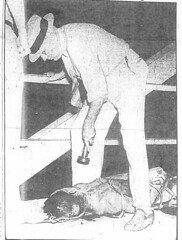

Tipton County, Tennessee Sheriff W.J. Vaughn Flashes Light on Lynching Victim Albert Gooden During Early Morning Hours of August 17, 1937

Originally uploaded by panafnewswire

Slavery by Another Name: Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II

A Note on the Interview

We are publishing this interview courtesy of “Beneath the Surface” radio show hosted by Michael Slate on KPFK, Los Angeles. The views expressed by the author in this interview are, of course, his own, and he is not responsible for the views expressed elsewhere in this newspaper.

Douglas A. Blackmon’s new book, Slavery by Another Name – The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (Doubleday, 2008) has unearthed ugly chapters of U.S. history that have been buried for decades. In graphic and truthful detail, Blackmon’s powerful book reveals the widespread use of bonded labor after the Civil War—and how this amounted to a new form of slavery that incorporated many of the same inhuman conditions of brutal confinement like shackles, whippings, hog-tying. and water torture.

Douglas A. Blackmon, the Atlanta Bureau chief of the Wall Street Journal, has written about race and especially the interplay of wealth, corporate conduct, and segregation. In 2000, the National Association of Black Journalists recognized Blackmon’s stories revealing the secret role of J.P. Morgan & Co. during the 1960s in funneling funds between a wealthy northern white supremacist and segregationists fighting the Civil Rights Movement in the South.

On May 6, Michael Slate interviewed Blackmon on “Beneath the Surface,” KPFK radio in Los Angeles, 90.7 fm (streaming worldwide on kpfk.org every Tuesday from 5 to 6 pm Pacific time). The following is the transcript of that interview.

*******************************************************************

Michael Slate: At the end of your book you say you feel that that period of time between the betrayal of reconstruction, the destruction of reconstruction, and World War 2 and maybe even beyond World War 2 and into the 1950s, you talk about how that should not be called the Jim Crow era, but rather that it should be called “the age of neo-slavery.” Can you explain that?

Douglas Blackmon: Sure. There are two points that I'm really making there. One is in some respects the biggest demonstration that I hope the book makes. And that is that this period of time, beginning at the end of the 19th century and continuing up into World War 2, as a country we have shared in a national instinct to have a sort of collective amnesia, or at a minimum, a minimization of the reality of the things that really happened to African Americans all across the South in that period of time. And one aspect of that minimizing the offenses of this period, has been to call it the Jim Crow era. Now I don't think that's what people intended when it began to be known as that, but in hindsight, that's fairly clear to me. Jim Crow was a character that was played, in the beginning, by a particular actor who would perform in blackface and do comedy routines that were meant to denigrate Black Americans. Before the Civil War that became an incredibly popular form of entertainment.

After the Civil War, Jim Crow came to define the entertainment of that era, and the symbolism of Blacks in the South. I liken that to our calling the 1930s in Germany, if we named that period of time after the most popular anti-Semitic comedian of Germany at that time. I think we would all recognize that that was an offensive way to refer to that period in history. The reality, what Slavery by Another Name demonstrates, I think, is that in truth, since the beginning of the 20th century, a new form of forced labor involving hundreds of thousands of people, and terrorizing hundreds of thousands of other people, had emerged in the South, that amounted to what I call “neo-slavery,” and we should call it what it was, the age of neo-slavery.

Slate: I have studied that period to a certain degree and had some sense of what happened after the Civil War, after the Confederacy was defeated. You depict a sense of freedom when you speak about it in your book, but when you're talking about the age of neo-slavery, you're talking about a whole new stage of slavery that came after Reconstruction, right?

Blackmon: Yes. After the Civil War, African Americans in huge numbers, all across the South, experienced an authentic period of emancipation. Now, it was never as it really should have been. It was a tough time, and a world of poverty and deprivation of services, and great difficulty and great animosity between Blacks and whites at that time. So it wasn't a perfect time, but it was an era in which millions and millions, and there were four million Blacks, essentially, at the end of the Civil War in the South, and huge numbers of those people participated in free elections. They were accorded the full rights of being citizens as guaranteed by the Fifteenth Amendment. They had jobs; they had farms; they had employment of various kinds. Like I said, it was a difficult, poverty-stricken time, but there was true emancipation and true freedom.

But what began to happen in the South, particularly after federal troops were removed in 1877, and even more so after another 15 years when it became clear that there was no possibility that white northerners would ever send federal troops back to enforce civil rights, all across the South, the state legislatures of every state passed laws which began to effectively criminalize Black life and to create a situation in which African American men found it almost impossible not to be in violation of some misdemeanor statute at almost all times. And the most broadly applied of those was that it was against the law if you were unable to prove at any given moment that you were employed. So vagrancy statutes were used to arrest thousands of Black men, even though thousands of white men could have been arrested on the same charges but they hardly ever were. And then, once arrested, the judicial system had been re-tooled in such a way as to coerce huge numbers of men into commercial enterprises as forced workers through the judicial system. And then thousands of other people lived in fear of having that happen to them, and that was part of how they were intimidated into going along with other kinds of coercive labor, like sharecropping and farm tenancy and many other things.

Slate: Give people a sense of the scope of this, because in your book you concentrate a lot on Alabama. I really liked the device you used. I really thought that was very powerful, that woven through it is this one character that you're searching for—where was he from and what happened to him and what was his life before that, his ancestors and what's happened since—but you unfold something. It concentrates a lot on Alabama, but the scope of this was huge, both in terms of the numbers of people involved, as well as the spread across the South.

Blackmon: This was a phenomenon that by the beginning of the 20th century, in effect, as of 1901, every southern state had completely disenfranchised virtually all African Americans. There was no Black voting of any meaningful degree still occurring in the South after 1901. And every southern state had some version of this array of laws that could be used to arrest almost any Black man who did not live under the explicit control and protection of a white man. And every southern state in one manner or another had adopted the practice of, rather than imprisoning the people who were convicted of these flimsy or fictitious crimes, actually leasing them out to commercial enterprises for periods of one or two years or sometimes much longer periods of time as forced workers. And Alabama was the place where the system lasted the longest in its most explicit form, and was the most evolved in terms of how every county government [was involved] and the enormity of the numbers of African American men who were leased by the state. And in the case of Alabama, there were at least 100,000 African American men between the 1890s and the 1930s, or about 1930, at least 100,000 African American men were leased or sold by the state of Alabama to coal mines, iron ore mines, sawmills, timber harvesting camps, cotton plantations, turpentine stills, all across the state.

There were at least another 100,000, and I suspect many more—the records are incomplete—but at least another 100,000, just in Alabama, who were similarly leased out of the local courts, just where a county judge, in cooperation with a local sheriff, would parcel out all of the prisoners that were rounded up and brought to the county jail. And so at least 200,000, it's probably more like 250,000 to 300,000 African Americans, just in Alabama, were forced into the system, just in the most informal ways. And there are very well documented records of thousands of Black men who died under these circumstances during that period of time. And I document in the book the stories of men like Jonathan Davis, who in the fall of 1901, left his cotton field to try to reach the home of his wife's parents, where she was being cared for and would soon die of an illness. He was trying to reach her before she died. And on his way to the town 15 or 20 miles away where she was being taken care of, he was accosted on the road by a constable, and essentially is kidnapped from the roadway and sold to a white farmer a few days later for $45. And that is something which happened, in the book I name dozens of people that happened to. It's clear some version of that sort of kidnapping happened to hundreds and hundreds of other African Americans. And again, all of that is just in Alabama, and there were versions of this going on in all of the southern states. So in reality, there's no doubt in my mind that hundreds of thousands of African Americans had these events occur to them, and millions of African Americans lived in a form of terror of this happening either to them or to their family members.

Slate: When you talk about re-enslavement, people might have the reaction, “Wait a minute, re-enslavement, was it really as bad as slavery?” Can you give people a sense of the conditions that you've actually documented? Because they were horrifying.

Blackmon: Well, Green Cottenham, the character you referred to a moment ago, who much of the book is woven around; the wife of Green Cottenham; the family of slaves and former slaves that he descended from. And what happened in the course of slavery's resurrection and how it began to intrude upon the lives of those former slaves and their descendants. And finally Green Cottenham, as he rises into the delta in the beginning of the 20th century, is arrested in Columbiana, Alabama, outside the train depot in a completely spurious situation where initially it's claimed that he broke one minor law, and then later it's claimed that he broke a different minor law, and so finally he was brought before the county judge three days later. The judge, to settle the confusion, simply declares him guilty of yet another offense, of vagrancy. On the basis of that, he's fined, $10 I think was the actual fine, and then on top of that he's charged a whole series of fees associated with his arrest: a fee to the sheriff, a fee to the deputy who actually arrested him, some of the costs of his being jailed for three days, fees for the witnesses who testified against him, even though as far as I could tell there were no witnesses. All of these things added up to effectively about a year's wages for an African American farm laborer at the time, and an amount that obviously somebody like Green Cottenham, an impoverished, largely illiterate African American man in 1908, could not have paid.

So in order to pay those fines off as part of the system, he is leased to U.S. Steel Corporation, a company that still exists today, and forced to go to work in a coal mine on the outskirts of Alabama, with about a thousand other Black forced laborers. And those men lived under almost unspeakable conditions. They worked much of the time deep in the mines in standing water, which was the seepage, which would come out from under the earth. They were forced to stay in that water and consume that water for lack of any other fresh water, even though it was putrid and polluted by their own waste. They had to operate in these unbelievably cramped circumstances. Any man who failed to extract at least eight tons of coal from the mine every day would be whipped at the end of the day, and if he repeatedly failed to get his quota of coal out, he would be whipped at the beginning of the day as well.

The men entered the mine before daylight. They exited the mine after sunset. They lived in an endless period of darkness under these horrifying circumstances. They had little medical care. They were subject to waves of dysentery and tuberculosis and other illnesses, and it was ultimately one of those epidemics of disease, which caused Green Cottenham to die five months after he arrived at the jail, in August of 1908.

And those conditions, and far worse ones even, were incredibly common in the forced labor camps that by then had emerged all across the Deep South.

Slate: One of the terrible ironies you bring up in your book is that in the previous form of slavery, a slave owner was a little more hesitant to actually outright kill a slave because there was a lot more invested in the slave. But in this neo-slavery, that was one of the ways they exercised their terroristic dominance over the mass of forced laborers. A slave's life was inconsequential.

Blackmon: That's right. Before the Civil War, in the antebellum slavery that we all know more about, or at least think we know more about, under that system, as terrible as it was, and nothing that I say is to minimize how terrible antebellum slavery was. But the economic incentives of that system explicitly encouraged the preservation of slaves, because a slave owner had invested large sums of money in the acquisition of a slave. And then they wanted the slave to live as long as possible both so they would have the productivity of them as a worker, but also so that they would procreate, and there would be more slaves, which would add to the value of the assets of the farm. This was the fundamental economic formula of antebellum slavery. There was also a sense in the religious beliefs that were prevalent at the time that god had ordained slavery, but that white men had some obligation nonetheless to care for this lower species, and this is something that whites were routinely taught every Sunday morning.

Well, in the new slavery that emerged after the Civil War—it actually had its beginnings in an experiment with industrial slavery that had begun in the Deep South just before the Civil War, when a handful of industrialists had begun to experiment with using Black slaves in settings like iron foundries and sawmills and coal mines and other of these coarse industrial activities. That was extremely profitable for those slave owners before the Civil War. And they began to realize one of the reasons it was so profitable was that when you removed Black men from family settings and took the view that as long as the enterprise has received a return on its investment within four or five years by working these men at a pace far beyond what any human being could be expected to survive, then you could begin to make a profit off of these men in a relatively short period of time. And if they then died, or were worked to death, that that was a reasonable bargain in the economic equation of industrial slavery.

Well that process was stopped by the Civil War. But after the war, some of the very same men were the leaders of the effort to begin re-engineering this new kind of neo-slavery after the Civil War. And as it metastasized across the South at the end of the 19th century and into the 20th century, this much more brutal, more harsh form of slavery was endemic. There were few women in the picture. It was overwhelmingly focused on young Black men. And they were routinely worked to death or put into positions where their death was likely or probable, and because it cost so little to acquire them through the judicial system, through the fake judicial systems that emerged to feed this traffic in humans, there was little incentive to protect these workers in any way, and they rarely were protected.

Slate: When you're talking about the Civil War, you mention something that it's really important for people to keep in mind, that the Civil War actually was a war between the slave system and capitalism. And there was actually a moral component of it in that people actually were taking a stand that slavery was wrong and shouldn't exist, but then, along with a lot of other things in the superstructure, there was a reassessment of the Civil War that actually went along with the birth and implementation of this neo-slavery. When slavery was defeated as the dominant economic system in the South, there was this need to industrialize the South, to fully bring capitalism into the South. Also you had the growth of the need to expand of capitalism generally in the country, and a lot of this tied into—when you mentioned U.S. Steel it made me think of this—the existence of this neo-slavery in the South.

Blackmon: That's right on several fronts there. One of the interesting things to me as I tried to plumb these phenomena in the course of the seven years of research that I did on this while doing a few other things too, but I spent a lot of time trying to understand why it was that in the aftermath of slavery, of the Civil War, and especially after a period of time in which there actually had been a fair amount of successful Black and white interactions politically in the South, as in fact there was in many places for a period of time after the Civil War, but why was it that, in spite of all of that, and in spite of the fairly obvious moral rectitude of having ended slavery once it had finally come about, why was it that there was so much venom and animosity among white southerners and such an insistence to begin returning to some kind of forced slavery?

One of the things that became clear to me as I studied what was happening on cotton farms and in other settings across the South, was that number one, the southern economy and in some respects the national economy, were addicted to forced slavery. White southerners really had no idea how to grow cotton without the availability of armies of forced Black workers to do that work, both in terms of the need for manual laborers and the intellectual knowledge that was necessary to deploy those laborers in the setting of cotton farms and even in industrial settings. This addiction to forced labor was so great that there was this enormous compulsion to return to it.

But in the end it's perhaps not all that surprising that white southerners conducted themselves in the way that they did in terms of their ability to mete out such violence and depravity, really, against African Americans—maybe that's not such a surprise. But what was shocking to me as I began to understand it better, was the degree to which whites outside the South, whites all over the country, began to reassess the Civil War, began to reassess the mythology of the Civil War that had viewed it as a war of liberation and emancipation, and began to instead be driven by a sense that the integration of slaves and their children and grandchildren into mainstream American society was simply too hard and was not worth the effort. Even Ulysses Grant, the great Union general, during his presidency in the 1880s, confided to a member of his cabinet that he had come to realize that the Fifteenth Amendment, which gave full citizenship to freed slaves, had been a mistake. And by the end of the 19th century, when President McKinley was assassinated in 1901, and McKinley was the last Union officer to hold the presidency, and the generation that had made up the Union army and that army of liberation had become a geriatric generation who were passing from the national stage. When Teddy Roosevelt becomes president as a result of that assassination in 1901, he enters the White House as an idealist very committed to rights for Blacks, but by the end of his presidency, he, along with the vast majority of white Americans in every region of the country, has turned completely against the idea that Blacks should be guaranteed a full place at the table of American life and American citizenship.

For me that was one of the most remarkable aspects of coming to understand the sequence of events. There was this great betrayal of southern Blacks by their former allies outside of the South.

Slate: The other part of that question was about the expansion, the accumulation of capital and the profitability of this neo-slavery for the growth of this system.

Blackmon: Particularly at the end of the 19th century when you had this explosion in parts of the South, like Alabama, northern Georgia, and the coastal areas of the South where there were these huge forests of pine trees, mostly virgin timber, millions of acres of virgin pine forests where there was an enormous industry of harvesting pine rosin from the trees that was then distilled into turpentine. In some respects that was as important a commodity to the U.S. economy in the 1900s as gasoline is today. That's a slight exaggeration, but not much of one. It was an incredibly lucrative business that involved thousands and thousands and thousands of people and millions of dollars. And all of those enterprises, particularly in the South, were incredibly reliant, as was railroad building, another one of the main ones, all of those enterprises and industries were overwhelmingly dependent on the use of forced labor, and also the existence of a forced labor system to depress the wages of free laborers. Those were incredibly important phenomena of the economic revitalization and industrialization of the South. Many of the fortunes that were accumulated at that point in time, particularly in cities like Atlanta, where I live, some of the most prominent families and most prominent publicly traded corporations that exist today, their roots are either explicitly connected to this kind of forced labor, or the wealth that was used to build those companies such as Coca-Cola company and many others, the wealth that flowed to create those corporations stemmed originally from these forced labor practices.

Slate: You talked about the use of the courts in enslaving people. But you had the 13th, 14th, 15th amendments. You had what people would assume would be various federal legal remedies to this. What was actually the story in terms of being able to go to the courts to stop this kind of stuff?

Blackmon: The real story was that while slavery was unconstitutional on the basis of the Thirteenth Amendment, and clearly it was explicitly the case that no state could pass laws to recreate a formal system of slavery, no person could hold a deed showing that they owned a person as a slave and file that deed at the courthouse. That clearly could not happen. That was unconstitutional. But the Congress had never taken the next step, the next logical step, of passing a criminal statute which made it explicitly a crime to enslave another person. There were laws on the books that could have been used to prosecute someone for holding a slave, such as kidnapping and similar laws, but at that time, those were all state offenses and could only have been prosecuted by state officials like a county sheriff or the attorney general of a southern state.

But the reality was, no southern state would ever bring a case or such charges against a white man in the South. And no white jury in the South under almost any circumstances, would convict a white man for that. And so it created this kind of legal limbo in which slavery was unconstitutional, but there was no federal statute which actually made it a crime to hold slaves. So as the years went by, and thousands and thousands of complaints poured into the White House, and into the Department of Justice in Washington describing instances all over the South—there are 30,000 pages of material related to these complaints in the National Archives today—and as these thousands and thousands of complaints poured in as the years went by, the policy of the federal government was that there wasn't a statute on which a U.S. attorney could bring a case against a person for holding slaves, except in very narrow circumstances. So the policy of the federal government was that it would not involve itself in investigations or prosecutions of individuals who were still holding slaves in the South.

That was the policy of the federal government all the way until December 11, 1941.

Slate: Let's end with that, because it is stunning, the bald-faced cynicism that finally brought an end to this semi-officially-sanctioned slavery.

Blackmon: It is cynical. What finally brought things to an end was that on December 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. As the next President Roosevelt is engaging the government to mobilize for a massive war, he gathers his cabinet and asks them all to give a report on the critical issues that face the war mobilization effort. And one topic that comes up is propaganda, and what are the propaganda vulnerabilities of the United States? Someone in the room, there is no record of who, says that the United States is going to have trouble over its treatment of African Americans in the South, and that the Japanese would argue in their propaganda, which was the case eventually, that America was not the country fighting for freedom, and that the proof of that was in its treatment of Blacks in the South. So Roosevelt immediately orders that an anti-lynching law be drafted and introduced in the Congress. It was still many years before such a law actually passed the Congress.

But subsequent to this meeting, the attorney general at this time, Francis Biddle, went back to his own office, asked the same questions of his immediate deputies, and one of his deputies says, yes, lynching is a big issue, but it's also a problem, you're going to find it hard to believe this Mr. Attorney General, but there are places in the South where slaves are still being held, and it has been the policy of our department not to prosecute cases against those people. The attorney general is shocked initially, but then asks for a memo on how to prosecute such cases under laws which did exist. Four days later, on December 11, he distributes a memo to all U.S. attorneys essentially saying that this has come to his attention and instructing them that from that day forward they should prosecute cases and giving them a sort of cheat sheet on how to attempt to do that. And in 1942, just a few months later, a family near Corpus Christi, Texas, a man and his adult daughter, are arrested and charged under the new policy of prosecuting these cases, and they're tried later in 1942, and convicted. In 1943, they're sentenced to prison for having held a man named Alfred Irving as a slave for more than five years. I mark that as the technical end of the age of neo-slavery.

No comments:

Post a Comment