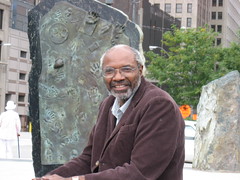

Abayomi Azikiwe, editor of the Pan-African News Wire, at the Labor Monument in Hart Plaza in downtown Detroit on September 27, 2008. (Photo: Alan Pollock).

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire File Photos

Why the current world struggle for revolutionary democracy is important for the future

By Abayomi Azikiwe

Editor, Pan-African News Wire

Events in Tunisia and Egypt have set off popular struggles for democracy throughout North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Since the eruption of mass demonstrations and rebellions in Tunisia resulting in the fleeing of the country by former President Ben Ali on Jan. 14, these uprisings have occurred in Yemen, Bahrain, Djibouti and other states throughout the region sparking solidarity actions globally and even influencing the workers’ struggle in the United States with people in Wisconsin occupying the capitol building making repeated references to the movement in Egypt.

Although, demonstrations have also occurred in countries which are considered enemies and less friendly to the United States, such as Iran, Sudan and Libya, the events in the pro-western states have typified the sentiment of people around the world who are suffering from the worst economic crisis since the 1930s. This economic crisis has its origins within the United States, where over 8 million jobs were lost over a period of two years from 2007-2009.

Not only have workers lost jobs at a phenomenal rate inside the United States, students have been forced to leave higher educational institutions. In the primary and secondary schools, youth have been subjected to the closing of academic and sports programs, the firing of teachers and the closing of neighborhood schools. Wisconsin may very well be the beginning of a new phase in the movement to reclaim the political agenda for the masses of working people and youth who are the most affected by the restructuring of world capitalism.

During the Great Depression of 1929-1941, millions of people were thrown out of work as well in the U.S. and in other industrialized countries. The left movements of the period would initiate coalitions to fight unemployment, evictions and racial violence. By 1930, the Unemployed Councils were formed to demand jobs and to put people back into their homes after they had been evicted by landlords.

The Roosevelt administration would incorporate socialist ideas of unemployment compensation, public works programs, support for farmers and government support for arts and literary projects as a means of both addressing the economic crisis and staving off a possible revolutionary movement for the seizure of power from the capitalist class. In 1934 general strikes took place throughout the country, the most notable being in Minneapolis and San Francisco.

In 1935, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) would be formed, pledging to organize workers of all races on a equal basis. African Americans would stand up that year opposing the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, where it could be argued the first battles of the Second World War took place on African soil.

Despite the strides made under the New Deal programs of Roosevelt and the organizing efforts of the labor movement, the left and the pan-african movement, it would only be the advent of World War II that would bring full employment to the United States between 1941-45. The war would necessitate the growing employment of African Americans and women in industrial production.

In the aftermath of World War II, the African American and other anti-colonial, pro-independence movements would gain further momentum and strength leading to the most profound challenges to the legacies of slavery, colonialism and monopoly capitalism throughout the entire 20th century. However, in order to understand the developments in the aftermath of World War II, we must first examine the significance of events that occurred in the aftermath of the First World War between 1914-18.

1919: Egypt Revolution, Race Riots and the Pan-African Movement

At the conclusion of World War I, a new upsurge in anti-colonial struggles would emerge. Some of the outstanding events of the period included the revolution in Egypt which resulted in the advancement towards national independence in 1922. Also the African American people would draw upon their legacy of resistance to slavery and Jim Crow by battling white racists and law-enforcement authorities during the Chicago Race Riot of the summer of 1919.

In Egypt, British imperialism had dominated the territory since at least the late 1800s when it built and took control of the Suez Canal. A racist colonial system of discrimination and national oppression was imposed upon the people of Egypt and neighboring Sudan.

Nonetheless, in the months following the conclusion of World War I, a nationalist movement would sweep both Egypt and Sudan opposing British colonial rule. At the Paris Peace Conference Egyptian nationalists such as Lutfi as Sayyid, Saad Zaghul, Muhammad Mahmud, Ali Sharawi, and Abd al Aziz Fahmi would appeal for full independence from Britain.

On November 13, 1918, the Day of Struggle, as it is known in Egyptian history, Zaghul, Fahmi and Sharawi held a meeting with the British High Commissioner to Egypt and demanded independence for Egypt and Sudan leaving the imperialists the option of still managing the Suez Canal and the public debt. (Armed Conflict Events Database, 2000)

A Wafd delegation was selected in early 1919 to travel to Britain to put forward their case for national independence. The British refused to allow the delegation to travel and on March 8, Zaghul along with three other members of the Wafd were detained by the colonialists and thrown into the Qasr an Nil prison.

They were soon deported to the Mediterranean island of Malta sparking a popular uprising in March and April of 1919. In a matter of days the rebellion had spread from Cairo to the provincial cities of Lower Egypt, in Tanta and further south resulting in pitch battles in Asyut Province in Upper Egypt.

In addition, student demonstrations were organized leading to strikes by government officials, professionals, women and transport workers. The entire country was shut down including the railroads, telegraph lines which were cut, while taxi drivers refused to work. Thousands demonstrated through the streets chanting pro-Wafdist slogans in favor of independence.

When the British attempted to crush the demonstrations with force, Egyptians fought back and killed many Europeans. One of the most significant features of the uprising of 1919 was the role of women.

According to the Armed Conflict Events Database, “On March 16, 1919, between 150 and 300 upper-class Egyptian women in veils staged a demonstration against the British occupation, an event that marked the entrance of Egyptian women into public life. The women were led by Safia Zaghul, wife of Wafd leader Saad Zaghul; Huda Sharawi, wife of one of the original members of the Wafd and organizer of the Egyptian Feminist Union; and Muna Fahmi Wissa. Women of the lower classes demonstrated in the streets alongside the men. In the countryside, women engaged in activities like cutting the rail lines.”

This account continues by pointing out that “The upper-class women participating in politics for the first time assumed key roles in the movement when the male leaders were exiled or detained. They organized strikes, demonstrations, and boycotts of British goods and wrote petitions, which they circulated to foreign embassies protesting British actions in Egypt.”

In fact the actions of the women on March 16 precipitated the largest demonstration of the 1919 Revolution when the following day over 10,000 teachers, students, workers, lawyers, and government employees set out in a march at Al Azhar and proceeded to Abdin Palace where they linked up with tens of thousands more who broke through roadblocks. The actions of March 17 would lead to other actions around the country.

The Armed Conflict Events Database says that “Soon, similar demonstrations broke out in Alexandria, Tanta, Damanhur, Al Mansurah, and Al Fayyum. By the summer of 1919, more than 800 Egyptians had been killed, as well as 31 Europeans and 29 British soldiers.”

Eventually the delegation was allowed to travel to Paris where they made a strong case for national independence before the post war imperialist states. It was eventually agreed to grant a unilateral declaration of independence to Egypt on February 22, 1922. However, Sudan was not included in the independence decree by the British and would have to wait until 1956 to gain its national independence from the U.K.

The African American National Question After World War I

After the collapse of the Reconstruction period in the United States, where the federal government and the Ku Klux Klan made an alliance denying the African American people the right to self-determination and social equality, many of the former slaves began to migrate to the urban areas of both the south and north of the country.

With the escalation of industrial production in the first decade of the 20th century, this migration would intensify. By the time of the commencement of World War I in Europe, immigration from the continent was curtailed and the labor shortage in the northern cities was filled by African American labor.

At the conclusion of the War, where the U.S. only entered after 1917, a series of so-called race riots would erupt in over 20 cities throughout the country. The most deadly of the riots would occur in Chicago during the summer months of 1919.

After 1910 thousands of African Americans began to stream into the city of Chicago facing fierce competition with white ethnic groups for jobs, housing and public accomodations. The neighborhoods and beaches were informally segregated and the death of an African American youth who was hit in the head with a rock and drown by a mob at the 29th Street beach in the Douglass community on the South Side, prompted widespread fighting.

Tensions flared and racial unrest ensued for over a week. White mobs attacked, beat and murdered African Americans resulting in the deaths 23 people. African Americans fought back and at least 15 whites were killed.

In the aftermath of the unrest the-then Illinois Attorney General Edward Brundage and State's Attorney Maclay Hoyne collected evidence for a grand jury investigation. On August 4, 1919, indictments were handed down against 17 African Americans, yet no whites were ever charged despite the gangs that roamed the black community attacking individuals, homes and businesses.

Although the racial unrest in Chicago would shock the United States and the world in the wake of World War I, it also illustrated the growing militantcy among the African American people. Many of the African American veterans who had returned from the war were not willing to accept the blatant racial discrimination they had endured for decades in the South after the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Prior to the U.S. intervention in World War I, African American scholar W.E.B. DuBois would publish an article entitled "The African Roots of War" which outlined the renewed attitude of resistance among the oppressed peoples of the world. In this article published in the Atlantic Monthly, DuBois states that "The Colored Peoples will not always submit passively to foreign domination. To some this is a lightly tossed truism. When a people deserve liberty, they fight for it and get it...Colored People are familar with this complacent judgement. They endure the contemptuous treatment meted out by whites to those not 'strong' enough to be free. These nations and races composing as they do a vast majority of humanity, are going to endure this treatment just as long as they must and not a moment longer." (Atlantic Monthly, 1915)

With the conclusion of World War I, the conditions were ripe for a major thrust towards Pan-Africanism on a global scale. DuBois set out to reconvene the Pan-African Congress in Paris, paralleling the peace conference that was occuring in France.

The presence of hundreds of thousands of Africans in the colonial armies who fought alongside the French and the Americans during the war, the consciousness and determination of these communities were heightened in regard to the desire for the abolition of colonialism and racism. When the Congress was held in February 1919, it enjoyed the participation of fifty-seven delegates from throughout the African world.

At this gathering some fifteen territories were represented including Abyssinia (Ethiopia), Haiti, the United States, the French-controlled Caribbean, the British-controlled colonies of West Africa, Egypt, the Congo, the Dominican Republic and Liberia. There were also representatives who attended from the European colonial powers as well as the United States, which was represented by William E. Walling and Charles Edward Russell.

In order to hold such a Congress in France at the pinnacle of the colonial era, DuBois was compelled to gain the permission of the authorities through the assistance of Blaise Diagne, who was a West African representative in the government of the colonial leader, Clemenceau.

According to DuBois "Diagne secured the consent of Clemenceau to our holding a Pan-African Congress, but we then encountered the opposition of most of the countries in the world to allowing delegates to attend. Few could come from Africa, passports were refused to American Negroes and English whites." (W.E.B. DuBois Reader, edited by Andrew G. Paschal, p. 242, 1971)

DuBois continues by pointing out that "The Congress therefore, which met in 1919, was confined to those representatives of African groups who happened to be stationed in Paris for various reasons. The Congress represented Africa partially. Of the fifty-seven delegates from fifteen countries, nine were from African countries with twelve delegates. Of the remaining delegates, sixteen were from the United States and twenty-one from the West Indies."

During this same period of the post World War I years, the charged racial tensions provided fertile ground for the emergence of the Garvey Movement initiated by the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Founded in 1914 in Jamaica, the UNIA relocated in the United States after Garvey immigrated to the country in 1916.

In the aftermath of the Red Summer of 1919 and the UNIA Convention in Montreal, the Garvey Movement would grow by leaps and bounds. At the 1919 Convention in Montreal the parents of Malcolm X would meet as leading activists within the UNIA. Louise Little was a writer for the Negro World newspaper founded by Garvey and circulated internationally.

Malcolm X, Egypt and the African Revolution

It was during the mid-1950s that Malcolm X Shabazz became a leading figure in the Nation of Islam and the African American community. Malcolm had been born into a Garveyite household in 1925 in Omaha, Nebraska.

According to Malcolm X in his autobiography, his father, Earl Little, a preacher and organizer for the UNIA, was killed by a white racist organization in Mason, Michigan in 1931. Malcolm's mother, left to raise seven children on her own, was ostracized by the white establishment in Michigan and was admitted to a mental institution.

The Little family was broken up and Malcolm was sent to live in foster homes until he was a teenager when he went to Boston to stay with an older sister fathered by Earl Little in a previous marriage. Malcolm would drift into petty crime and serve prison time between 1946 and 1952.

He would educate himself further within the prison system in Massachusetts and join the National of Islam along with several of his brothers. After leaving prison he became the national spokesperson for the Nation in 1957 and by 1959-60, he was widely recognized as a public speaker and media personality.

In 1956, during the Egyptian war to reclaim the Suez Canal from Britain and France, the Nation of Islam would take a position in support of the Nasser government. Malcolm traveled to Ghana and Egypt in 1959 as an emissary of Elijah Muhammad, the leader of the Nation of Islam.

Nonetheless by late 1963, Malcolm X would be silenced within the Nation of Islam and in March 1964, he left the organization to form the Muslim Mosque, Inc. and later the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU).

In April 1964, Malcolm would make hajj in Saudi Arabia and visit Egypt once again. He was warmly welcomed by the government of President Gamel Abdel Nasser, who had taken power in a revolutionary coup of mainly lower-ranking military officers later known as the Revolutionary Command Council.

Egypt at this time was a base of training and operations for national liberation movements in Africa and in the Arab world. Malcolm returned to New York in May of 1964 and would officially launch the OAAU on June 28 of that same year.

The organization was initially formed in Ghana in May during a visit by Malcolm. The OAAU was started by Malcolm with numerous African American expatriates living in Ghana, which at the time was known as the fountainhead of Pan-Africanism.

In New York at the founding OAAU meeting, Malcolm X said that "The Organization of Afro-American Unity shall include all people of African descent in the Western hemisphere, as well as our brothers and sisters on the African continent. Which means anyone of African descent, with African blood, can become a member of the Organization of Afro- American Unity, and also any one of our brothers and sisters from the African continent." (OAAU Founding Rally, June 28, 1964, Taken From "By Any Means Necessary," p. 40, 1970)

Malcolm X continued in this address saying "Because not only is it an organization of Afro-American unity in the sense that we want to unite all of our people in the West, but it's an organization of Afro-American unity in the sense that we want to unite all of our people who are in North America, South America, and Central America with our people on the African continent. We must unite together in order to go forward together. Africa will not go forward any faster than we will and we will not go forward any faster than Africa will. We have one destiny and we've had one past."

According to the book "By Any Means Necessary," a collection of the speeches of Malcolm X edited by George Breitman,"On July 5 he" (Malcolm) also noted at the second OAAU rally in New York that the Organization of African Unity (OAU), formed in May 1963, "was to meet in Cairo on July 17 and said 'We should be there letting them know that we're catching hell in America.'" (p. 108)

The book continues noting that "Malcolm left New York on July 9 and did not return until November 24. He spent most of the first half of this time in Cairo, and most of the second half visiting other countries in Africa." (p. 108)

Upon Malcolm X's (El Hajj Malik Shabazz) return to the African continent in July 1964, he attended the second summit of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) that was held in Cairo. At this gathering of African heads of state and liberation movements, Malcolm X sought to lobby on behalf of the OAAU and the African American people as a whole for the support of the struggle inside the United States.

During the summit in Cairo, Malcolm stated in an interview that "one of the main objectives of the OAAU is to join the civil rights struggle and lift it above civil rights to the level of human rights. As long as our people wage a struggle for freedom and label it civil rights, it means that we are under the domestic jurisdiction of Uncle Sam continually, and no outside nation can make any effort whatsoever to help us. As soon as we lift it above civil rights to the level of human rights, the problem becomes internationalized, all of those who belong to the United Nations automatically can take sides with us in condemning, at least charging, Uncle Sam with violation of our human rights." (Interview with Milton Henry of the Afro-American Broadcasting Corporation in Cairo)

In a letter by Malcolm X from Cairo written on August 29, 1964, he states that "My stay here in Egypt is just about drawing to a close; my mission here in your behalf is just about complete in this part of Africa. For the next few weeks, unless something drastic happens to force me to change my plans, I will be traveling through several other African countries visiting and speaking in person to various African leaders at all levels of government and society, giving them firsthand knowledge and understanding of our problems, so that all of them will see, without reservation, the necessity of bringing our problem before the United Nations this year, and why we must have their support." (By Any Means Necessary, p. 110)

Malcolm in this same letter from Cairo asserts the fact that "You must realize that what I am trying to do is very dangerous, because it is a direct threat to the entire international system of racist exploitation. It is a threat to discrimination in all its international forms. Therefore, if I die or am killed before making it back to the States, you can rest assured that what I've already set in motion will never be stopped."

The letter goes on to point out that "The foundation has been laid and no one can hardly undo it. Our problem has been internationalized. The results of what I am doing will materialize in the future and then all of you will be able to see why it is necessary for me to be here this long and what I was laying the foundation for while here."

Malcolm X upon his return to the United States in late November 1964 would speak out more forcefully than ever against U.S. imperialism and its efforts to stifle the African liberation struggles on the continent. At the homecoming rally of the OAAU on November 29, 1964, he pointed out that the "thing that I would like to impress upon every Afro-American leader is that there is no kind of action in this country ever going to bear fruit unless that action is tied in with the overall international struggle." (p. 153)

Conclusion

The escalating struggle against the world economic crisis and the unresolved questions of genuine national independence, unity and socialism, are converging today for a new generation of organizers to address. Africans and oppressed people in the United States must learn the lessons of the movements of the 20th century in order to adequately prepare for the task ahead in the coming years and decades.

With the uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt in North Africa, along with the burgeoning struggles in Yemen, Bahrain, Jordan and Djibouti, the central role of the working class, the youth, women and farmers must remain paramount in order for these movements to bring about a genuine change and transformation of the neo-colonial states. The first phase of the movements in Tunisia and Egypt have been successful in mobilizing millions in the effort to remove a dictatorial leader supported and promoted by western imperialism.

Nonetheless, the ultimate aim of the people's struggle must be designed to fundamentally transform society as a whole. The ravages of capitalism and imperialism must become the focus of the workers and the youth because their aspirations cannot be met under the existing economic system of exploitation and oppression.

Africans, the oppressed and working people in general must pledge their unconditional support to all of the legitimate struggles taking place in the world to end racism, capitalism, imperialism and all other forms of reaction and backwardness. It is the escalating solidarity of the workers and oppressed of the world that will secure a future devoid of exploitation and inequality.

1 comment:

Excellent post, comrade Abayomi! Raleigh FIST just did a study on the people's movements in North Africa and we used this piece as one of the readings. The intersections of the struggles that you highlight in this article are very important. We know from our struggle here inside the US, that, as Malcolm X said, the struggle must become international. This means that the struggle must also organize the unorganized, especially the US South where the majority of Black people live. When you mentioned the 1934 strikes you didn't mention the important role that the textile strike played in that, this wasn't secondary to the San Francisco and Minneapolis strike. The strike in Gastonia Loray Mills was very significant and failed to get support by leftists and revolutionaries around the country that it needed to sustain and continue to build a genuine labor movement in the South. We must do everything we can to correct these historical errors and organize the South!

Post a Comment