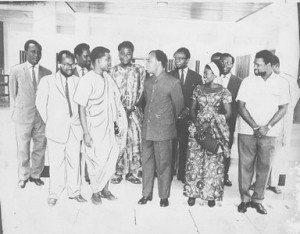

President Kwame Nkrumah and the Ghana Association of Journalists. Ghana under Nkrumah's Convention People's Party government published numerous revolutionary newspapers and journals. Ghana Television was first directed by Shirley Graham DuBois., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

African Journalists Conference

OPENING OF THE SECOND CONFERENCE OF AFRICAN JOURNALISTS

November 11, 1963

On behalf of the Government and people of Ghana, let me welcome you, journalists of Africa, and all those who have come here to attend this conference.

It is not simply out of courtesy that I am here to open this Conference of African Journalists. Most of you will know that I come to speak to you with a particular sense of pleasure as an old journalist who can still be excited by the smell of the printer’s ink and the clatter of the printing machine.

If we interpret journalism as the dissemination of news and the clarion to action, then journalism is certainly not new to Africa. From time immemorial, we have developed our own special system of transmitting news and messages across the country, from village to village, from community to community; we have devised our peculiar means of gathering our people together and putting problems before them for decision. The talking drums and the courier have been the harbingers of news.

From the days of the drum, we have accepted as an inexorable canon that the news which was transmitted should be true and the information conveyed accurate and reliable. For, the safety and the lives of many people might depend upon it.

In these modern days, we have the teleprinter and the telex machine for conveying news at greater speed. But the principle and the purpose of it all remain the same. Even while the drum spoke, we in Africa were developing more modern forms of journalism.

Indigenous newspapers in West Africa have at least a hundred years of history behind them. In 1858, only fourteen years after the Bond of 1844 and before the Gold Coast had been annexed as a definitive colony of Great Britain, the West African Herald was edited by Charles Bannerman, a son of the soil. About the same time, John Tengo Jabavu was editing the IMVO in South Africa. In Nigeria, the basic ideas of modern nationalism were developed by John Payne Jackson from 1891, in his journal, The Lagos Weekly Record.

James Brew in the Gold Coast of the 1870’s and 80’s, and J. E. Casely Hayford, a generation after, edited local nationalist papers; but they were restricted in their circulation to the few literate readers along the coast.

The astonishing thing about these editors and their small band of journalistic collaborators was how they managed to build up a secret intelligence and news gathering service along the coast, which involved, beside the normal hazards of anti-colonialist activity, the -danger of some of them finding a premature watery grave. In those days, there was no proper road between Cape Coast and Accra — not even the rough one we knew before the Government of the Convention People’s Party built the present modern ones. So the editors and their co-workers worked their clandestine way by canoe along the coast to the capital, Accra.

There they ferreted out all the latest materials that could be used against the colonialist government, and then they paddled their dangerous way back to Cape Coast. All these activities were done at night. It was always a puzzle to the British administration in Accra as to how these newspapers were able to appear in Cape Coast with such "hot" news so quickly.

Nevertheless, these and other journalists did much to spread the doctrine of equal rights for Africans, especially as schooling began to widen out gradually and we were becoming conscious of ourselves as political beings.

In North Africa, in 1930, L’Action Tunisienne was launched by Habib Bourgiba, now President of Tunisia, and a group of his Neo Destour party members. In the Ivory Coast in 1935, the journal L’Eclaireur had an immense success in African circles. It led a campaign against reactionary chiefs and colonialist oppression. It demanded measures of social reconstruction and urged the cause of the unemployed and of the African farmers, who had been hit by the colonialist — made economic crisis. Nnamdi Azikiwe’s West African Pilot and the organ of the Convention People’s Party — the Accra Evening News in more recent years, led in the field of nationalist journalism. Wallace Johnson of Sierra Leone, with his West African Standard, did some ground work in trade union journalism. The Africanist emerged as the custodian of South African nationalism in 1953 and remained a revolutionary mouthpiece of the Africans of South Africa. Its founder and first editor was Managaliso Sobukwe, President of the Pan-Africanist Congress of South Africa, who is now detained indefinitely on Robben Island after serving three years’ imprisonment for his part in the cause of freedom.

George Padmore, working outside Africa, but identifying himself completely with its struggles, carried on almost all of his adult life a tenacious fight for African nationalism and independence. His contributions to the press of Africa and to that of peoples of African descent in the West Indies and the United States; his widespread journalistic writings throughout the world, served as rallying point and inspiration to the leaders of African independence and the masses.

The African press, born of incipient nationalism, nurtured on political consciousness, and developed side by side with a growing sense of responsibility, is now strong and healthy, despite the many obstacles placed in its way. However, the fact that the press in Africa today is an important and influential institution, does not alone lend importance to your meeting today.

The special significance of this gathering is that, it is the first conference of African Journalists since the Organisation of African Unity was established at Addis Ababa in May this year. As such, it can do nothing less than fulfil the purpose of a continental press conference on the Unity of Africa.

As a professional man, the African journalist shares with other journalists throughout the world, the duty of gathering information carefully and of disseminating it honestly. To tamper with the truth is treason to the human mind. By poisoning the well-springs of public opinion with falsehood, you defeat, in the long run, your own ends. Once a journal gains a reputation for even occasional unreliability or distortion, its value is destroyed.

It is part of our revolutionary credo that within the competitive system of capitalism, the press cannot function in accordance with a strict regard for the sacredness of facts, and that the press, therefore, should not remain in private hands.

As, in a capitalist or neo-colonialist environment, profit from circulation and advertising is the major consideration, the journalist working within it is caught by its mechanics.

No matter how great his personal integrity, as long as he remains, he must mould his thinking to its dictates. Consciously or unconsciously, he is forced into arranging news and information to fit the outlook of his journal. He finds himself rejecting or distorting facts that do not coincide with the outlook and interest of his employer or the medium’s advertisers. Willy-nilly, he adjusts his ideas to that of the class which his journal represents, the class for which it caters, the interests and objectives which it serves to advance.

Under the pressure of competition for advertising revenue, trivialities are blown up, the vulgar emphasised, ethics forgotten, the important trimmed to the class outlook. Enmities are fanned and peace, is perverted. The search is for sensation and the justification of an unjust system in which truth or the journalist must become the casualty.

It is no wonder, then, that for every decent or well-informed journal in a capitalist country, you have many more of the kind that concentrates on sensationalism and scandal; that cover up facts or, deny them; that manufacture news in order to mislead and corrupt. There are journals that employ special techniques of presentation in order to ensnare the minds not just of thousands, but of the millions that read them. Every means, both subtle and raw, are used to maintain sway over the minds of men, and thus secure and hold their support in the continued exploitation and suppression of the oppressed. Often they are led to concur in their own exploitation. They are enjoined against peace, they are manoeuvred against freedom and right.

Unfortunately, some of these journals have made their way into our continent and are employing their influence to wean our people to ideas and ways of life that run counter to our image and our hopes. We must be vigilant against their penetration and their incitement. We must be careful not to take their falsities as models, either for our public or our journalists. For our African journalists have; different task, a higher responsibility, a greater objective, which demand a mould of quite another order.

In Africa today, three types of African journalists can be recognised on our continent. There are those who are purposefully and unreservedly devoted to the cause of the African Revolution. Such journalists are dedicated to African freedom, African progress, an African unity.

Then, there are those who by their work serve only the interests of private capital. These journalists have no minds of their own, no devotion to their people or their continent. They carry out the dictates of their foreign employers operating in Africa; they gyrate in the effort to anticipate their masters’ wishes.

Thirdly, there are those journalists who, unwittingly, or deliberately, serve the interests of foreign governments by their support of the client and puppet regimes that have been established in Africa.

The last two categories wrap their distortions and their diversions from the truth in a morbid appeal to chauvinism, unreason and latent animosities.

Whether they are aware of it or not, they are misusing their talents and their opportunity in the interest of Africa’s enemies and against those of our people, our continent and our cause. We who are fighting against colonialism and imperialism, we who are lighting against the blandishment of client states and settler governments in Africa, and are seeking to create a just society in which the welfare of each shall be the welfare of all, must stand against the methods of those whose journalism has precisely the opposite ends. We have nothing to gain by suppressing or distorting facts. Circulation of itself is not our first consideration; though obviously, we are anxious to reach and inform the widest possible audience. But we have no wish to play upon the gullibility of that audience, for it is precisely to the interests of that audience that we are dedicated. And we can only promote those interests by self criticism and the faithful presentation of truth and fact.

The journalist who works faithfully for our African Revolution refuses to sell his soul to imperialism and to Moloch, and thus starts with an advantage over his colleagues of the imperialist and neo-colonialist press. His integrity, as long as he persists in this decision, is assured. To the true African journalists, his newspaper is a collective organiser, a collective instrument of mobilisation and a collective educator — a weapon, first and foremost, to over-throw colonialism and imperialism, and to assist total African independence and unity.

The true African journalist, abjuring imperialist blandishments and bribes, can certainly call his soul his own. His work may be more difficult because of deficiencies in the technical means of gathering information and the daily harassments that confront him; his remuneration may not be great and expense accounts non-existent. But he has other more satisfying rewards. He draws contentment from an honest job honestly done. His satisfaction is in his integrity, in work performed for the betterment of his fellows and the society of which he is a worthy member.

He does not need to peep through keyholes for scandals, or bribe underlings to divulge what should remain private and personal; he does not need to concoct for manufacture exciting revelations. He is not forced to doctor news and debase public standards to fit the purpose of the rich and the public would — be richer. I am reminded here that a British journalist friend of mine once told me that sometimes, the news items he sent to his paper in London were so doctored that he had difficulty in recognising what he himself had written. The true African journalist very often works for the organ of the political party to which he himself belongs and in whose purpose he believes. He works to serve a society moving in the direction of his own aspirations.

How many journalists of the imperialist and neo-colonialist press have this satisfaction? How many know this peace of mind? How many work with respect for their calling, and with faith in the society which they serve?

These are high rewards for an honest man in the course of his professional career. But they are not earned without corresponding responsibilities. Every African is responsible to the African Revolution by the heritage of his birth and by his experience of colonialism and imperialism.

The responsibilities of the journalist come particularly high in the hierarchy of our revolution; none higher, none more onerous, none more satisfying than those of an African journalist using his talents and his integrity in adverse and sacrificing conditions, not only in the cause of the freedom and independence of his country, but in the wider cause of the political unity and cultural and material development of the African continent, of which his country is a part.

Truth, we say, must be the watchword of our African journalists and facts must be his guide. These tenets, however, must not excuse dullness in our newspapers and our journals. They must not be used as a cover for shoddy writing and ambiguous intentions.

The African journalist is not only expected to communicate the facts and aims of our African Revolution, but to do so compellingly and without fear. He must continually and fearlessly expose neo-colonialist subterfuge. He must attain a proper understanding of the African Revolution, its purpose and its travails. He must acquire technical proficiency and literary skill.

Even though he tells the truth, it does not make the same impact when presented in a dull manner with vain repetition, as if without conviction.

We must make our publications attractive to the eye and easy to handle and read. We cannot self-righteously or contemptuously dismiss the appeal or under-rate the seductiveness of the brightness in which the imperialism clothes its journalistic offerings. Bright colours and gay forms are used to cover insidious suggestiveness. We have more genuine fare to offer, but we would be foolish to dismiss airily the blandishments that cover their frivolities and poisonous intentions. We would be deceiving ourselves if we were to under-rate their abilities and their determination to penetrate deeply into our midst and draw our people away from their own true interests.

Africa presents a vast market for popular magazines, especially the smart magazines which cater for the faster juvenile and middleclass Afro-Americans, anxious to share in the fruits of the rich material environment so near and yet so far from their reach. Our enemies are intent to make these the thin edge of intellectual neo-colonialism.

You will not beat the spurious and seductive output of Western journalism except by publications of high quality and popular appeal. The answer is not to copy them, but to excel them — to educate the taste of the African reader to the point of rejecting the undesirable foreign wares.

To do this, however, you must understand our Revolution; know its mainsprings and its objectives. You must know what spirit we have to import, what kind of society we are seeking, what nature of, men and women we hope to fashion. The facts you gather must manifest Revolution foster its clan and depict truthfully its progress, its pitfalls and obstacles. They must encourage our people and not deceive them with false hopes or false achievements.

You have the duty to express the views which will move our Revolution forward. For all of this, the ordinary professional education of a journalist is not enough. You must understand the relationship between the press and our society and you must understand our society in relation to the rest of the world.

The truly African revolutionary press does not exist merely for the purpose of enriching its proprietors or entertaining its readers. It is an integral part of our society, with which its purpose is in consonance. Just as in the capitalist countries, the press represents and carries out the purpose of capitalism, so in Revolutionary Africa, our Revolutionary African press must present and carry forward our revolutionary purpose. This is to establish a progressive political and economic system upon our continent that will free men from want and every form of social injustice and enable them to work out their social and cultural destinies in peace and at ease. This is what we are trying to do here in the Ghana o School of Journalism.

For our continent to develop along these lines, we must repel a host of enemies. Enemies whom we call imperialists, colonialists and neo-colonialists, in an attempt to categorise their activities, but enemies whose ends are always the same: the undermining and restriction of our independence. They work laboriously to impede and frustrate our economic development; they employ all manner of means to prevent our unity as a continent. To destroy our political stability is the obvious method of attacking our independence.

Hence they try to corrupt our political institutions, our civil service, our police, our army. Even our universities and judiciary are not exempt from their attempts to capture our constitution for their own ends through bribery and corruption. But thanks to the firm resistance at all levels of our national movements, they are often foiled.

A more effective method of destroying our political stability is to intensify our poverty so that popular dissatisfaction will infect our states with treason and violence. The legacies of poverty and backwardness, left by the colonialists and which can be removed only by great sacrifices spread over long periods, offer fertile fields for such intrigue.

We have seen enough to know that the imperialists use decolonisation as a manoeuvre for the greater exploitation of their former colonies. They do not accept it as a historical necessity to end a shameful and untenable period in human history. In the face of stormy winds of freedom blowing through Africa, the colonialists have only veered their course; they have not changed it. Where once they ruled by force, they now manipulate to maintain their hold (on Africa) by cunning, bribery and subterranean violence. Ironically, they follow in the footsteps of the early Portuguese explorers, who first named the southern tip of our continent the Cape of Storms, and then changed the name to the Cape of Good Hope. The change of name could not change the weather conditions; and did no more for the indigenous inhabitants than to make that comer of Africa a hell on earth for them.

If the imperialists have been forced by circumstances to cede independence to former colonies, we know by now that the intention was to make that independence purely nominal. Wherever independence aims to become a reality, the hostility of the imperialists knows no bounds. This ulterior intention has resulted in dividing Africa into client states and states whose independence hangs by a thread. As colonialism vanishes away from Africa under the blows of Freedom Fighters, neo-colonialism is raising its head as the greatest threat to our freedom and progress.

What is neo-colonialism? It is the situation we find in a country where a colonial power grants nominal political independence to a territory, but sees to it that the control of the economic arrangements of the territory are still in the hands of the ex-colonial power; which is thereby able to dominate its economy and, indirectly, the state apparatus. It is empire building without the flag.

And this is how it works:

They see to it that the political power remains in the hands of indigenous reactionaries.

They manoeuvre to control the Army, the Police and even the Intelligence Services.

They see to it that the economic institutions of the country are in the hands of their agents, and that economic production is completely controlled by private foreign capital leaving only the less profitable infrastructure in the hands of the indigenous population.

They divide the Trade Union and other popular movements. When they have gained full control, in this way, of a client or puppet state, with a client or puppet administration, then they are in a position to do what they like to the territory, its government and its people.

If they cannot get their own way, then they engineer political and military coups, to overthrow the regimes and install new reactionary regimes which will carry out their orders.

Some of us allow ourselves to be used as agents of such neo-colonialist and settler government espionage systems operating in Africa. Even the Fascist Regime of South Africa could have agents among us here.

I have always been particularly proud of my trade union associations. As a worker in my student days in America, l belonged to the Maritime Workers’ Union and played an active part in our struggles to better the living conditions of our fellow workers.

From the very early days of the African resistance struggle, trade unions have played a dominant role in the conquering liberation movements. That is our experience in Ghana, and l know the experience throughout the other African countries.

Throughout this vast continent of ours, workers organised or unorganised must become aware of the duty they owe, not only to their own country, but to mother Africa and must rapidly adjust themselves to the new role of nation building and also guard jealously our independence against incursions of neo- colonialism. African workers must organise themselves for the final overthrow of colonialism and liquidation of neo-colonialist or neo-colonialist exploitation. The journalists of Africa must recognise this and use the African press in supporting our trade unions and exposing the evils of neo-colonialism.

My faith in the All-African Trade Union Federation as the most positive and reliable ally in our struggle against neo-colonialism is an abiding one. AATUF must have the unconditional support of the African Press as against the other neo-colonialist trade union groupings in Africa, either of ICFTU or those who serve as vehicle of neo-colonialist infiltration. Our African journalists must help explain the importance of trade unions in our African revolution. The African trade unions are those that have their roots in the broad mass of our people. They must be in a position to bring to our attention quickly, the feelings of the workers and we must draw them into consultation on the formulation of Government policy. There cannot be any conflict of interest in the task of nation building. It must be the responsibility of the African Governments to encourage our trade unions and help them consolidate their strength.

To build Africa which must be Africa liberated from exploitation, Africa just and strong, we must build with the people and for the people. Africa must win through to real independence; and the only road open to us is the one whose first station was the Summit Conference of Addis Ababa. We must now press on quickly to a Union Government of Africa.

Those who say that a continental government of Africa is illusory are deceiving themselves. Worse, they are deceiving their people, who see in the unity of our continent the way to a better life. They ignore the lessons of history. If the United States of America could do it, if the Soviet Union could do it, if India could do it, why not Africa?

And it needs to be done now. No useful purpose is served by putting it off. On the contrary, recent events have shown that delay can only exacerbate our divisions and make our coming together more difficult. We want the widest economic and social development, and we want it as soon as possible. We can get it, and get it quicker, only by planning it on a continental scale. And it becomes more and more obvious that continental planning cannot precede but must emanate from a continental government of Africa. It is this recognition that directs our enemies and detractors to keep us divided.

An All-African High Command is an immediate necessity, so that we can be ready at all times to protect our sovereignty and our independence. Otherwise, we will fight among ourselves, and destroy all we have so far achieved, to the delight and advantage of the neo-colonialists.

Only a continental government of Africa will give reality and purpose to African Unity. Without it, African Unity will remain an empty and sentimental slogan.

How can we hope to stop France from continually testing atom bombs in the Sahara? Only a Continental Government of Africa can make de Gaulle’s France pause to reflect. No resolutions or charters can hope to do this. A continental government for Africa, backed by a continental army under a unified High Command, would have authority to keep the peace throughout Africa. It would close the road now wide open to a neo-colonialist take-over in Africa.

The Moroccan-Algerian border dispute which erupted into open warfare last month, and others like it, presents a grave symptom of our desperate plight as independent states. Among the colonial legacies which imperil our present and our future, there is the uneasy condition of ill-defined boundaries between states which hug a nationalist passion and new-found independence. What can more easily lead to strife, conflict and war?

With all the goodwill and wise leadership in the world, these border disputes cannot be permanently settled. Especially when they have their origin in the criminal colonial scramble for Africa. Why visit the sins of colonialism upon the children of the African Revolution? Why should we pay for-the sins that colonialists have committed against us? The only solution to such border disputes lies in the establishment of a Union Government of Africa in which we shall all enjoy a common union citizenship which will make boundaries melt away.

We were divided on our continent not by chance or by choice, but by force. We cannot cure that division by force among ourselves. We can only cure it by African unity, by coming together within a union government, not by perpetuating the artificial boundaries between us.

In the face of the assaults which neo-colonialism is now making on the whole of Africa, and the preparations for war in those parts of Africa still occupied by the imperialists, the dividing line between triumph and disaster for African unity surmounted by a continental government is very thin. The military coups and plots, the border disputes in independent Africa do not help to correct this situation.

We have allowed the neo-colonialists to intimidate us and make us afraid to move on to a continental government in Africa. While we listen to their counsels about the difficulties and the inopportuness; while we allow them to convince us that there are too many differences between us; while we permit them to assure us that we can only prosper by being strung to them and not to ourselves; they I are getting on with their plans to drive us further and further apart and deepen the fits between us.

Time is being used by them to sow confusion and destruction among us. We can frustrate their knavish tricks only by coming together, by coming together now. Putting off the reality of African Union will only add inertia to the confusion, it will bring the African revolution to a standstill, perhaps for the next thousand years. Now is the hour to seal the Union Government of Africa.

This is the Africa which you, as African journalists, must help to create and develop, the new Africa of which our people dream, for which they stretch out their hands. With your brains and your pens, with the strength of your faith and the passion of your thoughts and words, you are the vanguard of the crusade for a United Africa. Never sell yourselves for a mess of pottage, never allow yourselves to be bought.

Less than six months have elapsed since Addis Ababa and, as l said the other day, the course of events has already overtaken us. We must take care that it does not overwhelm [us completely. lf there has been an ebb in the full tide of continental unity which launched the Addis Ababa Charter, we must attribute it to pressure on the client states and to a general stepping up of imperialist intrigues and threats throughout Africa.

Let us, for example, take the Congo that large and rich state in the heart of Africa as the yardstick by which to measure whether we have progressed or not since the Summit Conference. If we look closely, we will see no progress, but rather a slackening of the high resolves and practical measures which we enunciated at Addis Ababa.

The situation in the Congo approximates that which found the Latin American states engulfed in political and military coups by juntas in the pay of outside interests and the control of foreign intelligence agencies.

The Belgian exploiters return in droves, secure in the knowledge that Mobutu’s army is the only source of governmental power, and that he will protect them if the people’s fury erupts. American and Belgian capitalist have now resolved their differences in the Congo, whose wealth they mean to exploit as joint partners once a military dictatorship has broken completely the Lumumbaist political forces and the resistance of the industrial workers.

The writing on the wall for the Congo is as plain as it was in Peru, as it was in the Dominican Republic and in Honduras • as it was in South Vietnam before the military junta took over in order to give the war against the people of Vietnam a new lease of life.

The plight of the Congo is no secret in Africa. Lt is known in the fullest detail in every part of the world. What will happen if we allow the Congo Republic to go the way of a Latin American Republic? We shall do no less than give the green light for the consortium of imperialists now operating in Africa to go ahead with plans for the structure of neo-colonialism here on the Latin American model.

If we let go the Congo, it will strengthen the colonialists and the settler-government of Southern Africa. It will mean the handing over of the struggle of our brothers in Northern and Southern Rhodesia and in South Africa and the Protectorates to the more ruthless persecution of the practitioners of apartheid and quasiapartheid. It will give encouragement to Verwoerd and his allies to strengthen still further, the army that is being built up in South Africa.

This is the time we should be getting together to coalesce our forces against the threat of apartheid, South Africa’s menace to our African independence. We would be foolish, if we sit back calmly while South Africa’s ground to air missile base endangers our very existence.

If we let go the Congo we shall reinforce neo-colonialist presence here in Africa. While we are dilly-dallying, they are getting busier and busier on our continent. Western Powers are increasing their investments in South Africa and refuse to be deflected from their support of Verwoerd and his regime. Surely, these are signs of imperialist strength, and unity, while we demonstrate our divisions and our feebleness.

If we let go the Congo, we shall nullify the Addis Ababa Charter and confuse our minds with the hope of a unity that will never be fulfilled. We shall hand to neo-colonialist an instrument that will help them rather than the unity of Africa. The Congo is a symbol to all of us. And what goes on there now may be a symbol of what can happen to Ghana, Nigeria, Guinea, Mali, Tanganyika or any other African state.

It is against these manoeuvres of the imperialists and neo-colonialists, that the African journalist must be vigilant. He must shout for all the world to hear, and place on it the responsibility for thwarting their designs against Africa. The African journalist must be just as vigilant against our own faults and defections; and against our dilatoriness and unwillingness to make a reality of African unity. His is the duty to guard our African Revolution and see that it moves forward in the right direction. He must speak out, no matter the cost. His columns must vibrate with the call to the African nations to take up the challenge that the African Revolution poses.

The African Revolution has, for the most part, adopted one-party rule as its most appropriate political instrument for ending tribalism and planning development within the democratic framework of our African society. Even if we wanted it, we could not afford the deferment of strong and immediate governmental action which class and party politics entail. We cannot afford the political luxuries of capitalist democracy. We have neither the capital nor the time.

The multiplication of political parties in Western Europe has not prevented the enthronement of dictatorial powers in some countries nor political instability in others. We see the Executive of the United States constantly frustrated over its measures to end racialism and to introduce social security legislation. What can go on there for decades, without a political breakdown, would bring chaos and disaster within a short time in any African state.

That is why Ghana has chosen the way of peoples’ socialist parliamentary democracy. We are aware that the one-party system cannot function in an environment contained by restrictions of a client or a neo-colonialist state. We have also chosen the path of socialism for our economic reconstruction, because we believe that it is the only way to liquidate the remnants of colonialism. We believe that it is the only sure way, and the quickest, to build a happy life for the masses of our people.

Unless Africa embraces socialism, it will move backward instead of forward. Under any other system, our progress can only be slow. Our people will lose their patience. They want to see progress, and socialism is the only means that will bring it speedily. Congo Brazzaville and Dahomey are object lessons for us. The attempt to enforce a one-party system in a non-socialist environment can lead only to disaster.

Because we want strong and yet democratic governments in our African Revolution, we must guard against the dangers inherent in governments whose only opposition to tyranny and abuse lies in the folds of the ruling party itself. A ceaseless flow of self-criticism, an unending vigilance against tyranny and nepotism and other forms of bribery and corruption, unswerving loyalty to principles approved by the masses of the people, these are the main safeguards for the people under one-party rule.

Who is best able to exercise that vigilance, to furnish the material for self-criticism, to sound warnings against any departure from principles, if not the press of Revolutionary Africa?

The African press has a vital part to play in the revolution which is now sweeping over the continent. Our newspapers, our broadcasting, our information services, our television, must reach out to the masses of our people to the workers, the farmers, the trade unionists and peasants, to the university students, the young and the old - to explain the meaning and purpose of the fight against colonialism, imperialism and neo-colonialism. It must explain the necessity for, and the meaning and purpose of, a Union Government of Africa.

Our press must be foremost in inspiring and educating the masses of our continent so that they can withstand the onslaught of decadent ideas and influences that permeate the ranks of the opportunist and neo-colonialist agents among us. lf we are to banish colonialism completely from our continent, every African must be made aware of his part in the struggle. This is the kind of education which the African press can and must help to spread.

You have a noble cause — I would say a holy cause: to work unstintingly, unhesitatingly, and fearlessly for the equality of all our people in this continent for the universality of man’s rights everywhere on this globe. Yours is the responsibility to be ever on the alert for truth and to use it without fear or favour in the noble task of forwarding total independence in Africa.

You, by your calling, have the responsibility to work unceasingly for the unity of Africa, the single means by which we can promote the prosperity of this continent and defend it against the machinations of our enemies. By reason of your chosen work, you men and women of the press are in that most vital of positions where you can persuade men’s minds, inform their opinions and point the way to go. Unless you use it for good, you betray your calling, you mislead those who look to you for truth, who expect from you an interpretation of that truth in their cause.

The conclusions that you reach at this conference must sustain this position. They should assist in the speedy realisation of a union government of Africa. They should keep you in that place which no journalist should ever vacate — the vanguard of the march to freedom.

I therefore charge you to lead the final triumphant march of continent towards our unity which no imperialist or neo-colonialists will ever again be able to assail.

I wish you every success.

No comments:

Post a Comment