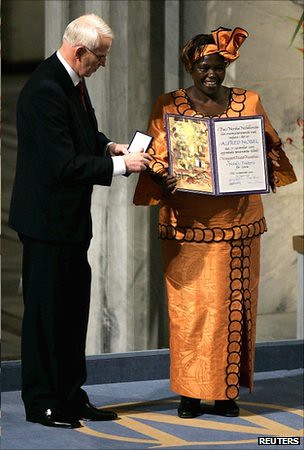

Dr. Wangari Maathai of Kenya winning the Nobel Prize. She recently passed away after a long battle with cancer. Her work centered around environmental issues in Africa., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

Wangari Maathai: Death of a visionary

Wangari Maathai's compelling life story is inextricably linked with the social and political changes that so much of Africa has been through since the idea of throwing off European colonialism began to gain traction shortly after World War II.

Her unique insight was that the lives of Kenyans - and, by extension, of people in many other developing countries - would be made better if economic and social progress went hand in hand with environmental protection.

The Green Belt Movement, which she founded in 1977, has planted an estimated 45 million trees around Kenya.

The straightforward environmental benefits of that would have been important enough on their own in a country whose population has grown more than 10-fold over the last century, creating huge pressure on land and water.

But what made the movement more remarkable was that it was also conceived as a source of employment in rural areas, and a way to give new skills to women who regularly came second to men in terms of power, education, nutrition and much else.

Now, she has succumbed to a battle with cancer. But if cancer was new to her, battle was definitely not; it was a way of life.

Opposing a major government-backed development in Nairobi, she was labelled a "crazy woman"; it was suggested that she should behave like a good African woman and do as she was told.

Her former husband made similar comments when suing for divorce: she was strong-willed, and could not be controlled.

This alone gives some idea of the battles Dr Maathai fought in the politically active phase of her life, which encompassed and indeed wove together the ideals of helping Kenya develop sustainably and helping Kenyan women achieve equality.

But without the progress of post-colonial reforms, it's doubtful that she would have been able to achieve a fraction of what she did; the times she lived in generated the tides she fought against, but they also provided the means with which to fight.

Dr Maathai highlighted the damage that illegal logging was doing to forests and livelihoods Post-colonial links with the West offered Africans of great intellect but poor background the chance to study abroad, in the US and Germany.

This brought her the knowledge of biology and the PhD that both opened doors in corridors of influence and gave scientific underpinning to the environmental restoration work on which she embarked.

Another vital strand in her life was the creation of global environmental organisations, in particular the United Nations Environment Programme (Unep) in 1972.

These organisations desperately needed to tap into expertise in the developing world, especially because it was in these countries that the vicious circle of environmental degradation, unsustainable population growth and poverty was at its most grinding.

With its headquarters situated in the Kenyan capital Nairobi, Wangari Maathai was one of the first people from the developing world adopted into the Unep "family", which meant global exposure and, relatively, a huge influence.

Among other things, that meant the capacity to spread the Green Belt philosophy to other countries where the ecological and economic need is even more pressing than in Kenya - notably the Congo Basin, where warring factions and deep poverty have put huge pressure on forests and the wildlife they maintain.

Eventually, this would all lead to the award in 2004 of the Nobel Peace Prize - the first time it had gone to an African woman, and arguably the first "green Nobel".

Tourists flock to Lake Nakuru's flamingos - an example of environmental protection bringing revenue I say "arguably" partly because previous prize-winning work had contained an environmental component, such as that of Paul Crutzen, Sherwood Rowland and Mario Molina who deciphered the chemistry of ozone depletion.

And partly because the citation itself does not explicitly mention the word "environment", reading: "for her contribution to sustainable development, democracy and peace".

In other words, it's not just planting trees - it's the reasons why trees are planted, it's the social side of how the tree-planting works, it's the political work that goes alongside tree-planting, and it's the vision that sees loss of forest as translating into loss of prospects for people down the track.

There is, in some parts of the world, a backlash now against these ideas.

Every couple of days an email comes into my inbox asserting that the way to help poorer countries develop is to get them to exploit their natural resources as quickly and deeply as possible with no regard for problems that may cause.

Organisations promoting this viewpoint are not, to my knowledge, based in the developing world but in the Western capitals that might make use of the fruits of such exploitation - cheaper wood, cheaper oil, cheaper metals.

It is the opposite of sustainable.

But the existence of these lobby groups can be seen as a testament to the influence that Wangari Maathai and others like her have had on global debate.

The UN initiative on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (Redd), the linking of biodiversity to livelihoods, moves to strengthen the rule of law as a pre-requisite for environmental health, and the notion that communities should gain when the natural resources they maintain are exploited - all these in part trace their roots back to Wangari Maathai and the Green Belt Movement.

A Facebook page for tributes is laden with short but moving comments that in a way sum up everything she was and achieved.

"If all us who loved her will plant a tree on her hon: she will smile from the windows of heaven seeing green world. I will plant one today".

"You have been a true inspiration to those who love and care for nature".

And perhaps the most moving of all: "You made a difference".

No comments:

Post a Comment