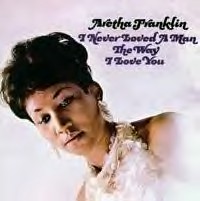

Aretha Franklin on the cover of her first recording with Atlantic Records in 1967. The release of this classic album made Aretha Franklin a household name and revolutionized rhythm & blues music.

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire Photo File

BY KELLEY L. CARTER

FREE PRESS MUSIC WRITER

Forty years ago on June 3, the saucy track from Aretha Franklin captured the No. 1 spot on Billboard's Pop Singles chart, and in the four decades since its release, folks have been singing it -- at times off-key -- ever since.

"Respect," as Franklin sang it, has been featured on the soundtrack of more than a dozen films, has been heard in numerous TV shows and has been belted out on many a karaoke night. The Grammy award-winning song has passed down through generations, crossed cultural divides and volleyed through musical genres.

The Queen of Soul's rendition of "Respect" is one of the most influential recordings in pop music history and one of the most indelible songs to come out of the rock and roll era. The single and the album it was featured on catapulted Franklin, who was 25 years old at the time, to global fame.

Timing played an integral role. The song added to a 1960s soundtrack of music, a grouping of songs that served as a backdrop to the pain and glory of a tumultuous time.

It gave an anthem to the civil rights movement and ultimately, it served as a call to arms for women everywhere.

"When Aretha Franklin released 'Respect,' it was a time where there was a lot of segregation in the music industry. Even though that segregation existed, she was able to rise above that segregation. 'Respect' touched every life that was breathing and had a pulse rate," said Dr. Lyn Lewis, a sociology professor at the University of Detroit-Mercy.

"It didn't matter whether you were male, female, black or white. Everybody can relate to 'Give me some respect.'"

How it came to be

It wasn't until 1967 that Franklin's career really took off. That was the year she recorded and released "I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You," the album that featured "Respect." The album is regarded as a soul music masterpiece.

Franklin worked with Jerry Wexler, an Atlantic Records producer who also is credited with coining the term "rhythm and blues." She went into the studios at Atlantic Records in New York on Valentine's Day of '67 to record the song, despite having a cold. The title track had already been released and had soared to No. 8 on Billboard's Pop Singles chart. Fans wanted more.

And Franklin gave it to them.

Before that day's session was over, Franklin recorded four singles for the album, including "Respect." She was more than familiar with the song before that day. She'd been performing it for nearly a year during her live shows, giving the song her own funk and making it almost unrecognizable from the original version, written and recorded two years earlier by Otis Redding.

"My sisters and I decided to add the sock-it-to-me's," Franklin said earlier this year, almost downplaying her role in the recording of the song. (She declined an in-depth interview for this story.)

Wexler said it was Franklin who brought the song to him, wanting to record it. He said she ultimately produced the track -- like she did on about 60% of the material they worked on together -- with her sister Carolyn Franklin doing the vocal arrangements.

Wexler was amazed at Aretha's handiwork. She'd done most of the arranging of the song long before she got to the studio, funking up the chords and figuring out how the rhythm would be laid down.

Perhaps the standout of the song was the way Franklin spelled it out -- R-E-S-P-E-C-T -- asserting her position with great vocal power. Franklin also added to the track a slang term popular in the black community at the time, "TCB," short for "take care of business."

Wexler said he added the musical bridge -- the only thing he thought Franklin's cover lacked.

Wexler said while he was in the studio laying down the track, Redding came by and instantly knew the song would do far greater things than his version.

"Little gal stole my record," the 90-year-old Wexler recalled Redding saying ruefully.

Layers of meaning

On its surface, "Respect" dealt with male-female relationships, with Franklin giving Redding's original piece of work a feminist twist -- it was demanding and had sexually aggressive undertones. But the song meant more than that.

Many treated it as a call to arms, a chance to right wrongs and level the playing field.

"We always sang songs about things we didn't have. We said, 'We shall overcome.' We hadn't overcome, but we sang 'We shall overcome,' " said Ben Chavis, a civil rights activist who worked with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as a youth coordinator and is the former chief executive officer and executive director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

"And when Aretha came out with 'Respect,' we weren't getting any respect. Black folks were being disrespected, being beat down, killed trying to get the right to vote. Being beat down and killed trying to get ... civil rights. And so when she came out with this song, 'Respect,' it was like she was fulfilling not only an urgency of the movement of that time, but she made known through her song that we were going to get respect."

Instantly, her song connected with everyday people who were fed up with those racial disparities.

"At this time, African Americans -- and African-American women in particular -- were looking for something that could serve as their anthem for that kind of era. And Aretha sang 'Respect' in a way that really caused black people to want to wave their liberation flag and wave their freedom flag. It was just a song that penetrated all aspects of the lives of black women," Lewis said.

The music was timely. In Detroit, blacks were dealing with issues of unfair housing practices and bum-steered urban renewal projects. The Police Department was predominantly white; only 8% of the force was black, which made for a substantial us versus them atmosphere.

"In Detroit ... things were starting to really kind of move, and people were starting to ask questions. So by the time you get to April of '67, there was a heightened sense of awareness.

"Martin Luther King had just given his speech about the Vietnam War ... in New York. Once that happened, that kind of took it to the next level. It really heats up at that point -- and then, around the same time, this single is released by a great singer who has great Detroit roots in Aretha Franklin, and she's not just singing about respect, she's spelling it," said M.L. Liebler, a professor at Wayne State University.

"And it's a strong declaration of independence. It fit perfectly with the momentum of the movement.

"And then in July of '67, we have the rebellion in Detroit. Many people also thought 'Dancing in the Streets' or 'Heat Wave' was a call to action. And those are all great songs -- Martha Reeves is wonderful if you ask me -- but 'Respect' had a different tenor to it that really kind of made you pay attention, and it still does."

Duke Fakir, an original member of the Four Tops and a friend of Franklin, said that this is how much of the music of the 1960s was. It was on a parallel track with the civil rights movement.

"They were doing the same thing. They were opening doors gently, wonderfully, with love with good soulful feeling. They were making people look at us in a different way and better ways, and 'Respect' was certainly one of those kinds of songs."

In the beginning ...

"Respect" demonstrated what Franklin could do vocally. She'd spent years recording for Columbia Records, and the work she did there was impressive, but not a true test of what she could accomplish.

Franklin, who was born in Tennessee but reared in Detroit, got her voice naturally. Her father, the Rev. C.L. Franklin, was a force in the civil rights movement, working with King and other icons. He was also one of the first ministers to record his sermons.

Aretha Franklin got the formula down early. She took a cue from the impassioned vocal deliveries that her dad gave at New Bethel Baptist Church in Detroit. There, he transmitted a mixture of singing and preaching, taking gospel music back to its roots: a transformation of something painful into something that people could believe in.

Her sermons were delivered through song, with a voice that sounds painful and beautiful all at the same time. "Respect" charted as a No. 1 hit during a year that was almost exclusively dominated by white men.

By the 1950s, the Rev. Franklin was taking his daughter on trips to record his sermons. On one of those recordings, he recalled being blown away sitting in his living room when he first heard Aretha's voice at 6 or 7, calling her a "stone singer."

Aretha Franklin's voice had a home in gospel music, and it was one that reinforced faith at difficult time in U.S. history.

Making the connection

Wexler, a former music critic who is credited with being one of the most influential players on the 1960s soul music scene, was determined to extend Franklin's voice to a larger audience. Wexler helped to build up Atlantic Records, which put out music by top acts including Ray Charles.

"She was my personal project," said Wexler. "I had heard her voice on her records on Columbia and it really demonstrated her brilliance, but they were not commercially feasible in my opinion and in the opinion of the buying public, because at Columbia, they tried to make her everything from Edith Piaf to Judy Garland to Peggy Lee.

"They tried this, they tried that. Nothing happened. But she made some beautiful records there. But they didn't have the handle. When I signed her up, I simply utilized the format that we had learned and developed with other female singers like Ruth Brown and Laverne Baker."

It was a formula that worked.

He encouraged Franklin to deliver songs using her powerful, rafter-rumbling gospel-tinged voice.

And when she delivered "Respect," her voice carried far beyond the African American community.

"Music and lyrics offer people a way to find its way into their head, by entering though their heart and their soul, which is a different kind of approach than some other things might be. It's more than just an intellectual exercise," said Liebler.

"Aretha Franklin isn't just an African-American singer for African-American women. That song is for everybody. Otis Redding was that type of an individual, too.

"Aretha's not just singing to a certain group. She's an artist. She's performing for everybody."

Contact KELLEY L. CARTER at 313-222-8854 or carter@freepress.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment