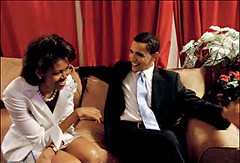

Michelle Obama with Senator Barack Obama enjoying a laugh. The Illinois Senator sealed the nomination for the Democratic Party on June 3, 2008.

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire File Photos

By Dan Balz and Anne E. Kornblut

Washington Post Staff Writers

Wednesday, June 4, 2008; A01

With a split decision in the final two primaries and a flurry of superdelegate endorsements, Sen. Barack Obama sealed the Democratic presidential nomination last night after a grueling and history-making campaign against Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton that will make him the first African American to head a major-party ticket.

Before a chanting and cheering audience in St. Paul, Minn., the first-term senator from Illinois savored what once seemed an unlikely outcome to the Democratic race with a nod to the marathon that was ending and to what will be another hard-fought battle, against Sen. John McCain, the presumptive Republican nominee.

"Tonight we mark the end of one historic journey with the beginning of another -- a journey that will bring a new and better day to America," he said, as the emotion of the moment showed on his face. "Because of you, tonight I can stand before you and say that I will be the Democratic nominee for president of the United States of America."

Obama's success marked a major milestone for the nation -- a sign of the racial progress that has taken place during the span of the senator's lifetime. But the nomination battle also revealed a racial schism within the Democratic Party, and potential resistance to a black candidate in some parts of the country that will play out in the general-election campaign.

Obama's victory was notable not simply for its historic importance but also because it marked a rejection, albeit by the narrowest of margins, of a candidate who represented the most powerful family in Democratic politics. Clinton's defeat seemed almost inconceivable a year ago as the race was beginning to unfold, but Obama and his advisers proved equal to the challenge.

In the last two primaries, Obama won Montana but lost to Clinton in South Dakota, a continuation of the seesaw battle the two waged from the first caucuses in Iowa in January through more than 50 other contests. They fought the most closely contested Democratic nomination battle in the modern era and split the party into two almost equal coalitions.

But with the help of superdelegates who declared their allegiance to Obama throughout the day, he easily crossed the threshold of 2,118 delegates needed to secure the nomination around the time polls had closed in Montana and South Dakota, closing off the last slender hope Clinton had to take away the nomination.

During his speech, Obama offered praise to his rival. "She has made history not just because she's a woman who has done what no woman has done before, but because she is a leader who inspires millions of Americans with her strength, her courage and her commitment to the causes that brought us here tonight," he said.

Obama still faces a sizable job of uniting his party, and his uneven performance during the final months of the nomination battle could make Clinton's supporters more difficult to win over quickly. Clinton has pledged to help unify the part, but last night she signaled that she will do so on her own timetable.

Clinton, who waged a fierce campaign to become the first woman nominated for the presidency, spoke shortly before Obama at a rally in New York. Amid questions about when or whether she would quit the race, she declared: "This has been a long campaign, and I will be making no decisions tonight."

Earlier in the day, she opened the door to considering to be Obama's vice presidential running mate, should he make the offer, leading to speculation about what her goals will be.

"You know, I understand that that a lot of people are asking, 'What does Hillary want? What does she want?' " she said. She then ticked off a list that included ending the war in Iraq, improving the economy and providing universal health care. But in a clear statement aimed at Obama, she added: "I want the nearly 18 million Americans who voted for me to be respected, to be heard and no longer to be invisible."

Obama spoke at the Xcel Energy Center in St. Paul, the arena where McCain will accept the Republican nomination in September, and he used much of his speech to cast McCain as a continuation of the Bush presidency. But before Obama took the stage in Minnesota, McCain was on television from New Orleans with a speech that challenged the Democrat in an outline of the debate that will take place between now and November.

"This is, indeed, a change election," McCain said. "No matter who wins this election, the direction of this country is going to change dramatically. But the choice is between the right change and the wrong change, between going forward and going backward."

The last day of the primary-caucus season provided a fitting conclusion to the long nomination battle, a day of extraordinary drama, frenzied speculation and fast-changing events. Obama's campaign worked furiously to pressure uncommitted superdelegates to endorse him, Clinton's campaign struggled to provide her with time to leave the race on her own terms, and the media breathlessly sought to keep pace.

Yesterday began with an unexpected report by the Associated Press that said Clinton would use her rally last night to concede. Campaign chairman Terence R. McAuliffe immediately went on CNN to deny the report, and a short time later the campaign issued a terse statement: "The AP story is incorrect. Sen. Clinton will not concede the nomination this evening."

But inside the campaign there was confusion as aides struggled to figure out what had triggered the report, and expressed uncertainty about the day ahead. "This is very much a work in progress," a senior Clinton adviser said.

Clinton fought a rear-guard action, with her campaign officials pleading with superdelegates and party leaders to give her the dignity of a graceful exit and an election-night rally in which she could celebrate her long campaign rather than concede to her rival.

Senate Majority Leader Harry M. Reid had exhorted a group of uncommitted senators on Monday to hold off their declarations until today, and he repeated that plea publicly yesterday. "Senator Clinton needs to be left alone. . . . Let this week work its course," he told reporters at the Capitol.

The only remaining question was when -- not whether -- Clinton would step aside. Some advisers, including former chief strategist Mark Penn, reportedly urged her to consider the full range of options, other than quitting outright. Others counseled her to consider her options -- and her legacy.

Aides said the end is likely to come by week's end but could be signaled as soon as today.

Talk of a possible Clinton vice presidency came out of a discussion she held with supporters in the New York congressional delegation. Rep. Nydia M. Velazquez (D-N.Y.), told The Washington Post that she had implored Clinton to think about the passionate support her candidacy has received from Latino voters, who will be crucial to Democratic chances in November.

"She said if she was asked, she would consider it," Velazquez said. "She said, 'Look, I will do whatever it takes to defeat McCain in November.' "

Elected to the U.S. Senate in 2004 after eight years in the Illinois Senate, the 46-year-old Obama, the son of a black Kenyan father and a white mother from Kansas, accomplished something that few thought possible when he began his candidacy in February 2007 against the heavily favored Clinton.

Clinton, the former first lady and a second-term senator from New York, seemingly held all the advantages, including a vast network of fundraisers, a web of political supporters in virtually every state, and the allure of being able to restore to power a family that had given the Democrats control of the White House for eight years under her husband.

Obama proved to be an even more prodigious fundraiser, tapping the Internet as no candidate ever had to raise millions more than his rival, and also grabbed hold of a powerful movement of grass-roots supporters and volunteers who helped fuel his candidacy and provided a built-in base of organization across the country.

He also tapped effectively into a hunger for change after eight years of the Bush administration. In a Democratic campaign that, initially at least, was cast as experience vs. change, Obama proved to have found the more powerful message.

Obama's victory -- and Clinton's unexpected third-place finish -- in the Iowa caucuses in January upended expectations for the nomination battle and set the candidates on an epic struggle that continued until the polls closed last night.

With an 11-contest winning streak in mid-February, Obama built what turned out to be an insurmountable lead in pledged delegates, then held on in the campaign's last three months as Clinton ticked off victories in states such as Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Kentucky and Indiana.

Meanwhile, Obama effectively turned the tables on Clinton among the party leaders and elected officials who make up the nearly 800 superdelegates. After Clinton built a substantial lead among that group in the early stages of the race, Obama steadily gained ground and then surged ahead with these party insiders. Once that began, Clinton's hopes of winning the nomination effectively came to an end.

Kornblut reported from New York. Staff writers Shailagh Murray, Paul Kane and Jonathan Weisman contributed to this report.

Two Words With a Ring Of Possibility

By DeNeen L. Brown

Washington Post Staff Writer

Wednesday, June 4, 2008; C01

Black president.

Two words profound and yet contradictory. Once thought of as an oxymoron, impossible to be placed together in the same sentence, context, country -- unless followed by a question mark.

Black president? This century?

Black president -- words perhaps as foreign as "green president." And yet now, a black president seems a distinct possibility with Sen. Barack Obama heading into the general election as the Democratic presidential nominee.

Black president. The two words evoke excitement, dread, great expectations, intense fear, incomprehension, power, the breadth of possibility.

For some, those two words -- black president -- symbolize the smashing of a glass ceiling, whose splintered shards had fallen on others who had thrown rocks at it in vain.

Black president, words that carry with them the hope of the Invisible Man, the Manchild in the Promised Land, the balm on the anxiety of a Native Son.

Said with whispers. And gasps. Exhaled as if the accumulation of all the troubles of a people would be over, though those who know better know also that that won't happen.

"Black president. Is there still racism in this society? Of course there is. But it is not nearly the level of racism that would make the idea of the words 'black president' sound ridiculous," says Roger Wilkins, professor emeritus at George Mason University. "Black president. . . . It is not as if one morning I woke up and turned on the radio and I heard someone say 'black president,' I would drop my teeth. This has been gradual. When I hear it, I think as someone who has taught history for the last 25 years; I think our country has come a long way."

Wilkins adds: "There is a very deep joy and pride when I listen to the words 'black' and 'president' applied to a walking, breathing person who carries African genes in his body and soul."

And yet, for others, there is symbolism of a different kind. A symbolism of fear. Geraldine Ferraro, the first female vice presidential candidate, has said Obama is a candidate for president only because he's black. And she's raised the specter, in her recent writings, of a "reverse racism" that some whites fear under a black president.

"They're upset because they don't expect to be treated fairly because they're white," Ferraro wrote Sunday in the Boston Globe, adding, "They don't believe he understands them and their problems."

A black president is old hat in the movies. Television shows also have portrayed black men in the Oval Office. Comedians joke about black presidents. There is even a rock band called Black President, which has posted online: "when we came up with the name of the band, senator obama had not yet announced his intentions to run for office. it was just our way of saying america needed a change and we could think of nothing more indicative of change in a racist, soulless system than a BLACK PRESIDENT." (But the band has not endorsed a candidate, according to its Web site.)

Because of his appeal to whites, some call him "post-racial," this man, Obama, who didn't run as a black president, whose mother is white. Yet people still call him the first black presidential nominee. "Post-racial" meets the "one-drop rule" from the days of Jim Crow?

Race gets elastic that way -- stretched well beyond the truth some years ago when Toni Morrison called Bill Clinton the country's first black president. It insulted some black men, being compared to Clinton and his misdeeds. But the words stuck. Pretty or not.

In January, during a debate, someone asked the question of Obama: "Do you think Bill Clinton was our first black president?"

"Well," said Obama, pausing as the audience chuckled, "I think Bill Clinton did have an enormous affinity with the African American community and still does. That's well earned."

But months later, after lots of black folk felt the former white president was race-baiting, his "black president" title was revoked.

Now, the title is poised to be passed on, to Obama.

Everybody knows there are no guarantees in politics. But this "black president" idea is electrifying fodder for thought.

There is Artis Allen, 74, a retired meat cutter, leaning against a rail at a post office in Silver Spring, pondering those words -- black president -- and reflecting on his childhood.

"Black president? No, not then. When I grew up in Georgia, it was very prejudiced. I remember a man who ran for governor. He said he did not want a black vote. Black people couldn't vote too much anyhow. I was 13 and my daddy wasn't a politician, but that was his main conversation: politics."

"Black president," Allen repeats. "What surprises me is white people are voting for a black man just as much as black people. That is what really amazes me."

Down the street, the words "black president" stop Ali Salaam, 32, a barber who, like Allen, is black.

"Black president, what does it symbolize?" Ali says. "Elite status, the best of the American dream. That's what it evokes for me. I love it. I always believed it could happen. I didn't think I would see it happen in my lifetime. But once I heard him speak, I believed it. When I heard him speak, it reminded me of King, Du Bois, Malcolm X. It was entrancing."

Steven Warren, 16, a junior at Archbishop Carroll High School, says the words are "revolutionary. I didn't think it would happen while I was in my prime. I thought it would happen when I was in my 60s."

"You can take the black out and he still would be president," says the young black man.

Up the street you go, carrying the words, black president. The words stop at the feet of Tommy Thayer, 30, a tattoo artist. "It's a damn shame there hasn't already been a black president as far as I'm concerned," Thayer says. "We are so used to all the presidents being all whites and all men. That's like telling everyone we are a racist nation. I think people are robbing themselves if they don't get to know other cultures."

Thayer describes himself as "all white, 100 percent white, Irish, Italian if you want specifics. . . . He's going to win. I'm almost positive. I can feel it. We are going to have a black president."

Well, for now, a black presidential nominee.

No comments:

Post a Comment