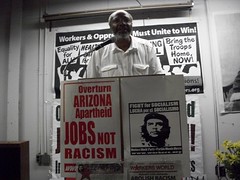

Abayomi Azikiwe, editor of the Pan-African News Wire, addressing a public forum honoring Black August. The event was held on August 7, 2010. (Photo: Andrea Egypt)

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire File Photos

Assessing his contributions amid uprisings in North Africa and ongoing national oppression in the Diaspora

By Abayomi Azikiwe

Editor, Pan-African News Wire

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the death of Frantz Fanon, a revolutionary thinker and practitioner who has had a tremendous impact politically on the African liberation struggle both on the continent and in the Diaspora. The recent outbreaks of strikes, mass protests and rebellions in Tunisia, Algeria and Egypt requires a reassessment of the significance of the events that Fanon participated in during his lifetime as well as the views expressed through a series of articles and books published in the 1950s and early 1960s.

Fanon’s views on the nature of the psychology of the oppressed, which he studied systematically in France and in North Africa, his analysis of social class formations in colonial societies, attempting to gage the response of these classes to the developing revolutionary struggle against imperialism and for the construction of a socialist society, and his impact on continuing political movements that have arose since his death, such as the African American movement of the 1960s and 1970s, should be extended into the current period in examining the U.S. occupation of Iraq and Afghanistan, the political upheavals in North Africa related to the influence and presence of United States military forces in the region, as well as the escalating struggles of Africans in the Diaspora, who are battling daily against intensified oppression, exploitation and racism.

Before we can make the case for not only a re-examination of Fanon’s works, but a broadening of his influence within the African world community, we have to look at both the political context under which Fanon produced his most significant theoretical formulations and how this context represents a continuation of struggles against U.S. and European imperialist domination in North Africa and the Arab Peninsula.

Also we must examine the extension of that same struggle of fifty years ago to events taking place today on a global level. Even though the form of struggle has changed, the underlying causes for the intensification of military interventions by western imperialism, is clearly an effort to re-gain the perceived losses of the anti-colonial period beginning with the close of World War II.

Fanon’s Time in History

Born in the Caribbean island of Martinique in 1925, Fanon was a social product of French colonialism. During the post-World War I period there was a monumental upsurge in political violence throughout the colonized world. In the Caribbean and the United States, the influence of Marcus Garvey was paramount.

African Americans also began to produce an abundance of cultural materials, which together with Garveyism, spread its influence in colonial territories on the African continent and in the Caribbean. In addition, the impact of the Bolshevik revolution in Russia, which triumphed in 1917, had a tremendous impact on the rise of anti-capitalist sentiments among oppressed and working people worldwide.

Fanon, who had trained in France as a psychiatrist, was later assigned to work as a functionary of the colonial regime in Algeria, which the French had occupied since 1830. As an oppressed African born in another French dominated territory in the Caribbean, Fanon began to identify with the Algerian masses in their struggle against colonialism.

Utilizing his observations of the situation involving the liberation of Algeria, Fanon began to develop specific theoretical ideas related to the nature of an anti-colonial struggle during this period. He later participated in the 1956 Black Writer’s Conference in Paris which examined the notion of cultural continuity between African peoples internationally. Even during this early period of his development, Fanon’s ideas were running far ahead of his literary and philosophical contemporaries.

In December of 1958 he attended the historic All-African People’s Conference in Accra, Ghana, which was convened by the then Prime Minister and leader of the ruling Convention People’s Party, Dr. Kwame Nkrumah. After this conference, which enjoyed the participation of 62 anti-colonial organizations, Fanon was later invited to relocate in Accra as a permanent representative for the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN). It was his experiences in Ghana as well as Tunisia during this time that shaped his observations related to the post-colonial period.

Fanon saw the ideological and political bankruptcy of the post-colonial ruling elite who constituted the dominant social class within many of the nationalist parties which led the fight for independence. According to Fanon’s observations, this elite cannot fulfill its historic role of transforming itself from a petit-bourgeois strata to a full-blown national bourgeoisie in the western industrial sense of the term.

A strata such as the petit-bourgeoisie of Africa, can only imitate in a vulgar fashion the attributes of the former colonial rulers. Without an objective class basis for the acquisition of capital, the new post-colonial elite became the automatic junior partners of the international bourgeoisie.

In the "Wretched of the Earth" Fanon says that “The national middle class which takes over power at the end of the colonial regime is an underdeveloped middle class. It has practically no economic power, and in any case it is no way commensurate with the bourgeoisie of the mother country which it hopes to replace.”

Fanon continues by pointing out that “In its narcissism, the national middle class is easily convinced that it can advantageously replace the middle class of the mother country. But that same independence which literally drives it into a corner will give rise within its ranks to catastrophic reactions, and will oblige it to send out frenzied appeals for help to the former mother country.”

This is the crisis of leadership, organization and ideology facing the peoples of the Third World. At the mass base this phenomena of political marginality is manifested in the socio-psychological alienation of the popular classes. It is among this section of the overwhelming majority of the people that Fanon places his hopes for revolutionary transformation.

In Fanon’s estimate the only salvation for the national bourgeoisie in the Third World is to abandon its own ostensible class interests and move to integrate completely with the mass struggles aimed at the abolition of the colonial legacy. This failure to assimilate western values by the popular classes of workers and peasants has created mental disorders peculiar to the colonized masses, which Fanon has written on extensively.

Beyond Alienation to Self-Emancipation

By transcending the subjective state that the colonial powers had placed the oppressed, this became the focal point in arousing mass consciousness for social transformation. According to Renate Zahar “In the same measure as the individual’s contact with the colonial power and its institutions grow closer, he (and she) increasingly undergoes processes of alienation. He (and she) becomes more and more uncertain with regard to the conduct he should adopt. His (and her) potential of revolutionary resistance decreases proportionately, since his acceptance of the colonialist ideology prevents him from realizing the causes of alienation.” (Zahar, Frantz Fanon: Colonialism & Alientation, Monthly Review, 1974)

In order for the process of liberation to begin, there must be an understanding by the oppressed that their existence can no longer remain static and that the possibility of change, although its consequences can be quite violent, is a much brighter prospect than remaining in the oppressed state.

This is the attitude that permeates the masses in the early stages of revolt. It is the underlying basis of the level of consciousness rising among those who are engaged in broad ranging industrial action or armed revolutionary struggle.

Even after the attainment of national independence, the potential for perpetual rebellion still exist if the governing regime has not moved to re-correct the exploitative conditions which were characteristic of colonial society.

Fanon in "The Wretched of the Earth" states that the decolonization process is inherently violent: “It transforms spectators crushed with their inessentiality into privileged actors, with the grandiose glare of history’s floodlights upon them. It brings a natural rhythm into existence, introduced by new men (and women), and with it a new language and a new humanity.”

Therefore, the socio-psychological alienation of the oppressed masses can only be effectively treated and cured within the context of the revolutionary national liberation movement, which undertakes the struggle against injustice, exploitation and oppression, for the creation of a genuinely equal and democratic society.

Fanon’s Legacy in Our Time

Many people may be tempted to make the argument that Fanon’s theory of the redemptive nature of revolutionary violence by the oppressed against colonial and neo-colonial domination would not be applicable in analyzing the current struggles raging throughout North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Yet despite the contradictions which have arisen within the post-colonial states and societies over the last five decades, there is still a continuing desire among the workers and the oppressed for genuine emancipation, unity and socialism.

With specific reference to the United States, the ideas of Frantz Fanon played an instrumental role in revolutionizing the civil rights and black power movements of the 1960s. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) would study Fanon and his influence was also profound within the Black Panther Party.

James Forman, the former executive secretary and international affairs director of SNCC wrote in his political autobiography that “There was no real division between the sugar cane fields of Martinique and the cotton fields of the American South, between the French racists and the American ones, between the mental colonization that Fanon fought and the psychological oppression of young black Sammy Younge,” a civil rights student activist killed in Alabama in January 1966. (Forman, The Making of Black Revolutionaries, p. 550)

Although it is not clear which direction these movements will take as the struggles unfold, it is obvious that the impact of this crisis for U.S. imperialism can potentially change the political character of the North Africa and Arab Peninsula regions. Such a loss of influence within the region could fuel the working class and national struggles inside the confines of the United States where the exploitation and oppression of the people has intensified with the advent of the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression.

There are various political and social currents involved in this historical conjuncture: the struggle for Palestinian self-determination and nationhood; the necessity for a democratic revolution throughout the feudal monarchies of the area, particularly within the Gulf states; and the rising tide of revolutionary Islamic and left tendencies, which causes the most consternation among the imperialist states.

None of these struggles in the North Africa and Arabian Peninsula regions can reach fruition without a fundamental challenge to transform the leading imperialist country in the world, the United States. All of these political and social tendencies are arising from a desire among the masses within the various regions of the world to defeat imperialist influence and domination of their countries.

Fanon’s significance to this current situation as well as the relevance of other African revolutionary thinkers and practitioners of the modern period, is that these developments provide the working class and the oppressed with profound lessons and guides to action aimed at self-emancipation and the construction of truly revolutionary societies.

In light of the economic crisis of imperialism, what does the workers and oppressed of the world have to lose? They stand to relinquish their existing ruling classes and to gain a world devoid of the exploitation of human beings by other human beings.

No comments:

Post a Comment