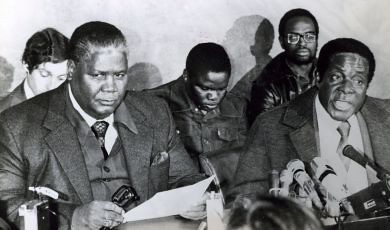

Joshua Nkomo of ZAPU and Robert Mugabe of ZANU, leaders of the Zimbabwe liberation struggle. This photo was taken during the revolutionary war to liberate ZImbabwe during the 1970s., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

Tribal Nomenclature an affront to national unity

December 17, 2013 Opinion & Analysis

Zimbabwe’s provinces could sensibly be renamed using historical, national or geographic criteria

Tichaona Zindoga Senior Political Writer

Zimbabwe Herald

There are some anachronisms that apply to Zimbabwe today that should not only be surprising but also embarrassing, at best, and at worst an indictment on Zimbabwe’s sense of unity and self-determination Take for example the issue of colonial names that continue to define the country’s provinces: we have Mashonaland, Matabeleland and Manicaland. These names define the regions as “land of the Shona people”; ‘’land of the Matabele (or Ndebele)’’ and/or ‘’land of the Manyika’’.

Mid-17th century Greeks had a word called “anakhronismos”, whose etymology was “ana-“meaning “backwards” + “khronos”meaning “time”. An adoption of the word into English gave rise to a word known as “anachronism”, which is defined by the Merriem Webster

Dictionary as pertaining to a person or a thing that seems to belong to the past and does not fit in the present.

Anachronisms happen all the time; everywhere, and in a movie or novel a word, object or event that is mistakenly placed in a time where it does not belong is called an anachronism.

There are some anachronisms that apply to Zimbabwe today that should not only be surprising but also embarrassing, at best, and at worst an indictment on Zimbabwe’s sense of unity and self-determination.

Take, for example, the issue of colonial names that continue to define the country’s provinces: we have Mashonaland, Matabeleland and Manicaland.

These names define the regions as “land of the Shona people”; ‘‘land of the Matabele (or Ndebele)’’ and/or ‘‘land of the Manyika’’.

These names exist 33 years after Independence and 26 years after the historic Unity Accord which was signed on December 22 to end a civil war that had strong tribal characteristics.

Zimbabwe became one, as shown by the embracing leadership and the liberation war parties PF-Zapu and Zanu-PF that united to form a singular Zanu-PF.

Tribalism should have gone away.

Regionalism should have gone away.

So should have the names that define the same whose continued existence is really a sin against national unity.

The names may have been appropriate in an era of colonialism, which the racist system thrived on to divide the people and tribes, and often playing them against each other.

The effect of this has been a sense of inaccessibility or lack of entitlement of people who move to the other regions.

This is even discernible today, when one feels alien in Bulawayo if they come from Manicaland or Harare.

They feel that as Mashona or Manyika, they do not belong. Where is the nationalism and nationhood?

A close kin of this sin against national unity is the deliberate language barriers that the authorities have decided to perpetuate by keeping a system where indigenous languages are taught according to region.

Shona is for the so-called Mashonaland, Manicaland and Midlands, while Ndebele is officially the language for the children of Matabeleland.

And ironically, English is universal.

Who does it serve when black people cannot communicate in a common black language in their own country?

Some people take offence when they hear someone talking the language of another region.

It is unfortunate because the universalisation of local languages, that is the teaching in the country’s schools of the indigenous languages, should help foster national unity. It also enhances national development and peace.

Language is said to be the carrier of culture, and a nation that shares common languages certainly will be rich and defined in terms of culture.

As people often decry colonial borders and how they marked out African peoples, it is really surprising how after Independence these names have been retained.

A sensible approach will be to rename the provinces — and this should be a matter of now — and use more historical, national or geographic criteria.

The historical approach would see the country’s provinces being named after historical events and personalities that are relevant to the area.

If, for example, the country feels so indebted to historical figures and luminaries, is it out of order to name provinces after the likes of Tangwena for Manicaland; Nehanda for Mashonaland West; Lobengula for Matabeleland or Kaguvi for Mashonaland East, etc?

A Harare province, if demarcated, could be called the Mbari province in honour of the historical people of the city. Geographically, provinces could be named after landmarks and the physical location of the region.

Hence, Masvingo is appropriately named after the Great Zimbabwe Monuments from where the country got its name. Why not for, Matabeleland, Matobo province in recognition of the historical Matopo Hills?

The Midlands province is sensibly named for its location.

Mashonaland West could be Kariba province or simply the Great Dyke.

There is need, however, for uniformity in the naming of provinces so as to project a sense of order and consistency.

It will be also useful to look at other countries that have names for provinces as offending as ours.

South Africa, thankfully, does not have a Zululand or Xhosaland but has nine sensibly named regions.

These are Western, Eastern and Northern Cape that are named after the historical and geographical cape where the old Cape of Good Hope and today’s Cape Town are.

(A cape is defined as headland or promontory of large size extending into a body of water, usually the sea; and this geographical fact makes the name of the Cape province appropriate.)

North West is geography.

Free State is historical.

Limpopo is geographical as is Gauteng, which means “place of gold”.

Perhaps the odd one out is KwaZulu Natal, which connotes tribe.

Rwanda made the naming of provinces simpler and concise. It only has Eastern, Southern, Western, Northern and the metropolitan Kigali City.

It cannot get simpler than that, and moreso it does not offend or carry innuendos of division.

As the country observes National Unity Day on December 22, it will be instructive for authorities to disabuse the country of names and practices that connote disunity and division.

Zimbabwe does not need such anachronisms.

No comments:

Post a Comment