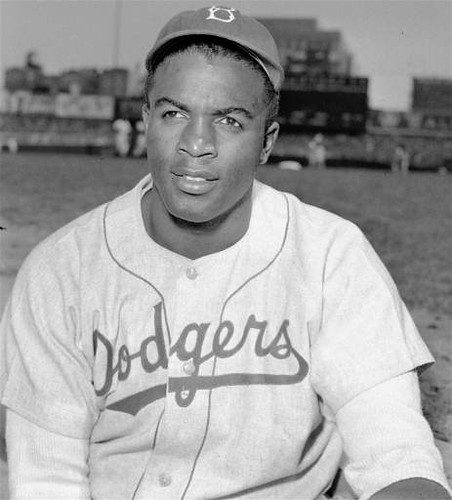

Jackie Robinson was the first African-American to enter Major League Baseball 62 years ago on April 15, 1947 with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Over the last few years the black presence in Baseball has declined tremendously., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

Why are numbers of African-American baseball players declining?

By Mike Herndon | mherndon@al.com

on October 06, 2013 at 11:47 AM

al.com

Hank Aaron. Satchel Paige. Willie McCovey. Billy Williams. Cleon Jones. Tommie Agee.

They are recognizable names -- part of the Mobile area's rich history in the sport of baseball. And they are all African-Americans.

But future lists of baseball greats from the area - or any other in the U.S. - likely will look much different, as African-American participation in the sport has declined sharply in recent years. According to the New York Times, only 8.5 percent of the players on opening-day Major League Baseball rosters were African-Americans. That's compared to 19 percent in 1986, according to the Society for Baseball Research.

Why is the number dropping? It may be because many see a similar decline in the lower levels of the sport, as well.

At Murphy High School in Mobile, one of the biggest high schools in the state and one that carries a relatively balanced racial mix, former baseball coach Bryan Giles estimated that he had 10 black players in his 10 years at the school.

Giles had come to Murphy from Grand Bay and Alma Bryant high schools in south Mobile County, where his teams had enjoyed a better racial mix. His 1997 state championship team at Grand Bay included four black starters - three of which went on to play college baseball. One, Mark Woodyard, briefly played in the major leagues.

Giles attributed part of the reason for this to the difference between rural and urban communities. In rural high schools, students are more likely to play multiple sports - Woodyard, for instance, also played football.

But he also sees the numbers of black baseball players declining across the board, and he's not entirely sure why.

"I wish I knew," he said, adding that it may be as simple as numbers. "I've often thought: You could get two people and they could go out and throw a football or play one-on-one (basketball), but it took more to play a baseball game."

Quendon Montgomery, one of those 10 African-American athletes who played for Giles at Murphy, said it was indeed easier to play pickup games of football or basketball as a kid than baseball. While a pickup game of football only requires a ball and a few friends, and every YMCA and Boys and Girls Club has a basketball hoop, baseball takes more people and, increasingly, more money for equipment.

"Bats are expensive," Montgomery said, adding that his first bat cost more than $150.

"That's a lot of money compared to a basketball you can get for $12 at Wal-mart."

The advent of travel teams, which draw elite young players out of Little League, have also made the sport more expensive, causing New York Mets pitcher LaTroy Hawkins to tell ESPN earlier this year that baseball has become a sport for the rich.

Montgomery added that another reason more black athletes don't play baseball is that many of them don't grow up watching it. The reason they don't watch it, he said, is because there aren't many black players.

"In the Southeast, football is dominant," he said. "We're brought up thinking that the way to make it, a lot of times, is strictly through basketball and football, because the individual talents you have can be shown in those sports. Athleticism is shown more in sports like basketball and football."

Basketball and football are fast games.

Baseball is slow. Basketball and football place a premium on athleticism, which is glorified in shoe advertisements and ESPN highlights. Baseball places a premium on hand-eye coordination and specific skills that are only developed through repetition - hours in the batting cage, hundreds of pitches from the mound.

Because of that, Giles said, kids who don't play baseball at an early age aren't likely to be competitive at it later.

"Somebody asked if I thought I could take the best athlete in the school as a freshman who had never played baseball (and turn him into a player)," Giles said. "My answer was, I think I could make him a center fielder, but I didn't think he could ever hit. I think you could take that same athlete who never played football and turn him into a football player in four years.

"Hitting a baseball is just so hard. No matter how good an athlete you are, it doesn't help you hit a baseball."

Montgomery said he got into the sport because his father, who played college football at Southern Miss, would not allow him to play football until high school. He started playing coach-pitch at age 5 and by the time he reached high school, he was hooked on baseball.

He went on to play at South Alabama and is now a region manager at Dealers Specialties, a firm that collects data for car dealers. There are other African-American players like him who went on to the higher levels of the sport. Former Theodore outfielder Kentrail Davis and former St. Paul's star Destin Hood - a two-sport athlete who was also an Alabama football signee - are now in the minor leagues. Former Alabama Mr. Baseball Pat White of Daphne was a fourth-round Major League draft pick, but chose to play football at West Virginia instead.

But their numbers are declining. Major League Baseball has soug@ht to revive the sport in underserved areas through its RBI (Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities) Initiative, which began by establishing a league in Los Angeles in 1989 and has since spread to 200 cities. Montgomery believes they need to do more.

"You see what the golf community is doing, what the PGA is doing - there's a foundation where they go out into the community, give them equipment, give them lessons - I think something like that is needed," Montgomery said. "If Major League Baseball, in my opinion, gets more involved ... then I think they go somewhere because that's what I really saw in golf."

Of course, golf has Tiger Woods. The most recognizable African-American icons in baseball are retired.

Major League commissioner Bud Selig in April created a 17-member diversity task force to study and address the issue.

Meanwhile, the next Hank Aaron may be out there. But odds are, he's a wide receiver or a point guard.

Bud Selig Purged African-Americans From Professional Baseball

By Luther Campbell Tue., Oct. 1 2013 at 9:00 AM

Alex Izaguirre

Miami New Times

Uncle Luke, the man whose booty-shaking madness made the U.S. Supreme Court stand up for free speech, gets as nasty as he wants to be for Miami New Times. This week, Luke exposes the biggest fail in Major League Baseball.

Baseball fans across the country should be dancing in the streets. Bud Selig is finally going to retire. Last week, Major League Baseball's head honcho announced he is calling it quits after 22 years of driving America's pastime into the ground. He leaves behind a tarnished legacy.

Under Selig's watch, the 1994 World Series was cancelled, Congress investigated rampant steroid use by star players, and the sport has been surpassed by football as the nation's favorite sport. He's acted like a dictator, from denying the New York Mets from honoring heroes of 9/11 on the tenth anniversary of the attacks to forcing the Los Angeles Dodgers into bankruptcy to force a change in owners.

But Selig's biggest failure has been driving African Americans out of Major League Baseball. That should be on his tombstone. When this season began, black players accounted for only seven percent of the opening-day rosters, a historic low. It's gotten so bad Selig put together a 17-member task force, including Hall of Fame great Frank Robinson, to study how to bring back black ball players.

Selig is feeling the heat. He allowed team owners to abandon inner city neighborhoods for the Caribbean and Latin America, where franchises can land players who look and play like Hank Aaron, Vida Blue, Mookie Wilson, Darryl Strawberry, Ken Griffey Jr., Deion Sanders, Kirby Puckett, and other past All-Star African American players.

Unlike the National Football League, Major League Baseball doesn't invest resources and money into developing African American little league and high school athletes. The black Hispanic players are great, don't get me wrong. But professional baseball would be a lot better if there was an equal representation of both in the major leagues.

For instance, University of Louisville quarterback Teddy Bridgewater and Florida State University running back Devonta Freeman started off playing little league baseball for the Liberty City All-Stars, which owns the oldest little league charter in Miami-Dade County.

The All-Stars are part of Liberty City Optimist Club, more widely known for producing future NFL players, but has churned out stellar players on the diamond as well like Lenny Harris, who holds the record for the most pinch hits in a major league career. Teddy and Devonta could have been two-sport stars like Sanders, who also played professional football.

However, Teddy and Devonta ended up playing only football because the NFL has committed resources to helping kids chase their dreams of playing professionally. The Miami Dolphins hold youth football camps and support local high school teams. At Charles Hadley Park, where Liberty City Optimist Club plays, the NFL redid the football field and installed a new irrigation system.

Meanwhile the baseball field is sorely neglected. The city doesn't even water the grass there. Selig and the Miami Marlins have not lived up to their commitment of developing youth baseball programs in parks like Charles Hadley even though Michelle Spence Jones represented the swing vote on the Miami City Commission that approved the team's new ballpark.

If Selig really cared about the lack of African American representation in the big leagues, he would mandate every team support little league clubs and high school teams in places like Overtown, Brownsville, Liberty City, and Miami Gardens.

Selig doesn't need a task force to tell him what went wrong. He is the reason African Americans are not represented in the big leagues.

Follow Luke on Twitter: @unclelukereal1.

Follow Miami New Times on Facebook and Twitter @MiamiNewTimes.

No comments:

Post a Comment