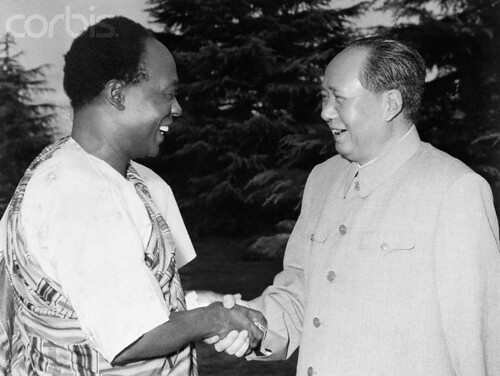

Symbolizing the People's Republic of China's eagerness to win new friends in Africa, Mao Tse-Tung (right) extends the hand of friendship to Ghana's President Kwame Nkrumah at a July 28, 1962 meeting in Hangchow, China., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

Africa can learn from China’s experience

Sunday, 10 November 2013 00:00

Zimbabwe Herald

The development of the People’s Republic of China has been a remarkable achievement in terms of its rapid pace and global impact, and the Chinese experience provides useful lessons for Africa at a time when the continent has attempted several models of development since political decolonisation began in the 1950s.

The current African model of development is the integration of many fragmented post-colonial polities into larger groupings, initially for purposes of economy of scale for trade, investment, and infrastructure development.

The 55 African countries have long acknowledged that with generally low per capita income, vast but untapped natural resources and single-commodity dependence, they cannot individually sustain growth and development within the global economy.

The underlying framework for African integration is rooted in the Pan-African vision of the founding leaders of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), established in 1963 and predecessor to the African Union, established in 2002.

Their vision was to promote unity, solidarity and co-operation among the independent African states while advancing economic development and accelerating the liberation of nations still under colonial rule.

African co-operation has expanded over the past 50 years, resulting in the formation of Regional Economic Communities (RECs), with economic integration agendas based on a legal and policy framework for continental integration and development.

Africa has a huge potential to integrate faster than the current pace because of an inter-play of factors, including a critical mass of human capital currently estimated at about one billion and projected to reach 1,3 billion by 2020.

The continent has the largest mineral deposits in the world in terms of quantity and diversity and, despite being home to the largest number of least developed countries, it is the second fastest-growing economy after Asia, growing at an average 5 percent per annum in recent years.

China went through similar development challenges to Africa before embarking on economic reforms in 1978, and is now ranked second in the world in total trade volume in international trade after the United States, with a literacy rate of over 90 percent, economic growth rate of 9,2 percent (2011), and lower rural poverty.

The Chinese development process was not guided by a single ideology, but is conceptually positioned between a liberal open economy and a centrally-planned model, defined as “socialism with Chinese characteristics”.

Indeed, the instructive significance of the Chinese experience is not the choice of the development model but rather the distinctive ability of the Chinese government to progressively identify constructive and positive aspects of the numerous theories and ideologies tried elsewhere and espouse them into policy plans that can be sustained country-wide over regions and provinces with different natural, economic, ecological, and socio-ethnic diversity.

This should be inspirational for Africa.

Of importance for African integration is how China managed to achieve successful policy co-ordination across the administrative regions, sustain the rapid uplifting of people out of poverty through agriculture and rural development, and put in place infrastructure connecting the regions and provinces.

Another important lesson can be drawn from China’s orderly system that ensures smooth political transitions that are necessary for stability and growth.

It is also important to learn how China attracts and regulates foreign investment to support industrialisation and technological development.

China and Africa share many similar historical, geographical and demographic characteristics.

However, China is a unitary state with more than 1,3 billion people, while Africa is a continent with a one billion population, aspiring to unity and integration of the 55 fragmented economies to achieve economic development and ultimately reduce poverty.

Thus, development in China is co-ordinated while African development is fragmented.

Practical lessons can be drawn to accelerate the African integration agenda at national, regional and continental levels.

The African integration process should be informed by a thorough understanding of five main vectors of China’s development:

Effective policy co-ordination and policy discipline;

Rural development and poverty reduction;

Infrastructural development;

The role of science and technology, education, and research and development; and

Industrial development and export-oriented growth.

The essence here is not necessarily “what” China did (policy specificity), but real focus should be on understanding “why” they did it and “how” it succeeded.

China’s success today is largely due to the nurturing of a visionary and dedicated leadership system based on an orderly political system; capable and competent bureaucracy; effective policy planning and co-ordination; and policy discipline.

Other factors include a commitment to agriculture and rural development for poverty reduction; strategic engagement and utilisation of FDI for cross-sector development; infrastructure development; export-oriented industrialisation; and active engagement of research-oriented think tanks in policy formulation and implementation.

China successfully administers development policy over a very expansive polity, which is similar to Africa by historical, geographical and demographic comparison; but Africa grapples with co-ordinating regional integration processes with little economies that are weak and fragmented.

The accelerated socio-economic development in China is generally regarded to have its historical foundation in agricultural sector reforms, with poverty reduction an important goal of national development.

China’s sustained high economic growth and increased competitiveness in manufacturing was underpinned by the massive development of physical infrastructure.

This presents useful lessons to Africa.

China’s success in providing quality infrastructure across the regions is due to three key factors: high-level government commitment; a state-guided and effectively decentralised planning and co-ordination framework; and a robust framework for monitoring and evaluation.

The success of China’s industrial development can be attributed to gradual and strategic economic liberalisation, an effective policy of foreign direct investment, incentives to both private and public sector enterprises, strategy of internationalisation for state-owned enterprises, research and development, and dynamic state institutions for policy guidance.

Success is driven by: China’s strategic balance of protectionism and economic liberalism; China’s FDI policy and the regional development policy; and export-oriented growth and foreign economic policy.

Education combined with research and development has consistently been central to China’s development policy, complemented by science and technology education and development interventions.

Deng Xiaoping, who initiated reforms in 1978, was very clear on this, saying, “We should make every effort to develop education, even if it means slowing down our efforts in other sectors.”

China adopted strategies to intensify research and development with the aim of ensuring to adopt and adapt new technological innovations to drive development.

Success was driven by two key strategies:

Science and technology education; and

Research and development.

The development of China also owes its success to the immense contribution of policy research institutions, or think tanks, to policy formulation and implementation.

Think tanks in China play a role in bridging the gap between knowledge and policy through extensive research and analytical work.

The Chinese government’s engagement with think tanks is different from African countries where there is very little interaction.

Africa can borrow insightful lessons from the way that China acknowledges and incorporates the role of think tanks, maintaining a close working relationship and incorporating their findings into public policies and national development plans.

The Chinese development experience was a result of comprehensive reforms whose success depended on the effectiveness of the Chinese government, institutions and citizens to co-operatively plan and co-ordinate the cross-sectoral interventions throughout all the provinces and regions.

Several recommendations can be offered on how aspects of the Chinese experience can be harnessed by Africa and by African Regional Economic Communities and countries to identify, frame, co-ordinate and implement their regional integration plans, policies, programmes and projects, and to effectively benefit in this regard from the opportunities generated through increasing co-operation and collaboration with China under the Forum on China Africa Co-operation (Focac).

Lessons from the Chinese experience must be subjected to an in-depth analysis through a three-pronged incremental probing approach so as to determine their suitability, feasibility, practicability and acceptability within the African context.

The incremental probing would entail questioning why an intervention was made, how it was implemented, and what impact it had.

Of importance here is how China did it given the vast expansive nature of its polity and population, as well as regional diversity and autonomy.

Lessons for African integration must be based on African realities, just as Deng Xiaoping was very clear that lessons for China must be rooted in China:

“In carrying out our modernisation programme, we must proceed from Chinese realities . . . we should learn from foreign countries and draw on their experience, but mechanical copying and application of foreign experience and models will get us nowhere.”

The lessons learned draw on the main vectors of Chinese development experience.

Africa can draw lessons from five main areas of Chinese development to expand and accelerate continental integration through:

Strengthening regional policy planning and co-ordination mechanisms;

Harmonising regional agricultural policies and reforms to boost productivity;

Negotiating joint partnerships for construction of trans-boundary infrastructure;

Attracting high-technology investment through joint ventures to allow value addition for export competitiveness and increase the value of exports; and

Strengthening the linkages between research institutions and policymakers.

This article was adapted from a key paper delivered at the China-Africa Symposium hosted in Harare from 22-24 October by the Southern African Research and Documentation Centre (Sardc) and the Chinese Embassy with support of the Forum on China Africa Co-operation.

No comments:

Post a Comment