WORKERS WORLD IN 1971

The prisoners of Attica: Unity & courage vs. Rockefeller's machine guns

Published May 22, 2008 10:09 PM

Editor’s note: Workers World is in its 50th year of publication. Throughout the year, we will share with our readers some of the paper’s content over the past half century. Below is a reprint from a 1971 article on the massacre ending the most significant of many prison rebellions in a period in U.S. history when many Black, Latin@ and Native prisoners were conscious of their role in their peoples’ struggles for national liberation, when some were imprisoned political leaders of groups like the Black Panthers, and where even some white prisoners were political activists jailed for direct action against war and racism. On Aug. 21, 1971, Panther George Jackson was executed by guards in San Quentin state Prison, Calif. On Sept. 9, the Attica rebellion began. Prisoner Solidarity Committee leader Tom Soto, a contributor to Workers World newspaper, was among those few invited by the prisoners to witness the negotiations but who were unable stop the state’s vicious attack. For comparison, today’s population is incarcerated at over five times the 1971 rate.

ATTICA, N.Y., Sept. 14—Billionaire Governor Rockefeller yesterday ended with a massacre the greatest prisoners’ rebellion in modern times. Reflecting the blatant racism that has created the concentration camp system in this country and has led to prisoners’ revolts nationwide, a guard held hostage by rebelling inmates at Attica State Prison emerged from the prison’s main gate free and unharmed with a violent shout of “White power!” Behind him, within the prison walls, spewed a carnage of blood and bodies, including 28 dead prisoners and hundreds wounded, some fatally. Also dead were nine guards held as hostages, all, according to later autopsies, killed by bullets as 1,000 state troopers, sheriffs’ deputies and prison guards armed with shotguns, automatic weapons and nausea gas stormed the prison with guns blazing.

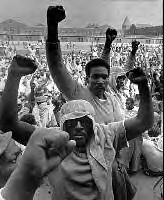

“It resembled the aftermath of a war,” some observers said, and they were right. Attica, with its prisoner population 85 percent Black and Puerto Rican and the high political consciousness and clenched fist salutes displayed during the rebellion, was one more battle in the continuing war for national liberation of the Black and Brown populations in the United States. Few believe that it will be the last.

On Thursday, September 9, over 1,000 prisoners, long abused by the all-white racist guard force, a vicious prison system, and an economic and political dictatorship held over the poor and working class of this country by the rich, rose up to overpower their tormentors. Within minutes, the inmates seized Cell Block D and 32 guards. Then, from a makeshift megaphone, the inmates issued their demands, many of which reflected the high political content of the rebellion.

Political demands raised

“An immediate end to the agitation of race relations by the prison administration of this State,” the prisoners demanded. An end to the racial discrimination against Brown and Black prisoners by the parole board; a replacement of the present parole board appointed by Rockefeller with a board elected by the people; the right to labor union membership while working in the prison and State and federal minimum wage instead of the present slave labor; constitutional right to legal representation at parole board hearings; “an end to the segregation of prisoners from the mainline population because of their political beliefs;” an end to guard brutality against prisoners; and later the prisoners added their demands for amnesty from criminal prosecution and “speedy and safe transportation out of confinement to any nonimperialist country.”

“Many prisoners believe their labor power is being exploited,” said the declaration of demands, “in order for the state to increase its economic power and to continue to expand its correctional industries (which are million-dollar complexes), yet do not develop working skills acceptable for employment in the outside society, and which do not pay the prisoner more than an average of forty cents a day. Most prisoners never make more than fifty cents a day. Prisoners who refuse to work for the outrageous scale, or who strike, are punished and segregated without the access to privileges shared by those who work; this is class legislation, class division, creates hostilities within the prison.”

The prisoners set up a People’s Central Committee which included Black, Puerto Rican and white members, organized their own typing pool and sound system. As for the hostages, according to Tom Soto of the Prisoners Solidarity Committee who saw them, the guards were being well treated, undoubtedly much better than the guards had ever treated the prisoners.

Rockefeller rejects amnesty

Nelson Rockefeller, billionaire governor of New York, disagreed. “To do so (grant amnesty) would undermine the very essence” of American society, he said. From the barbed-wire seclusion of his 3,000-acre private estate at Pocantico Hills, Rockefeller rejected the plea of the mediating committee for him to join the negotiations. Instead, this brother of the head of Chase Manhattan Bank ordered the full mobilization of the National Guard units in western New York to prepare a massacre of Attica’s inmates.

The demands of the prisoners were never seriously considered, and the most fundamental of the demands, amnesty, was never considered by the State. To the prisoners, this was crucial as many were in danger of being framed up on murder charges for the death of a sympathetic guard killed by other guards when the rebellion broke out.

Meanwhile, the troop buildup outside the prison continued. Sheriffs’ deputies poured in from 13 surrounding counties in their own automobiles, armed with shotguns and 30-30 hunting rifles for “the turkey shoot,” as one racist called it. It was clear that Rockefeller’s government was not negotiating in good faith.

Under cover of “negotiating,” they were preparing the massacre, as hundreds of National Guard troops were moved into the area on Sunday. Police outside the prison grew increasingly hostile to arriving crowds of prisoners’ supporters and relatives. One state trooper leveled his shotgun at members of a delegation of the Prisoners Solidarity Committee and growled, “Get out of the roadway or we’ll wipe you out!”

Meanwhile, relatives of prisoners were denied access to the prison grounds by police, although relatives of hostages were allowed in. A roadblock one mile from the prison sealed off the prisoners from their relatives and outside supporters. As far as the State was concerned, the prisoners’ families had no rights. A curfew was also imposed in the town of Attica to prevent angry Black, Brown and white supporters from exercising their right to be at the scene.

Rockefeller’s government had also decided the prisoners had no rights. Not even the right to live.

Yesterday, Monday morning, the State’s mobilization was completed, and by 8 a.m., 1,700 troops armed with machine guns, automatic rifles, tear and nausea gas, shotguns, and high pressure hoses were poised for the attack. At 9:45, Oswald gave the signal for the attack to begin. Two Army helicopters circled over the northeast corner of the 55-acre compound where the prisoners were gathered. One dropped canisters of nausea gas onto Cell Block D, while the other swooped down on the men below, firing automatic weapons into the crowd of prisoners, shooting them down in “Vietnam” fashion. The prisoners had no weapons to return the fire but defended themselves as valiantly as they could. Their only means of defense was handmade weapons. It was a massacre.

Capitalist press lied!

Yesterday the capitalist press was full of horror stories of hostages with their throats cut, mutilations and executions. The racist hysteria against the prisoners’ uprising was being carefully fanned. Today the truth came out—the guards were all killed in the same murderous assault by police and national guards on the prisoners.

So far, twenty-eight prisoners and nine hostages were reported killed, hundreds of prisoners wounded. The 28 surviving hostages were taken for treatment to a nearby hospital, while the hundreds of wounded prisoners waited for treatment in a small room in the prison, 8 by 10 feet, the floor covered with blood. “It’s the worst thing I’ve ever seen,” said one doctor emerging from the prison gate in a bloodstained gown.

Asked if he had any second thoughts after seeing the resulting massacre, Commissioner Oswald patted his huge stomach and calmly replied, “No, I don’t.” Nelson Rockefeller had no second thoughts either. He agreed that the security of the whole rotten prison system was at stake. The highly political content of the prisoner demands was also a direct challenge to the dictatorship of wealth enjoyed by millionaires like Rockefeller. This was not just a prison rebellion but part of a larger class war going on across the country. This was recognized on a national level as President Nixon personally phoned his congratulations to the Governor. Rockefeller was, of course, delighted.

The people were not. Prisons around the country stirred with anger. In Baltimore City Jail, the second revolt within a year broke out, and prisoners of Cleveland County Prison also rebelled. Throughout New York, Rockefeller ordered all inmates in the state’s maximum security prisons confined to their cells in fear of spreading rebellion. Rockefeller, sipping his mint julep at his Pocantico Hills estate, may have been delighted with Nixon’s support, but he was frantically worried about the rising tide of people’s vengeance that is increasingly threatening to sweep him and his wealthy class into the dustbin of history.

Once in a very great while a rich man goes to prison. Maybe he’s taking a six-month rap for a company that defrauded the people out of millions; when he gets out after his brief stretch, he’s set for life. And even while he’s in, every little comfort is provided for him, so that the time passes as pleasantly as possible.

Most of all, he is never really isolated, never forgotten. His lawyers visit him constantly, the guards treat him like a “gentleman,” and he is able to conduct his business affairs from prison.

Prisons weren’t made for people like this. The fact that a handful of them may be in a few federal institutions is largely an accident.

But the prisons are full, overflowing, exploding with poor, oppressed men and women for whom prisons have meant the end—of life, of happiness, of friends and family. The first stretch becomes a stigma that dooms a young person to a life behind bars. The prisoner never sees a lawyer, is prevented from defending himself, is estranged from his or her family just out of the sheer impossibility of visits to isolated prisons, and can look forward to desperation and disappointment when and if he ever hits the streets again.

For thousands of prisoners, especially the large percentage of Black and other oppressed people routed into the prisons from birth, these conditions have become unbearable. The terrible isolation imposed by the racist authorities has been broken again and again in the only way left to human beings who have been literally sealed in their own tombs: by open rebellion. These rebellions are specifically directed at the numberless injustices that read like a description of the Chamber of Horror; but they are also something more.

They are a passionate cry to brothers and sisters on the outside, a desperate affirmation that they are alive, there on the inside; they are human beings who, while treated worse than animals, have not been crushed, whose spirit lives on in rebellion.

The Prisoners Solidarity Committee is another absolutely indispensable product of this new spirit. It was formed less than a year ago, when prisoners at Auburn, N.Y., wrote to organizations on the outside for help. Youth Against War & Fascism responded, and soon helped form the Prisoners Solidarity Committee. The committee has expanded to many cities since then, and includes relatives of prisoners and released prisoners themselves.

When news of the PSC reached the jails, it released a dammed-up flood of letters from brothers and sisters telling of the indignities, the brutality, the pain that is a daily part of prison life. But these letters all told something else. They were not pathetic appeals from beaten people; they rang with hope and strength and willingness to struggle. Moreover, the writers were thrilled that they were finally breaking out of their isolation, that people outside were listening and working with them.

The PSC published some of these letters in the pamphlet,

“Prisoners Call Out: Freedom!”

The PSC raised some money with this pamphlet and social affairs, and rented a bus so that prisoners’ relatives could get to Auburn and visit them. For many of them, it was the first visit in years.

When the Auburn 6 had several court hearings, the PSC got sizable demonstrations of support, even in blizzard conditions. More and more, the PSC became a vehicle whereby the prisoners themselves could speak to the people outside, could generalize their struggle, fuse their grievances and their hopes into the main current of rebellion that is rising in the country as a whole.

The PSC, on hearing of the rebellion, had immediately mobilized all its strength: it sent a delegation to Attica, arranged transportation for relatives, and organized many demonstrations throughout New York State and in several major cities elsewhere. The prisoners knew about all this, and knew that what they had to say would be heard on the outside.

At the most difficult moments, when ruling class hysteria against the prisoners reached its height, the PSC announced from inside Attica that it unconditionally supported the prisoners’ demands. A further bond of love and trust was forged in those tense hours.

The isolation of the prisons has been permanently shattered. Even the highest concrete wall, the darkest cell, the cruelest solitary “hole” can no longer hold the terror it once had, for 1,500 men at Attica have looked the worst in the face.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Articles copyright 1995-2008 Workers World. Verbatim copying and distribution of this entire article is permitted in any medium without royalty provided this notice is preserved.

Workers World, 55 W. 17 St., NY, NY 10011

Email: ww@workers.org

Page printed from:

http://www.workers.org/2008/us/ww_1971_0529/

No comments:

Post a Comment