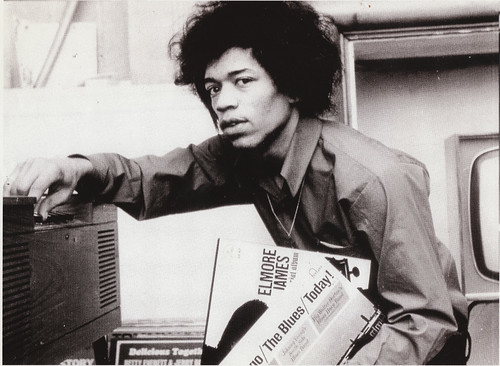

Jimi Hendrix listening to his blues records. His music was heavily inspired and influence by indigenous African American culture. His records continue to sell over 40 years after his emergence as a pop artist., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

Toronto 2013: Andre Benjamin plays Jimi Hendrix in a very novel biopic

By Owen Gleiberman on Sep 9, 2013 at 9:00PM

I’m a sucker for biopics and always have been, but I understand why they’re often thought of as a second-rate form. In a sense, each one is trying to tell two stories at once: the chronicle of its subject’s artistic or political or whatever other worldly achievement (the thing that made us hungry to see a biopic about him or her in the first place), and, at the same time, the private, tumultuous “human drama” of it all. Given that these two dimensions can’t really be separated, and that you have to cram both of them into two hours, it’s amazing, when you think about it, that the best biopics, from Lenny (1974) to Kinsey (2004) to Malcolm X (1992) to Sweet Dreams (1985) to Milk (2008) to Ed Wood (1994) to Ray (2004), are as rich and full and authentic as they are.

Nevertheless, I think that the hyper scrutiny of the “reality” era, when the lives of celebrities (including dead ones) are more subject to exposure than ever before, has made us all a little suspect of the tidiness, the compressions, the convenient fictionalizations, the cut corners that are an essential element of almost any biopic. The good ones are told with more explicitness and authenticity than they used to be, but as a basic form, the biopic now seems cornier than ever. We can see through it, even as we’re hooked on it.

That, I think, is why a new kind of biopic is now emerging: one that doesn’t pretend to tell the entire story of a person’s life, but that focuses, instead, on a key episode of it — a moment at once transformative and defining.

Such a film can move in a lot closer to its subject, can show us, with less panorama but more intimacy and detail (and probably more accuracy), how he or she really operated. It can show us not just accomplishments or incidents but what a life really felt like. In a sense, this style of biopic isn’t new: An early, classic example would be Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), John Ford’s great movie about the early life of our greatest president, played by Henry Fonda. The heart of the movie is a single court case in which Lincoln served as defense attorney back when he was an anonymous country lawyer in Springfield, Ill.

His conduct during the trial — the tactical wiliness, the plainspoken humanity, the ability to work with even ignorant people — becomes his entire life as a politician in microcosm.

That said, I would argue that the new era of biopics I’m talking about really kicked off with Capote (2005), which created such singular and riveting drama out of its willingness to look at who Truman Capote was entirely through the lens of the writing of In Cold Blood. A more recent example of the form would be — yes — Lincoln, which was originally conceived as a much more sprawling, year-to-year biopic, but as Steven Spielberg looked at early drafts of Tony Kushner’s epic screenplay, the more his instinct was: Let’s cut it down to this one chapter and really get it right. And they were right to do it that way.

And now, this year at Toronto, there’s a small, shaggy, very galvanizing biopic that adopts a similar strategy, and it feels like a breakthrough movie. All Is By My Side is set in 1966 and 1967, and it tells the story of the year Jimi Hendrix spent in London, working his way toward stardom. The film ends with Hendrix at the airport, heading back to America to perform at the Monterey Pop Festival — the event that instantly made him a star. But in All Is By My Side, he spends most of the movie as just one more aspiring hippie rock star in Swinging London. This is the first feature directed by John Ridley, the veteran Hollywood screenwriter who, as it happens, wrote 12 Years a Slave (he’s having quite a festival), and Ridley, though he penned this movie himself, has worked hard to give it the feeling of being “unwritten.” A lot of the dialogue sounds semi-improvised, and the whole vibe and tone is less a matter of crystalized dramatic events than of sitting around in clubs and apartments, hanging out and drinking and smoking dope, exchanging a lot of casual, half-heard banter about what’s going down.

If Robert Altman had made a ’60s rock-star biopic, this is what it might have felt life. And that mood, though it can be a bit meandering, creates a fantastic window through which to view Jimi Hendrix.

The ’60s really were about sitting around, and that’s certainly what musicians do a whole lot of the time they aren’t playing.

Beyond that, Jimi Hendrix, though a wild thing on stage, was, is his imperious way, a rather polite and quiet young man who didn’t entirely trust words. He’s played in the movie by André Benjamin (OutKast’s André 3000), and Benjamin nails Hendrix’s soft-spoken, nearly post-verbal demon flower-child cool.

The casting is inspired: At certain angles, Benjamin, with his jutting sculpted chin and elegant cheekbones, looks remarkably like Hendrix, and he captures his distinctive insolence — the seductive smile that can turn into a pout, but always radiating an unspoken mastery and power.

Offstage, there was a feline delicacy about Hendrix, and that’s part of what made his performances so eruptive. It was as if, holding that guitar, which he played like a symphony of danger, he had plugged into some inner electric spirit — had plugged right into God’s amplifier.

The movie is about a little-known chapter of rock history, but Ridley makes it feel essential. All Is By My Side starts in New York, where Hendrix, in processed hair, still calling himself Jimmy James, is playing in dingy clubs as a back-up guitarist when he’s discovered by an unlikely female Svengali: Keith Richards’ 20-year-old British girlfriend, Linda Keith (played by Imogen Poots in what ought to be a star-making performance).

She instantly sees what a virtuoso he is — but what she also registers (and what maybe no male manager type might have) is the extraordinary, leonine sex appeal of Hendrix’s Dylan-as-mac-daddy hipster pose. Fastening on Jimi, she unlocks his mind with LSD, gets him to tease out his Afro, buys him (and even monographs) his first white Stratocaster, encourages him to write and perform his own songs, and keeps telling him what he doesn’t quite know: that his fireworks version of the blues could make him a huge star (especially if he starts to sing). She also falls in love with him. And she introduces him to Chas Chandler (Andrew Buckley), the former member of the Animals who is looking to start a management career. Jimi becomes his first client, and Chandler convinces him to move to London, where everything is happening.

Ridley wasn’t able to get the rights to any of Jimi Hendrix’s songs, so the only songs we hear in the movie are covers. Yet I can’t think of a more perfect example in biopic history of how necessity can be the mother of invention.

It’s not just that Hendrix really was playing covers back then — it’s that we don’t need to hear the sonic crash and burn of “Purple Haze” one more time to experience who he is. And maybe it would just get in the way.

At the historic Saville Theatre concert just before he leaves for Monterey, with two members of the Beatles in the audience, Jimi has only just heard, for the first time, an album that came out a mere two days before — Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band — and when he opens the show with the title track, having taught it to the two other members of the Jimi Hendrix Experience, shaggy-haired Noel Redding (Oliver Bennett) and Mitch Mitchell (Tom Dunlea), in the dressing room only minutes before, it’s a cathartic moment, because it has the playfulness of Hendrix’s ominous audacity (the same quality that inspired him to re-invent “The Star-Spangled Banner”).

The movie is also about how his friendship with Linda gives way to his romance with a feisty redhead named Kathy (Hayley Atwell), and their love/hate bond produces scenes of tenderness and violence. Jimi may adore her, but he knows he’s got more options, and that tears them apart. He’s very clued in to life, but he’s already got the rock star’s addictive selfishness, the quality that would lead to his drug use and death. All Is By My Side — which really could have used a better title — is immersed in the scruffy, privileged street flavor of a budding rock star’s life, and there were moments I wished that Ridley had given the film a little more of a narrative skeleton.

Yet watching it, we feel privileged, too, to be peering in on who Jimi Hendrix was. We don’t get to hear his hits, or to see the greatest hits of his career, but in a funny way the film feels liberated from that burden.

This is a movie made not with obligatory biopic beats but with verve and freedom, and offhand, I can’t think of a better way to honor the genius of Hendrix.

* * * *

You Are Here, the first movie directed by Mad Men creator Matthew Weiner (who I consider a major artist), is a bizarrely misanthropic buddy comedy that pivots around the issue of a family inheritance. Owen Wilson, in charming-weasel mode, plays a hostile, self-centered lush of a weatherman, and Zach Galifianakis is a slovenly angry-hippie basket case suffering from undiagnosed bipolar disorder. The movie has a loud, antic, rather synthetic tone that couldn’t be further from Mad Men, yet there is an overlap: This tale, too, is about people who place layers of addiction and false reality in between themselves and life. The trouble is, once they start to shed their colorful dysfunctions, there’s very little underneath. You Are Here has some squirmy laughs, but not enough of them, and there’s less human dimension to all this than Weiner thinks.

No comments:

Post a Comment