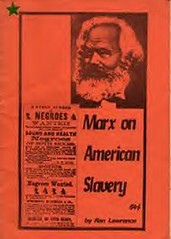

Karl Marx wrote on the American enslavement of the African people as well as the US civil war. Slave labor created the profits that fueled industrial capitalism.

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire File Photos

by Ken Lawrence

1972

Throughout Karl Marx's long career as philosopher, historian, social critic, and revolutionary, he considered the enslavement of African people in America to be a fundamental aspect of rising capitalism, not only in the New World, but in Europe as well.

As early as 1847, Marx made the following forceful observation:

Direct slavery is just as much the pivot of bourgeois industry as machinery, credits, etc. Without slavery you have no cotton; without cotton you have no modern industry. It is slavery that has given the colonies their value; it is the colonies that have created world trade, and it is world trade that is the pre-condition of large-scale industry. Thus slavery is an economic category of the greatest importance.

Without slavery North America, the roost progressive of countries, would be transformed into a patriarchal country. Wipe out North America from the map of the world, and you will have anarchy — the complete decay of modern commerce and civilisation. Cause slavery to disappear and you will have wiped America off the map of nations.

Thus slavery, because it is an economic category, has always existed among the institutions of the peoples. Modern nations have been able only to disguise slavery in their own countries, but they have imposed it without disguise upon the New World.[1]

Marx's view of slavery was not static. Like all other exploitative social systems, Marx viewed modern slavery as a system with a dynamic rise as productive forces developed, followed by stagnation, decline and overthrow. Most importantly, it was a society which created the seeds of its own destruction — the contending classes which stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary re-constitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes.[2]

In order to clearly understand Marx's views on American slavery, it is important to distinguish between two different social systems treated by Marx, both of which are called "slavery." One is ancient slavery, a social system through which almost all peoples came during the formative years of civilization; the other is the slavery which accompanied the emergence of capitalism, generally featuring the enslavement of Africans in North and South America and the Caribbean.[3] In this essay, except for aspects common to both, we are only concerned with the latter.

Both of these systems are characterized by the exploitation of human chattels. But the differences Marx noted between pre-capitalist slavery and the slavery that developed within capitalist society, particularly in the Southern United States, were profound.

In 1857 Marx wrote that the United States was a country where bourgeois society did not develop on the foundation of the feudal system, but developed rather from itself; where this society appears not as the surviving result of a centuries-old movement, but rather as the starting-point of a new movement; where the state, in contrast to all earlier national formations, was from the beginning subordinate to bourgeois society, to its production, and never could make the pretence of being an end-in-itself; where, finally, bourgeois society itself, linking up the productive forces of an old world with the enormous natural terrain of a new one, has developed to hitherto unheard-of dimensions and with unheard-of freedom of movement, has far outstripped all previous work in the conquest of the forces of nature, and where, finally, even the antitheses of bourgeois society itself appear only as vanishing moments.[4]

The development of the United States, however, was bound up with events in Europe, particularly England, as Marx noted in CAPITAL:

Whilst the cotton industry introduced child-slavery in England, it gave in the United States a stimulus to the transformation of the earlier, more or less patriarchal slavery, into a system of commercial exploitation. In fact, the veiled slavery of the wage-earners in Europe needed, for its pedestal, slavery pure and simple in the New World.[5]

Frederick Engels made the same point: Slavery in the United States of America was based far less on force than on the English cotton industry; in those districts where no cotton was grown or which, unlike the border states, did not breed slaves for the cotton-growing states, it died out of itself without any force being used, simply because it did not pay.[6]

It is true that even though Marx considered slavery "just as much the pivot of bourgeois society as machinery," as we have seen, he nevertheless devoted more of his writing to machinery. That is probably because he thought that "the history of the productive organs of man" would be the history "of organs that are the material basis of all social organization." Yet, at the time he wrote CAPITAL, Marx lamented that "Hitherto there is no such book."[7]

Because Marx devoted so much attention to the development of machinery as the basis of the industrial revolution, particularly the inventions that created and advanced the cotton industry in the 18th century — the spinning jenny, the power loom, the steam engine, the saw gin, the steamboat[8] — it is easy to forget that he saw the origin and development of capitalist production much earlier:

Although we come across the first beginnings of capitalist production as early as the 14th or 15th century, sporadically, in certain towns of the Mediterranean, the capitalistic era dates from the 16th century.[9]

Capitalism in agriculture follows the development of industry:

Historically too, as the capitalist mode of production appears later in agriculture than in industry, agricultural profit is determined by industrial profit, and not the other way about.[10]

And once industrial capitalism becomes dominant, agriculture is forcibly transformed also: In the period of the stormy growth of capitalist production, productivity in industry develops rapidly as compared with agriculture, although its development presupposes that a significant change as between constant and variable capital has already taken place in agriculture, that is, a large number of people have been driven off the land. . . . when industry reaches a certain level the disproportion must diminish, in other words, productivity in agriculture must increase relatively more rapidly than in industry. This requires . . . the replacement of the easy-going farmer by the businessman, the farming capitalist; transformation of the husbandman into a pure wage laborer; large-scale agriculture, i.e. with concentrated capitals.[11]

Rearranging and summing up the terrain we have covered so far, we can draw the following sketch from Marx's writings:

1) The capitalist era dates from the 16th century, and the beginnings of capitalism are even earlier.

2) The capitalist mode of production appears first in industry, later in agriculture — therefore agricultural profit is determined by industrial profit.

3) Even though capitalism in agriculture is economically subordinate to industry, the development of each is intertwined with the other.

4) The period of industry's "stormy growth" forces a transformation of agriculture into large-scale, capitalist enterprise.

5) Getting specific, two essential ingredients of the industrial revolution were (a) machinery, and (b) New World slavery -- because cotton was the basis of modern industry.

6) The rise of the cotton industry in England transformed slavery in the United States into a form of commercial exploitation.

Slavery was introduced in the New World, of course, in precapitalist times: In the precapitalist stages of society, commerce rules industry. The reverse is true of modern society. . . . Merchants' capital in its supremacy everywhere stands for a system of robbery, and its development, among the trading nations of old and new times, is always connected with plundering, piracy, snatching of slaves, conquest of colonies. ... In the antique world the effect of commerce and the development of merchants' capital always result in slave economy; or, according to what the point of departure may be, the result may simply turn out to be the transformation of a patriarchal slave system devoted to the production of direct means of subsistence into a similar system devoted to the production of surplus-value.[12]

The rise of commerce is not the entire reason for the development of slavery. According to Marx, the slave system preserves an element of natural economy. The slave market maintains its supply of labor-power by war, piracy, etc., and this rape is not promoted by a process of circulation, but by the natural appropriation of the labor-power of others by physical force.

Even in the United States, after the conversion of the neutral territory between the wage labor states of the North and the slave labor states of the South into a slave breeding region for the South, where the slave thus raised for the market had become an element of annual reproduction, this method did not suffice for a long time, so that the African slave trade was continued as long as possible for the purpose of supplying the market.[13]

A fundamental transformation takes place, however, when the capitalist market becomes dominant on a world scale: as soon as people, whose production still moves within the lower forms of slave-labor, courvee labor, etc., are drawn into the whirlpool of an international market dominated by the capitalistic mode of production, the sale of their products for export becoming their principal interest, the civilized horrors of over-work are grafted on the barbaric horrors of slavery, serfdom, etc.

Hence the Negro labor in the Southern States of the American Union preserved something of a patriarchal character, so long as production was chiefly directed to immediate local consumption. But in proportion, as the export of cotton became of vital interest to these states, the overworking of the Negro and sometimes the using up of his life in 7 years' of labor became a factor in a calculated and calculating system. It was no longer a question of obtaining from him a certain quantity of useful products. It was now a question of production of surplus-labor itself.[14]

This transformation, from production for direct consumption to production for the market (commodity production), causes violent crises in the economy of the producer during the transition from production for use to production for sale.[15]

We can summarize Marx's view of the transition from precapitalist to capitalist slavery as follows:

1) In the early period, merchants, not industrialists, dominate the rise of capitalism. This relationship generally results in a slave economy.

2) Later, when capitalist production — i.e., industry — becomes dominant, the international market serves to transform all forms of labor into commodity production.

3) Where a pre-capitalist form of labor, such as slavery, survives the transformation, the conditions of work are measurably worsened by the increased demand for surplusvalue (realized through sale), which replaces the precapitalist system of production for use alone.

4) The transformation causes violent economic crises.

Generally speaking, according to Marx, wage labor arises out of the dissolution of slavery and serfdom . . . and, in its adequate, epoch-making form, the form which takes possession of the entire social being of labor, out of the decline and fall of the guild economy, of the system of Estates, of labor and income in kind, of industry carried on as rural subsidiary occupation, of small-scale feudal agriculture etc. In all these real historic transitions, wage labor appears as the dissolution, the annihilation of relations in which labor was fixed on all sides, in its income, its content, its location, its scope etc. Hence as negation of the stability of labor and of its remuneration[16]

But that isn't always what happens. Slavery is also possible within the bourgeois system.

However, slavery is then possible there only because it does not exist at other points; and appears as an anomaly opposite the bourgeois system itself.[17]

The slave-holding states in the United States of North America . . . are associated with a world market based on capitalist production. No matter how large the surplus product they extract from the surplus labor of their slaves in the form of cotton or corn, they can adhere to this simple, undifferentiated labor because foreign trade enables them to convert these simple products into any kind of use-value.[18]

The fact that we now not only call the plantation owners in America capitalists, but that they are capitalists, is based on their existence as anomalies within a world market based on free labor.[19]

And slaves are proletarians.[20] Marx defines capitalism by its mode of production, but once that mode prevails, it consumes and dominates and transforms various other modes of production, including slavery, through its mode of circulation, because the process of production ends in a commodity. ... A commodity produced by a capitalist does not differ in itself from that produced by an Independent laborer, or by a laboring commune, or by slaves.[21]

The character of the process of production from which (commodities) emanate is immaterial. They perform the function of commodities on the market, and enter into the cycles of industrial capital as well as into those of the surplus-value carried by it.[22]

Summarizing some aspects of the transition from feudalism to capitalism, we have seen that Marx expressed these views:

1) Normally wage labor arises out of the dissolution of slavery and serfdom.

2) In some instances, slavery survives, as an anomaly.

3) Under these circumstances, the slave owners are capitalists, the slaves are proletarians, and the products of slave labor are commodities.

4) These commodities enter the cycles of industrial capital in the market; at the same time the slave-owning capitalists realize their surplus-value.

In his discussion of the working day, Marx quotes from J. E. Cairnes' book, THE SLAVE POWER, a passage where Cairnes says that the slave trade undermines the tendency toward humane treatment of slaves because "the duration of his life becomes a matter of less moment than its productiveness while it lasts. It is accordingly a maxim of slave management, in slave-importing countries, that the most effective economy is that which takes out of the human chattel in the shortest space of time the utmost amount of exertion it is capable of putting forth."

Marx adds that this is not a distinctive feature of slavery, since it characterizes the treatment of workers in England as well; he cites as examples the short- lived potters, bakers, and workers in the cotton industry, and shows that Manchester's system of obtaining workers from the agricultural districts "had grown up into a regular trade."[23]

Another aspect of slavery noted by many observers, a brutal spoliation of the soil, such as used to be In vogue among the former slave holders in the United States was not an essential ingredient. Marx noted that even if the landlord was an absentee, renting his property, ravaging the land was a thing against which the land owners may provide by contract.[24]

There are, however, some general aspects of the economics of capitalist slavery which were not directly analogous with the system of wage labor.

Take, for instance, the slavery system. The price paid for a slave Is nothing but the anticipated and capitalized surplus-value or profit, which is to be ground out of him. But the capital paid for the purchase of a slave does not belong to the capital, by which profit, surplus labor, is extracted from him. On the contrary. It is capital, which the slave holder gives away, it is a deduction from capital, which he has available for actual production. It has ceased to exist for him, just as the capital invested in the purchase of land has ceased to exist for agriculture.

The best proof of this is the fact, that it does not come back into existence for the slave holder or land owner, until he sells the slave or the land once more. Then the same condition of things holds good for the buyer. The fact that he has bought the slave does not enable him to exploit the slave without further ceremony. He is not able to do so until he invests some other capital in production by means of the slave.[25]

In most cases, the slave-owning capitalists owned land, slaves, and instruments of production (tools, mules, etc.).

In this case, the landlord and the owner of the instruments of production, and thus the direct exploiter of the laborers counted among these instruments of production, are one and the same person. Rent and profit likewise coincide then, there being no separation of the different forms of surplus-value. The entire surplus labor of the workers, which is here represented by the surplus product, is extracted from them directly by the owner of all the instruments of production, to which the land and, under the original form of slavery, the producers themselves, belong. Where capitalist conditions predominate, as they did upon the American plantations, this entire surplusvalue is regarded as profit.[26]

Although Marx viewed both slavery and wage labor, under capitalism, as forms of commercial exploitation, there were important specific differences between the two forms: as a slave, the worker has exchange value, a value; as a free wage-worker he has no value; it is rather his power of disposing of his labor, effected by exchange with him which has value. It is not he who stands towards the capitalist as exchange value, but the capitalist towatds him. His valuelessness and devaluation is the presupposition of capital precondition of free labor in general.[27]

In slave-labor, even that part of the working-day in which the slave is only replacing the value of his own means of existence, in which, therefore, in fact, he works for himself alone, appears as labor for his master. All the slave's labor appears as unpaid labor. In wage-labor, on the contrary, even surplus labor, or unpaid labor, appears as paid. There the property-relation conceals the labor of the slave for himself; here the money-relation conceals the unrequited labor of the wage-laborer.[28]

This was not simply a matter of appearances, either. The consequences of the differences were felt by the capitalists and the workers economically, because in the slave system, the advantage of a labor-power above the average, and the disadvantage of a labor—power below the average, affects the slave-owner; in the wage-labor system it affects the laborer himself, because his labor-power is, in the one case (wage labor), sold by himself, in the other (slavery), by a third person.[29]

One specific way in which the difference was felt was in the minimum wage.

It is characteristic in the determination of the minimum wage or the natural price of labor, that it is lower for the free wage-laborer than for the slave.[30]

Summing up this section, then, we see that Marx did not agree with some of his contemporaries that inhumane treatment was a unique characteristic of the slave system, nor that spoliation of the land was its necessary result. He did, however, discuss some economic realities which were peculiar to capitalist slavery:

1) The price of a slave is the anticipated profit "to be ground out of him."

2) Since the land owner and the exploiter of labor are the same person, there is no separation between different forms of surplus value — rent and profit coincide, and are simply considered profit.

3) A slave has value, exchange value. A free wageworker has no value, only the power to dispose of his labor.

4) All of the slave's labor appears to be unpaid; the property-relation conceals the labor of the slave for himself.

5) All of the free worker's labor appears to be paid; the money-relation conceals the labor of the worker for the capitalist — the surplus labor.

6) Economically, the slave owner, not the slave, is affected by the advantage or disadvantage of an individual slave compared to the average.

7) Conversely, under the wage-labor system, it is the worker who is affected by the advantage or disadvantage.

8) The minimum cost of maintaining a slave is higher than the minimum wage of a free wage-laborer.

Changing conditions of the capitalist market on a national and world scale created the economic preconditions for the overthrow of slavery. As we noted earlier, Marx considered slavery in North America to be absolutely essential to world capitalism in 1847.

Writing in 1885, Engels commented, this was perfectly correct for the year 18A7. At that time the world trade of the United States was limited mainly to import of immigrants and industrial products, and export of cotton and tobacco, i.e., of the products of southern slave labor. The northern states produced mainly corn and meat for the slave states. It was only when the North produced corn and meat for export and also became an industrial country, and when the American cotton monopoly had to face powerful competition, in India, Egypt, Brazil, etc., that the abolition of slavery became possible. And even then this led to the ruin of the South, which did not succeed in replacing the open Negro slavery by the disguised slavery of Indian and Chinese coolies.[31]

This changing alignment of forces nationally created a crisis for the slave-owning capitalists, for two reasons:

(1) by dint of an economical law, American slavery was doomed to gradual extinction from the moment it should be deprived of its power of expansion. That "economical law" was perfectly understood by the slavocracy. . . . (2) Quite apart from the economical law which makes the diffusion of slavery a vital condition for its maintenance within its constitutional areas, the leaders of the South had never deceived themselves as to the necessity for keeping up their political sway over the United States.[32]

According to Marx's analysis, they were doomed.

If the positive and final result of each single contest told in favor of the South, the attentive observer of history could not but see that every new advance of the slave power was a step forward to its ultimate defeat.[33]

In 1861 the struggle over slavery in the United States reached the point of no return, "the matured result of long years of struggle." Marx called this struggle "the moving power of its history for half a century."[34]

The violence of the crisis cannot be explained simply by noting the need of the industrial capitalist class to rid itself of a fetter. The crisis of two forms of capital emerged against a backdrop of violent, uninterrupted class struggle: . . . the antagonism between the laborer as a direct producer and the owner of the means of production . . . reaches its maximum in the slave system.[35]

This explains why Marx vas not only a supporter of the Union, but at the same time one of its sharpest critics, demanding abolition and the arming of the freedmen.[36]

Marx recognized a unity of class interest among slaves and freedmen, white workers of the North, and English workers. He believed that only the workers, by virtue of their strength in numbers, could defeat slavery. Thus he referred to "the workingmen" as "the true political power of the North."[37] But while he rallied workers to the causes of abolition, nonintervention, and Union, he did not deceive himself about the fact that the workers did not always act in the interest of their class.

In his correspondence with Engels, Marx analyzed not only the problems with the bourgeoisie's conduct of the war, he also faced squarely the hesitancy of the white workers in carrying out their duties as a class.[38] Publicly he proclaimed the same thing, that it was the white workers who allowed slavery to defile their own republic; while before the Negro, mastered and sold without his concurrence, they boasted it the highest prerogative of the white-skinned laborer to sell himself and choose his own master; and they were unable to attain the true freedom of labor or to support their European brethren in their struggle for emancipation, but this barrier to progress has been swept off by the red sea of civil war.[39]

Because the white workers boasted their status as free laborers as "the highest prerogative," Marx viewed this as the Achilles heel of the labor movement, and the sweeping away of this "barrier to progress" as the essential precondition for an effective, independent workers' movement in the United States.

In the United States of North America, every independent movement of the workers was paralyzed so long as slavery disfigured a part of the Republic. Labor cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the black it is branded. But out of the death of slavery a new life at once arose. The first fruit of the Civil War was the eight hours' agitation, that ran with the seven-leagued boots of the locomotive from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from New England to California.[40]

In a letter to Engels on April 23, 1866, Marx wrote, "after the Civil War phase the United States are really only now entering the revolutionary phase,"[41] and less than a year later he noted the international importance of that struggle.

As in the 18th century, the American war of independence sounded the tocsin for the European middle-class, so in the 19th century, the American civil war Bounded it for the European working-class.[42]

Thus Marx viewed the final fifty years of the slaves' struggle for freedom in the United States not simply as an attempt to throw off an antiquated labor system. He saw the emancipation struggle as the most advanced outpost of labor's fight against capital; its success placed proletarian revolution at the top of the world's political agenda.

Tougaloo, Mississippi

First draft June 1, 1975

Second draft November 26, 1975

Editorial note: Throughout this essay, quoted material has been altered, when necessary, to conform to contemporary capitalization and spelling usage in the United States.

FOOTNOTES

1. Karl Marx, The Poverty of Philosophy: A Reply to M. Proudhon’s Philosophy of Poverty, New York, International Publishers, n.d., pages 94-5.

2. Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Communist Manifesto, Chicago, Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1947, page 12.

3. "Needless to say we are dealing only with direct slavery, with Negro slavery in Surinam, in Brazil, in the Southern States of North America." Marx, Poverty of Philosophy, page 94.

4. Karl Marx, Grundrisse., Middlesex, Penguin Books, 1973, page 884. Later, Marx qualified this view, but only slightly, when he referred to the United States "where originally land has not been appropriated and where, at any rate in a_ formal sense, the bourgeois mode of production prevails from the beginning." Karl Marx, Theories of Surplus Value, Part II, Moscow, Progress Publishers, 1968, page 42. (Emphasis added.)

5. Karl Marx, Capital, Volume I, Chicago, Charles Kerr & Co., 1906, page 833.

6. Frederick Engels, Anti-Duhring, Moscow, Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1959, pages 222-3.

7. Marx, Capital I, page 406.

8. Ibid., pages 406-419.

9. Ibid., page 787.

10. Marx, Theories of Surplus Value, Part II, page 467.

11. Ibid., page 110. (Marx's emphasis.)

12. Karl Marx, Capital, Volume III, Chicago, Charles Kerr & Co., 1909, pages 389-391.

13. Karl Marx, Capital, Volume II, Chicago, Charles Kerr & Co., 1909, page 559.

14. Marx, Capital I, page 260.

15. Marx, Capital II, page 159. (footnote)

16. Marx, Grundrisse, page 891. (Marx's emphasis.)

17. Ibid., page 464. Marx discussed this phenomenon in his preface to the first edition of Capital: "Alongside of modern evils, a whole series of inherited evils oppress us, arising from the passive survival of antiquated modes of production, with their inevitable train of social and political anachronisms. We suffer not only from the living, but from the dead." Marx, Capital I, page 13. After a time, the antiquated modes aren't always so anachronistic: "Taking the exchange of commodities as our basis, our first assump- tion was that capitalist and laborer met as free persons, as independent owners of commodities; the one possessing money and means of production, the other labor-power. But now the capitalist buys children and young persons under age. Previously, the workman sold his own labor power, which he disposed of nominally as a free agent. Now he sells his wife and child. He has become a slave dealer. The demand for children's labor often resembles in form the inquiries for Negro slaves, such as were formerly to be read among the advertisements in American journals." Marx, Capital I, pages 432-3.

18. Karl Marx, Theories of Surplus Value, Part III, Moscow, Progress Publishers, 1971, page 243.

19. Marx, Grundrisse, page 513. (Marx's emphasis.) He explicitly described the anomaly as follows: In plantation colonies "where commercial speculations figure from the start and production is intended for the world market, the capitalist mode of production exists, although only in a formal sense, since the slavery of Negroes precludes free wage-labor, which is the basis of capitalist production. But the business in which slaves are used is conducted by capitalists. The method of production which they introduce has not arisen out of slavery but is grafted on to it. In this case the same person is capitalist and landowner." Marx, Theories of Surplus Value, Part II, pages 302-3. (Marx's emphasis.)

20. Here it does not matter which period we are discussing: "Feudalism also had its proletariat — serfdom. . . . The bourgeoisie begins with a proletariat which is itself a relic of the proletariat of feudal times." Marx, Poverty of Philosophy, page 103-4.

21. Marx, Capital II, page 446.

22. Ibid., page 125.

23. Marx, Capital I, pages 292-4.

24. Marx, Capital III, page 726.

25. Ibid., page 940.

26. Ibid., page 934.

27. Marx, Grundrisse,, pages 288-9. (Marx's emphasis.)

28. Marx, Capital I, page 591.

29. Ibid., page 593.

30. Marx, Theories of Surplus Value, Part II, page 225. This statement should be interpreted cautiously, In order to avoid reading into it Ideas which were not held by Marx. In the passage cited, Marx is discussing (approvingly, in this case) an observation made by Adam Smith in An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Both Smith and Marx agree that the minimum wage is equal to subsistence — the "fund" for replacing or repairing the "wear and tear" of the slave or free worker, in Adam Smith's words. They also agree that this "fund" is "used frugally by the free laborer whereas for the slave it is wastefully and disorderly administered" because the slave "is commonly managed by a negligent master or careless overseer." Thus neither Marx nor Smith claims that what the slave actually gets, as a minimum, exceeds the minimum wage of the free worker.

31. Marx, Poverty of, Phito&ophy, pages 94-5. (Footnote by Engels.)

32. Karl Marx, "The American Question in England," in New York Daily Tribune,, October 11, 1861. Reprinted in Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, The Civil War in the United States, New York, International Publishers, 1961, page 11. (Marx's emphasis.)

33. Ibid., page 6.

34. Ibid., page 8. (Emphasis added.)

35. Marx, Capital III, page 451. "It is characteristic that, in general, real forced labor displays in the most brutal form, most clearly the essential features of wage-labor." Marx, Theories of Surplus Value, Part III, page 400. (Marx's emphasis.)

36. For examples see Marx and Engels, Civil War, pages 82, 198-206, 253.

37. Ibid., page 280.

38. Ibid., pages 261-2.

39. Ibid., pages 280-1.

40. Marx, Capital I, page 329.

41. Marx and Engels, Civil War, page 277.

42. Marx, Capital I, page 14.

No comments:

Post a Comment