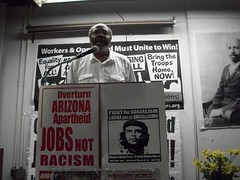

Abayomi Azikiwe, editor of the Pan-African News Wire, addressing the Black August commemoration in Detroit on August 7, 2010. (Photo: Andrea Egypt)

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire File Photos

From Jamestown to Detroit the struggle continues

By Abayomi Azikiwe

Editor, Pan-African News Wire

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Note: The following text are excerpts from an address delivered at the Detroit Black August commemoration held on August 7, 2010.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In August 1619, 20 Africans were brought into the Virginia colony of Britain in North America for the purpose of indentured servitude. Since that faithful day the question of the treatment of the descendants of these Africans, who would later be legally designated as slaves, has been a cornerstone of the failure of the United States to become a genuinely democratic country.

There were other indentured servants in the British colony at the time from Europe, yet their history would not lead to their descendants being designated as a permanent source of labor super-exploitation. The Africans along with the Native peoples, whose land was stolen in this process of settling Europeans in North America, provided the wealth that made this region of the world the leading imperialist state by the conclusion of World War II.

According to Logan and Cohen, “Beginning in 1640, however, most of the Negro servants brought into Virginia, had no indenture, and therefore could not look forward to receiving their freedom after a fixed period. They ceased to become bondsmen with limited rights and became personal property with no rights at all. This change—so crucial to our history—resulted from a number of conditions within English America.” (The American Negro, Rayford W. Logan and Irving S. Cohen, p. 43)

It was the status of the African people that led to revolts and an eventual civil war. A turning point took place when on August 30, 1800 an armed uprising broke out in Henrico County, Virginia under the leadership of a twenty- fouryear-old enslaved African named Gabriel. Some one thousand Africans had been organized for the revolt but word of the plans was leaked. The plan included a plot to set fire to the major plantations in the area. The plans also involved an operation leading to the kidnapping of the governor and demanding the abolition of slavery in exchange for his release.

Logan and Cohen recounts that “”However, two slaves informed the authorities. The revolt was crushed shortly thereafter when Governor Monroe called out the state militia to stop the rebels. Many slaves escaped but scores were captured. Thirty-six, including Gabriel, were executed. Though the slaves refused to talk to anyone, one made the following statement to his captors:

‘I have nothing more to offer than what General Washington would have had to offer, had he been taken by the British officers and put to trial by them. I have ventured my life in endeavoring to obtain the liberty of my countrymen, and am a willing sacrifice to their cause…. I beg as a favor that I may be immediately led to execution. I know that you have predetermined to shed by blood. Why, then, all this mockery of a trial?” (Logan and Cohen, p. 77)

In 1822, Denmark Vessey, who had purchased his freedom in 1800, was working as a carpenter while he engineered another plot for a slave rebellion that involved 9,000 people. Vessey had learned how to read and write and mastered several languages.

Vessey wrote to Haiti asking for assistance in the planned revolt. Unfortunately an informant revealed the plot to the slave owners and more than a hundred people were arrested. Later 47 people were executed in connection with the planned uprising.

Another noted slave rebellion that represented an advancement over the other two planned insurrections in 1800 and 1822, was the Nat Turner rebellion of 1831. Turner struck in South Hampton County, Virginia. Logan and Cohen say of this challenge to the slave system that “It proved to be one of the most violent rebellions of the period. In one day, Turner and his followers killed some sixty whites.” (Logan and Cohen, P. 77)

It took formidable forces of the state to subdue Turner and his comrades. Logan and Cohen say that “A pitched battle with state and federal troops cost the lives of more than a hundred slaves. Sixteen rebels, including free Negroes, were immediately hanged upon capture. Turner escaped capture for three months. He was finally tracked down by the authorities, brought to trial, and executed.” (p. 77)

The authors continue noting that “So shaken was the South by the Turner rebellion that several state legislatures, meeting in emergency session, passed new laws to restrict the slaves. Severe reprisals and stricter slave codes, however, failed to prevent rebellions. Slave uprisings continued to terrorize the South.”

Capitalism and the Slave System

One of the great inspirational figures of the Black Liberation Movement of the 1970s was George L. Jackson. He became known to the world as one of the Soledad Brothers housed in the California prison system during this period.

Jackson was charged with the murder of a guard and another inmate. Two of his comrades in Soledad Prison were also implicated in the murders. Jackson had been arrested in 1960 at the age of 18 for being in a car when co-passengers robbed a gas station of $70. Jackson became politicized in prison like so many other African American men from Malcolm X to Eldridge Cleaver.

Jackson was the co-founder of the Black Guerrilla Family in prison. He would later join the Black Panther Party and was appointed as Field Marshall. In 1970 he wrote of the slave system and its antecedents that in the United States “After the Civil War, the form of slavery changed from chattel to economic slavery, and we were thrown onto the labor market to compete at a disadvantage with poor whites.” (Soledad Brother, 1971, p. 175)

Jackson continued saying “Ever since that time, our principal enemy must be isolated and identified as capitalism. The slaver was and is the factory owner, the businessman of capitalist Amerika, the man responsible for employment, wages, prices, control of the nation’s institutions and culture. It was the capitalist infrastructure of Europe and the U.S. which was responsible for the rape of Africa and Asia.”

Therefore, Jackson saw clearly that there was a logical progression from the system of chattel slavery to industrial capitalism. He defines the struggle as one of both national oppression and class exploitation, but that the class struggle is the primary struggle.

Jackson notes that “Capitalism murdered those 30 million in the Congo. Believe me, the European and Anglo-Amerikan capitalism would never have wasted the ball and powder were it not for the profit principle. The men, all the men who went into Africa and Asia, the fleas who climbed on that elephant’s back with rape on their minds, richly deserve all that they are called. Every one of them deserved to die for their crimes. So do the ones who are still in Vietnam, Angola, Union of South Africa (USA!!).”

Nonetheless, Jackson emphasizes the need for an objective view of the enemy and the tactics needed to defeat capitalism and imperialism. It will require a scientific analysis of the problems facing the oppressed and a people’s organization to defeat it.

Jackson goes on to say that “we must not allow the emotional aspects of these issues, the scum at the surface, to obstruct our view of the big picture, the whole rotten hunk. It was capitalism that armed the ships, free enterprise that launched them, private ownership of property that fed the troops. Imperialism took up where the slave trade left off. It wasn’t until after the slave trade ended that Amerika, England, France, and the Netherlands invaded and settled in on Afro-Asian soil in earnest. As the European industrial revolution took hold, new economic attractions replaced the older ones; chattel slavery was replaced by neo-slavery. Capitalism, ‘free enterprise’, private ownership of public property armed and launched the ships and fed the troops; it should be clear that it was the profit motive that kept them there." (Soledad Brother, p. 176)

No comments:

Post a Comment