketball icon who influenced an entire generation of aspiring black athletes.

Integration Crippled Negro Leagues

But perhaps the biggest reason baseball has declined in the African-American community is the most ironic reason of all: Jackie Robinson. Once the MLB was integrated, the Negro Leagues collapsed. While white executives who opposed integration worried that black players would scare white fans away, instead white fans stayed, and black fans came in droves.

"Jackie Robinson allowed the Brooklyn Dodgers to set attendance records," said Ruck. "The Pittsburgh Courier, the black newspaper, said, 'Jackie's nimble. Jackie's quick. Jackie makes the turnstiles click,' " a testament to Robinson's popularity with fans.

"Major League Baseball ends up profiting immensely in terms of fans, in terms of great players," Ruck continued. "But they don't bring in black teams -- they could have brought in the Newark Eagles or the Homestead Grays or the Kansas City Monarchs [Negro League teams]. They don't bring in black ownership. They don't bring in black managers or front-office people, and for the next 40 years, the front office and managerial ranks and ownership ranks are almost exclusively white."

Ruck went on to explain that by not incorporating Negro League teams into the minor-league operations, where the MLB continued to groom, nurture and recruit its future stars for years, major-league integration essentially gutted the Negro Leagues, leaving them with no audience. Worse, it left black players who were not superstars like Robinson with no infrastructure like the sandlot community clubs, which operated as the minor-league equivalent to the Negro Leagues; those clubs disappeared, too.

That left aspiring black ballplayers with few options for training and being discovered, particularly since, as demonstrated in the film 42, the minor leagues were concentrated in the South. This made pursuing a career there not a particularly attractive proposition for African-American men, especially those who did not have a high-profile sponsor and protector like Robinson did in Dodger General Manager Branch Rickey.

Ruck did say, though, that ultimately there might be more important issues to focus on than the lack of diversity on baseball diamonds. "I don't think this is a big problem for black America not to have as many baseball players as it once had. I think African Americans in this country are well-represented in athletics. I think I'd like to see more ownership, more front office. I'd like to see positions of power off the field increase the ranks of African Americans. But I think if anything, one could argue that there's too much of a focus on sports in black America, to the detriment of education and vocation."

Author Bio:

Keli Goff is The Root's political correspondent.

No comments:

Post a Comment