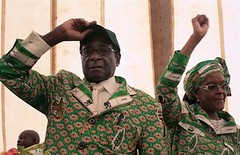

Zimbabwe President Robert Mugabe and first lady Grace Amai, greeting the delegates at the ZANU-PF national conference on December 19, 2008.

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire File Photos

Herald Reporters

THE International Monetary Fund has partially lifted the suspension of technical assistance to Zimbabwe in recognition of the country’s co-operation on reforming economic policies.

THE International Monetary Fund has partially lifted the suspension of technical assistance to Zimbabwe in recognition of the country’s co-operation on reforming economic policies.

In a statement released on Wednesday following Monday’s IMF executive board meeting, the Bretton Woods institution said it would examine the decision at the next review of Zimbabwe’s financial obligations.

"Effective from May 4, 2009, IMF technical assistance can be provided to Zimbabwe in the areas of tax policy and administration, payment systems, lender-of-last-resort operations and banking supervision and central banking governance and accounting," the statement said.

The decision will be analysed at the next review of Zimbabwe’s obligations to the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility-Exogenous Shock Facility Trust and at subsequent six monthly reviews.

The half-yearly reviews will be held for as long as Zimbabwe is in arrears to the Trust.

"In taking this decision, the Executive Board took into account a significant improvement in Zimbabwe’s co-operation on economic policies to address its arrears problems and severe capacity constraints in the IMF’s core areas of expertise that represent a major risk to the implementation of the Government’s macro-economic stabilisation programme," the institution said.

Zimbabwe owes about US$133 million to the PRGF-ESF Trust which led to the suspension of technical assistance to the country.

The IMF has already hailed Government’s efforts to revive the country’s economy through the Short-Term Emergency Recovery Programme.

However, Finance Minister Tendai Biti — who attended the IMF and World Bank spring meetings in Washington, DC — said STERP would fail if the United States government maintained its illegal sanctions law, the so-called Zimbabwe Democracy and Economic Recovery Act of 2001.

According to ZDERA, the US Secretary of the Treasury is instructed to ensure any American executive director at an international financial institution opposes and votes against any extension by the respective institution of any loan, credit or guarantee to Zimbabwe.

The British government, which advocated sanctions against Zimbabwe following a bilateral dispute over land, has said it will no longer vote against IMF, International Finance Corporation and World Bank funding to Zimbabwe.

Minister Biti yesterday met with ambassadors based in the country to apprise them on his recent trip to America.

The meeting, which was called for by the ambassadors, also discussed issues related to finance requirements under STERP.

Under STERP, Minister Biti said he gave the ambassadors a micro-breakdown of the requirements of each sector.

He said that brief focused on the complete breakdown of what the requirements are.

"For instance, in terms of water and sanitation, we require US$225 million and that money is needed to buy filters, water pumps and other accessories and it is that breakdown that we were giving them.

"We want the ambassadors to look at the requirements and see where they can come in," he said.

Minister Biti said they also discussed issues related to the multi-donor trust fund.

The country requires at least US$8 billion to fund its activities under STERP that is expected to kick-start the economic recovery process.

The country has so far received US$650 million in lines of credit from Botswana, South Africa, Comesa and the PTA Bank.

Congratulations to Zuma, ANC

EDITOR — The South African elections have come and gone.

Tomorrow, Cde Jacob Zuma will be inaugurated as the third president of the independent Republic of South Africa.

As a revolutionary, I wish to extend my deepest congratulations to Cde Zuma, the ANC and the people of South Africa, for the dawn of yet another new era.

I was gratified to hear that one of the five key areas that the Zuma presidency will concentrate on will be land reform.

What lessons will South Africa draw from Zimbabwe’s Land Reform Programme?

I also wish to congratulate the "mother of the nation", Cde Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, for bouncing back into the political limelight.

You had become so quiet sister!

The bumpy road you traversed is well acknowledged by many, and we wish that you continue to contribute positively to the development of South Africa and Africa as a whole.

Varaidzo Ziyambe.

Harare.

Monetary union vital for Africa

By Mammo Muchie

TWO obstacles prevent Africa from entering the phase of self-reliant development: irrational fragmentation from a casual tearing-up of the continent into incoherent real estates of the African peoples, and dependence on donors to finance African development.

The first emanates from monumental historical-political crimes that saw Africa divided according to the whims of colonial powers.

This demands rectification by making the boundaries innocuous to Africa’s peoples through allowing voluntary and free movement of people.

The second is to create a unified African strategy and approach to dealing with the outside donor world by neutralising the poison that donor aid has come to be in Africa. Weak and fragmented states, largely unable and not often in a position to mobilise internal resources, depend on external sources of aid.

Political fragmentation has created unviable economic entities.

Conversely, lack of success in economic development has created weak political structures and so-called failed States that fall prostrate with begging bowls.

Africa’s position as a donor recipient bolsters donor agencies, accentuates inter-African fragmentation and destroys the chance to evolve a unified African strategy.

Donor econocentrism destroys Africa’s logocentric imagination, vision and strategy to evolve a unified and Africa-centred development.

The G8 meeting in Gleneagles promised US$50 billion and remains unfulfilled.

The grand lesson is this: Africans must rely on Africans and must build their unity to own their mineral and agricultural wealth and manufacture that into value-added wealth.

Africa’s new relationship with the rest of the world will be born when Africans learn to neutralise the harm that the unholy trinity of loans, aid and debt has done to them.

One key initiative is to establish a currency system that can largely self-finance an integrated African development.

The existing State currencies that are not exchanged directly with each other, and whose exchange rate is mediated with the dollar, the franc and the euro, should give way to direct exchanges based on a fair settlement.

Naturally, diversities, inequalities, different levels of development, differing attitudes and interests present problems in constructing a workable unified currency system.

It is precisely to deal with these varied problems that Africa needs a currency system to create liquidity.

The exchange of the local-to-local currency via a global currency continues to fragment Africa and integrate discrete interests and regions with the world economy.

The key is to find strategies for Africa to integrate with the world economy as a whole and not in parts.

The domestication of the existing national currencies is necessary to make Africa relink with the world economy on its own terms and not terms dictated by others.

The move must be sensible, realistic and inclusive.

If the cost and benefits for the various sections of social groups can be fairly worked out, possibilities exist even to neutralise transnational, supranational actors, who will no doubt be worked up by the suggestion for a monetary union.

There are innumerable informal, spontaneous and voluntary cross-border transactions in Africa. Those engaged in such transactions would prefer exchanging their goods for hard currencies such as dollars or francs.

This is often related to the pegging of local currencies to the US dollar and French franc.

An African currency that can serve as a sort of local dollar or franc will stimulate the domestic market and communication among African regions, peoples, communities, markets and states.

The unified currency will assist gradually to overcome the limitation of many weak currencies with new money serving as a unit of account, a store of value, means of payment and means of circulation convertible within Africa.

African economies continue to import and export vertically and not horizontally.

This structure reflects a largely unchanged trade pattern between Africa’s primary products and manufactured products from the Western world.

Economic diversification is still a job waiting to be done.

The weakness of African currencies is tied to the lack of a diversified economic structure.

The price of foreign money is high compared to the price of local money.

For example, the French franc used to be 100 times the local CFA franc in West and Central Africa.

One euro is CFA 665,957. Now the franc is dead in France replaced by the euro and is alive in West and Central Africa!

Tourists and real estate dealers with French francs or euros can purchase services and local assets in Africa with a couple of thousands of these notes.

African exports should be cheaper, but with so many tariff barriers to Africa’s primary and semi-manufactured goods and worsening terms of trade, and unchanging commodity portfolios, the advantage of devalued local currencies is neutralised.

Africa in the CFA zone largely loses both in its exports and imports based on the existing arrangements.

Money and financial flows still occur between Africa and the West rather than within Africa itself. Inter-African integration, mobility of money, labour and capital is more difficult than the movement of money, people and capital within African states.

This pattern has been reinforced by Africa’s dependence on loans, grants and debt.

When debt repayment becomes a priority, the political economy of the interests of the international financial institutions (IFIs) becomes paramount.

When improvement of the standard of livelihood of the population is a priority, social spending will be necessary to bring it about.

However, despite the rhetoric by the IFIs as "friends of the poor" following policies of poverty reduction, loans through such schemes as the heavily indebted poor countries schemes, policies of structural adjustment have been followed, in reality, at the expense of social spending for development. Africa has been confronted with a stark constraint: a policy structure that has privileged debt repayment over development.

International politics and economics have forced this policy choice over a Pan-African alternative.

To maintain or to change this policy structure is an important issue confronting Africa in the 21st century.

The Pan-African quest is to change the African situation, while the IFIs want to retain the status quo of debt payment as a priority under the guise of the poverty reduction rhetoric.

Debt repayment distorts African economic policy in the direction of producing the things Africa cannot consume and to consume the things it cannot produce.

The advice from the international elite is to keep the capital account of African states open and unregulated.

This furthers the vulnerabilities of Africa’s economies to fall prey to cyclical fluctuations in the world economy.

They become easy victims to fast movements of speculative finance that episodically ravishes whole economies like gales.

The existing 53 State monetary arrangements in Africa are too fragmented to withstand powerful movements in world finance and business cycles. There has to be a creative way of breaking out of this trap for Africa.

We back-cast to look for any past attempts to forge currency unions in order to forecast feasible alternatives to get Africa going.

Prior to the programmatic call by Kwame Nkrumah to set up an African monetary union in May 1963, there have been a number of attempts to set up monetary unions in different regions of Africa.

The origin of the modern monetary unions is traceable to the colonial encounter between Europe and Africa.

The most enduring currency union has been that managed by France.

France planted the roots of the CFA franc zone in 1945.

This was the result of a decision by the French colonial government to crowd out the various local currencies and establish the franc as the sole legal tender throughout the French colonies of West and Central Africa.

France retained its control over the monetary arrangement of its West and Central African ex-colonies in the 60s by creating two regional currencies that cleverly retained the CFA franc designation in both regions.

The exchange rate between the ‘CFA francs of the West African Monetary Union and the Central African Monetary Area were made equal -- both maintaining the same parity against the French franc and capital can move freely between the two regions.

Both monetary areas have since comprised what France calls the "African Financial Community", where each currency is only legal tender in its own region, despite the currencies being jointly managed by the French Treasury as integral parts of a single monetary union.

Though France was not a member of the CFA itself, its Ministry of Finance held the operational accounts and the foreign exchange reserves of the central banks of West and Central Africa.

France insured convertibility of the CFA franc at a fixed price, set and controlled rules for credit withdrawal and maintained a ratio of 50:1 between the CFA franc and the French franc for half a century.

In 1994, there was a devaluation of the CFA franc to the French franc by a ratio of 100:1.

In January 1999, the CFA was pegged to the euro rather than the French franc, but in all other respects the French Ministry of Finance retained substantive control over the CFA franc zones.

The euro seems to have been introduced via France into West and Central Africa two years before 12 of its members began to use it as legal tender this year.

The British also had created a less successful East African Currency Board in 1919 and issued a common currency unit, the East African shilling, as legal tender in Kenya, Tanganyika (now Tanzania) and Uganda.

After independence in the 60s, the common currency area broke apart.

Efforts to mend the break-up are still continuing with the re-establishment of the East African Community.

During the 1920s, South Africa collaborated with the colonial powers to create a common monetary area.

The Common Monetary Area embraced South Africa, former British colonies Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland and the then German colony, Namibia.

After decolonisation in the late 60s, the Rand Monetary Area was formed in 1974, though diamond–rich Botswana was not in it preferring to set up the pula as national money.

It is interesting to note that more efforts were made during the colonial period to create currency unions than in the period of political independence.

The fact that Africa was diverted from following Pan-African directions in the post-colonial period meant that projects for currency unions to create liquidity to finance inter-African development were abandoned.

--Mammo Muchie is a professor at Aalborg University in Denmark and a member of the Network of Ethiopian Scholars. This article first appeared in The African Executive.

No comments:

Post a Comment