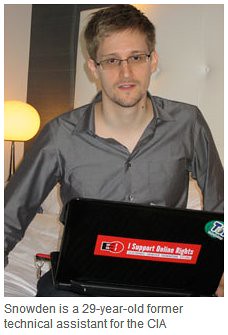

Edward Snowden is being sought by the United States government after he was fingered for exposing the massive surveillance against the peoples of the world by the National Security Agency (NSA)., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

June 10, 2013

U.S. Preparing Charges Against Leaker of Data

By MICHAEL S. SCHMIDT, ERIC SCHMITT and KEITH BRADSHER

New York Times

WASHINGTON — As Justice Department officials began the process Monday to charge Edward J. Snowden, a 29-year-old former C.I.A. computer technician, with disclosing classified information, he checked out of a hotel in Hong Kong where he had been holed up for several weeks, according to two American officials. It was not clear where he went.

Whether Mr. Snowden remained in Hong Kong or fled to another country — like Iceland, where he has said he may seek asylum — the charges would strengthen the Justice Department’s hand if it tries to extradite him to the United States. One government typically must charge a suspect before another government will turn him over.

“There’s no hesitation” about charging Mr. Snowden, one of the American officials said, explaining that law enforcement officials had not been deterred by the debate inside and outside the administration about its leak investigations. The brazenness of the disclosures about some of the National Security Agency’s surveillance programs and Mr. Snowden’s admission in the newspaper The Guardian on Sunday left little doubt among law enforcement officials, the official said.

Officials at the White House, the Justice Department and intelligence agencies declined to comment on Monday on the investigation and on Mr. Snowden.

Senator Dianne Feinstein, a California Democrat who is the chairwoman of the Intelligence Committee and has praised the programs’ effectiveness, said the panel would hold a closed briefing for all senators on Thursday to hear from N.S.A., F.B.I. and Justice Department officials. A similar closed hearing is scheduled for Tuesday in the House.

In Hong Kong, legal experts said the government was likely to turn over Mr. Snowden if it found him and the United States asked, although he could delay extradition, potentially for months, with court challenges, but probably could not block the process. The Hong Kong authorities have worked closely with United States law enforcement agencies for years and have usually accepted extradition requests under longstanding agreements, according to Regina Ip, a former secretary of security who serves in the territory’s legislature.

“He won’t find Hong Kong a safe harbor,” Ms. Ip said.

The Mira Hotel said Mr. Snowden had stayed at the hotel but checked out on Monday.

The Justice Department investigation of Mr. Snowden will be overseen by the F.B.I.’s Washington field office, which has considerable experience prosecuting such cases, according to one of the officials. The department’s investigation into Mr. Snowden is one of at least two continuing government inquiries. The N.S.A. began trying to identify and locate the leaker when The Guardian published its first revelations on Wednesday, and there were indications that agency officials considered Mr. Snowden a suspect from the start.

According to Kerri Jo Heim, a real estate agent who handled a recent sale of a Hawaii home that Mr. Snowden had been renting, the police came by the house Wednesday morning, perhaps even before The Guardian published its story. The police asked Ms. Heim if they knew Mr. Snowden’s whereabouts. Mr. Snowden moved last spring to the house on Oahu, 15 miles northwest of Honolulu, in a neighborhood populated by military families tied to the nearby Schofield Barracks, an Army base.

The N.S.A. investigation is also examining the damage that the revelations may have on the effectiveness of programs. James R. Clapper Jr., the director of national intelligence, said over the weekend on NBC News that he was concerned about “the huge, grave damage it does to our intelligence capabilities.” He did not cite specific examples of the damage caused by the disclosures.

Members of Congress criticized Mr. Snowden on Monday. He “has damaged national security, our ability to track down terrorists, or those with nefarious intent, and his disclosure has not made America safer," said Representative Jim Langevin, a Rhode Island Democrat on the House Intelligence Committee.

The string of articles describing the surveillance programs will probably prompt a broad review within government agencies on granting federal workers and private contractors access to classified data.

Three years ago, the State Department significantly tightened access to its classified data, in reaction to the release of department cables to WikiLeaks by a low-level intelligence analyst, Pfc. Bradley Manning.

In Mr. Snowden’s case, similar questions are emerging: Why would a relatively low-level employee of a large government contractor, Booz Allen Hamilton, posted in Hawaii for only three months, have access to classified presidential directives or a PowerPoint presentation on Internet surveillance, and how could he download them without detection?

At a White House briefing Monday, Jay Carney, the press secretary, went out of his way not to discuss Mr. Snowden, referring to him as “the individual.” Mr. Carney declined to say whether President Obama had watched a video in which Mr. Snowden explained his motivations and argued that the United States government conducted too much surveillance of its citizens.

American officials cited the continuing inquiry as the reason for the low-key approach. By keeping silent on Mr. Snowden and his case, the Obama administration also avoids elevating his status, even as whistle-blower advocacy groups championed him and his disclosures on Monday. A petition to pardon Mr. Snowden, posted on the White House Web site, attracted more than 25,000 electronic signatures by Monday afternoon.

In a separate case, a federal appeals court ruled Monday against a civil-liberties advocacy group that challenged the constitutionality of the N.S.A.’s warrantless wiretapping program. The Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, based in San Francisco, refused to overturn a lower-court ruling dismissing the lawsuit, brought by the Center for Constitutional Rights.

The suit initially sought to end the Bush-era wiretapping program, and later challenged the constitutionality of new legislation passed by Congress after the original program was disclosed by The New York Times in December 2005.

Michael S. Schmidt and Eric Schmitt reported from Washington, and Keith Bradsher from Hong Kong. Jonathan Weisman and James Risen contributed reporting from Washington, and Richard A. Oppel Jr. from New York.

No comments:

Post a Comment