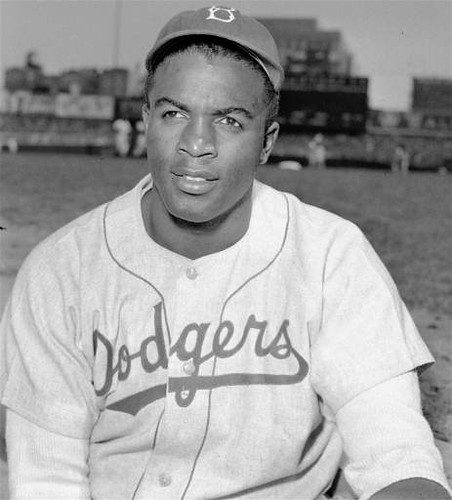

Jackie Robinson was the first African-American to enter Major League Baseball 62 years ago on April 15, 1947 with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Over the last few years the black presence in Baseball has declined tremendously., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

Friday, February 7, 2014 at 6:21 AM

‘Pitch Black’ traces African-American baseball history

Northwest African American Museum kicks off Black History Month with “Pitch Black,” a history of African-American baseball in Washington state.

By Nancy Worssam

Special to The Seattle Times

EXHIBITION REVIEW

‘Pitch Black: African American Baseball in Washington’

11 a.m.-5 p.m. Wednesdays, Fridays-Sundays, until 7 p.m. Thursdays, through Nov. 9, Northwest African American Museum, 2300 S. Massachusetts St., Seattle; $5-$7 (206-518-6000 or naamnw.org).

The story told in “Pitch Black: African American Baseball in Washington,” now at the Northwest African American Museum, is one that has been largely unknown. Players of color were long banned from the pro and minor leagues, and amateur play was seldom in the spotlight.

“Pitch Black” starts in the late 19th century in Roslyn, Kittitas County, where black miners played ball on their one day off. Take a look at the clunky, metal-soled miners boots worn on the playing field. This heavy footwear gave the players needed traction. They wore their miners caps — without the lamps — to keep the sun out of their eyes. Obviously, their will to play far surpassed the limitations of their equipment.

The exhibit is rich with memorabilia of this sort. There are uniforms, photo montages, trophies and baseball cards. Videos, newspaper clippings and informative wall panels enrich the story.

By the 20th century, baseball was the No. 1 national sport. Locally, black businesses sponsored teams. They didn’t pay the players, but put their business names on the team jerseys for the publicity. They also raised equipment money for the black teams playing at Garfield Park.

Soon black teams toured the country, initially playing for money against any team willing to take them on. In 1920 the Negro National League was formed, and other leagues followed. The first Negro World Series took place in 1927. In some ways these players were ambassadors paving the way for the civil-rights movement. They drew audiences wowed by their skill.

Here in Seattle, Sicks’ Stadium, funded by Emil Sick, the owner of the Rainier Brewery and a Pacific Coast League team, was home to the Seattle Steelheads of the short-lived West Coast Baseball Association Negro League.

Black youngsters practiced in every available open field, hoping to get good enough to play on one of the semiprofessional Negro teams. They were ready to endure the hardships of travel in a segregated country to have the thrill and status it conferred.

Baseball became a statement of citizenship and worth in Seattle’s black community. Women wanted to play, too — the exhibit includes pictures of the Seattle Owls Club of the 1930s, a women’s softball team that won the state championship in 1938 and the Seattle Championship in 1939.

When Jackie Robinson became the first black pro baseball player in 1947, Negro League activities began to wane, and by 1970 the Negro League was gone; black players were by then joining professional teams. Interestingly, although overall diversity on professional teams has increased, today, the percentage of American-born black players is the lowest since 1958.

The hands-on fun of this exhibit is a “dugout” where fans can play out their fantasies of baseball fame. Sit on the bench, handle the balls and bats, and try on the catchers’ chest padding and mask. Then step onto the pitcher’s mound, wind up and dream of glory.

Meanwhile, remember all the players and fans that preceded us.

Nancy Worssam: ngworssam@gmail.com

No comments:

Post a Comment