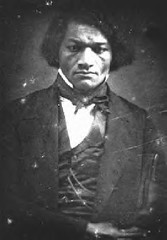

Frederick Douglass, anti-slavery organizer and journalist. His July 5, 1852 speech in Rochester, New York is still cited some 155 years later.

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire File Photos

Op-Ed Contributor

Two Can Make History

By DEBBY APPLEGATE

New York Times

New Haven

OVER the last few months, the contest between Senators Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama for the Democratic presidential nomination has been compared to the bitter feud between Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Frederick Douglass, two of the most famous progressive reformers of the 19th century.

They had been colleagues and friends through two decades of public service — Douglass, the former slave who gained international fame as a writer, editor and activist, and Stanton, who began her career by organizing the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls in 1848. They had worked closely together on a variety of social reform issues, particularly abolition.

But in 1869, Douglass and Stanton were torn apart by the 15th Amendment of the Constitution, which stipulated that the right to vote cannot be denied on the basis of race, color or previous condition of servitude. Gender remained a perfectly legal reason to keep someone off the voter rolls.

During the Civil War, many women, including Stanton, had willingly put aside the fight for women’s rights to campaign for the emancipation of the slaves. After the war, they had even stood by patiently when, in 1866, Congress passed the 14th Amendment, defining citizens specifically and solely as “male” — the first use of the word “male” in the Constitution. The politicians soothed the women’s rights advocates by assuring them their turn would come soon.

But in 1869, when outraged women demanded to know why they were not included in the right to vote, they were informed by their allies in Congress that public opinion left room for just one minority group to make it through the door of suffrage and that this was “the Negro’s hour.”

Stanton felt shocked and betrayed that, once again, women were being left behind while black men advanced. When Douglass reluctantly supported the 15th Amendment as written, Stanton responded with a series of furious attacks, ridiculing the idea of giving the vote to the “lower orders” of men, including blacks, Irish, Germans and Chinese, while native white women were denied it. Her campaign to reject the amendment created a bitter schism in the long alliance of abolitionists and suffragists, and within the suffrage movement.

Now that Senator Obama has nearly clinched the nomination, this historical analogy is being used to support a variety of points: that in the “oppression sweepstakes” women always “lose” to blacks, that when thwarted in their ambitions, white women will resort to angry racism, that liberal coalitions are mere screens for self-interested identity politics that fracture whenever real power is at stake. But the analogy is flawed and so are the lessons we’ve been drawing from it.

The most obvious difference between the quarrels of 1869 and 2008 is that a presidential candidate is not the same thing as a huge swath of the American population. There’s only one president, but there was no intrinsic reason both blacks and women couldn’t attain the rights of citizenship or suffrage at the same time.

Of course, it wasn’t black men or white women who decided that there wasn’t room for them both to enter. After all, neither group could vote in the ratification process. Stanton and Douglass may have had a lot to say to each other and the press, but neither of them had any say in the wording of the amendment.

Instead, this was decided by a coalition of Republican politicians in Washington who supported black suffrage — and thus the creation of a sure new population of black Republican voters — as a way to shore up their precarious majority in Congress. (There were nobler motives as well, but the timing of the amendment was all politics.)

The exclusion of women was also a partisan decision, since enfranchising white women would run the risk of creating as many new Democratic voters as Republicans. The Republicans’ public line, however, was that the amendment would have no chance of ratification if it were so bold as to offer universal suffrage.

Not everyone bought this argument. As the famous Republican preacher and reformer Henry Ward Beecher said to the women of the American Equal Rights Association in 1867: “If you have any radical principle to urge, any higher wisdom to make known, don’t wait until quiet times come, until the public mind shuts up altogether. We are in the favored hour; and if you have great principles to make known, this is the time to advocate them.”

Beecher turned out to be right. The 15th Amendment marked the end of the public’s commitment to major social change. Within the decade, the Republican Party had shed its progressive activism to become the party of big business and laissez-faire policy. For women, five decades would pass before the 19th Amendment gave them the vote in 1920. For blacks, the spread of Jim Crow laws would prevent many from exercising their Constitutional rights until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, almost a century later.

But history is not destiny. The Douglass-Stanton brouhaha need not be precedent, need not incite Mrs. Clinton’s female supporters to turn against Mr. Obama in anger or, as a vocal minority has already threatened, to cast protest votes for Senator John McCain.

Perhaps it is even possible to correct the mistakes of 1869: Senator Obama may have claimed the “historic first” entry point to the White House, but couldn’t Senator Clinton receive the vice presidential nomination, allowing both black and white, male and female, to enter that door together? After all, we’ll all have a say this time around.

Of course, we again are hearing the old discouraging response: No, Mrs. Clinton cannot share the ticket because history shows that “the public mind” is too conservative to accept both a black man and a white woman in the seat of power.

But if history offers a lesson here, it is not that Americans cannot handle too much change at one time or that we must inch our way, one by one, through the door of equality. Rather, it is that opportunities for genuine change are rare and when they occur we must kick the door off the hinges while we can. It is much harder to pry open the public mind once it has shut itself up again.

Debby Applegate is the author of “The Most Famous Man in America: The Biography of Henry Ward Beecher.”

1 comment:

Good Day!!! panafricannews.blogspot.com is one of the best resourceful websites of its kind. I take advantage of reading it every day. I will be back.

Post a Comment