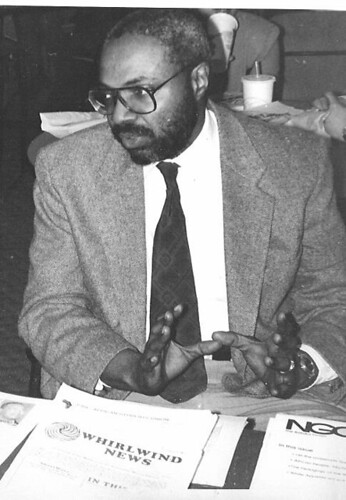

Abayomi Azikiwe as director of the Pan-African Research & Documentation Center in Detroit. In 1998 he formed the Pan-African News Wire. The news agency has published thousands of articles in over 100 different publications and websites., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

Great-Granddaughter of Ida B. Wells-Barnett Seeking Monument to Anti-Lynching Crusader

Pioneer in civil rights, women’s emancipation and social welfare deserves tribute in Chicago

By Abayomi Azikiwe

Editor, Pan-African News Wire

150 years ago on July 16, 1862, Ida B. Wells-Barnett was born into the antebellum slave system in Holly Springs, Mississippi. Wells-Barnett, who died on March 25, 1931 during the Great Depression, is still recognized today as one of the early pioneers in the struggle against lynching and for the rights of African Americans, women and the working poor.

During late 2011, an effort was undertaken by the great-granddaughter of Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Michelle Duster, to have a sculpture placed in the location where a housing project named after the anti-lynching activist once stood on Chicago’s south side. The Ida B. Wells Homes opened in 1941 and was part of the New Deal era Public Works Administration construction projects.

The Wells Homes suffered the same fate as other public housing projects in Chicago and throughout the United States. In the decades after World War II when larger numbers of African Americans migrated from the southern states to the northern industrial regions, racist employment and residential practices led to the systematic segregation of urban areas in the country.

This de jure and de facto segregation stemmed from the conscious policies of the ruling class in the U.S. to divide the working class in order to continue the super-exploitation of the African American population. Housing projects, although considered progressive for providing low-income residents when they were first built during the mid-20th century, later became the dumping-grounds for African Americans.

The Wells Homes, which consisted of 1,662 units with more than 860 apartments and nearly 800 row houses, deteriorated over the decades. By the 1990s, the area became a center for drug activity and gang-related crime and violence.

In an article published by the Associated Press it noted that “In an infamous 1994 case, two boys, ages 10 and 11, dropped a 5-year-old boy to his death from a vacant 14-floor apartment. The boys were convicted on juvenile murder charges.” (Associated Press, December 30, 2011)

This case gained nationwide attention and illustrated the conditions under which millions of African Americans lived in urban areas. The Associated Press recalled in the same article that “The same year two neighborhood teenagers produced an award-winning radio documentary ‘Ghetto-Life 101,’ which aired on National Public Radio.”

Eventually by 2002, the final buildings at the Wells Homes were torn down. Other housing projects in Chicago such as the Robert Taylor Homes and Cabrini Green would also be razed in a federal and local government program purportedly aimed at eliminating blight and encouraging more humane living conditions for low-income city dwellers.

Nonetheless, the government policies of eliminating public housing and refusing to invest adequate sums of public money into building low and moderate-income communities contributed significantly to the burgeoning problem of homelessness as well as foreclosures and evictions. Today the lack of quality and affordable housing is one the most serious problems facing working people under capitalism.

The Legacy of Ida B. Wells-Barnett

It was not until the emergence of the campaign launched by Ida B. Wells during the early 1890s that there was widespread attention given to the genocidal wave of terror inflicted on African Americans centered in the southern United States, but not necessarily limited to this region. Wells, whose parents had been enslaved, studied at Shaw University and eventually became a primary school teacher in Mississippi as well as in Shelby County, Tennessee.

Her parents died in the yellow fever epidemic of the late 1870s that struck Mississippi and southwest Tennessee. Soon Wells went to Memphis to live with the widow of her uncle who had also perished during the yellow fever epidemic.

It was during her tenure as a school teacher in Woodstock, Tennessee in 1884 that she became embroiled in a racial segregation lawsuit after the young educator was forcibly removed from a ladies’ coach reserved for whites-only on the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad. After filing suit in the Circuit Court and winning a favorable judgment against the railroad company, the firm appealed to the State Supreme Court of Tennessee, having the lower court’s decision overturned against Wells.

As a young school teacher in Memphis, Wells participated in the social life of the African American community during this period. She joined a lyceum in the city where she read poetry, essays and engaged in debates on the contemporary issues of the times. After making an impression on her colleagues at the lyceum, she was asked to take over the editorship of their literary journal, the Evening Star.

Later she would take partial control of the Free Speech and Headlight newspaper in Memphis. This was a period of flowering for numerous African American newspapers which covered issues the white-dominated corporate publications would never address.

Eventually she would take full control of the newspaper then called the Free Speech. It was during the course of building her reputation as a newspaper publisher and editor that a murderous act of mob violence in Memphis would change the course of the life of Ida B. Wells. While away from Memphis on newspaper business in Natchez, Mississippi, word came to Wells on the lynching of Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell and Henry Stewart who were friends of the Free Speech editor.

According to published newspaper reports of the period, the three African American men had wounded three whites who had unlawfully entered a store they owned in order to carry out a robbery. The three Black men were arrested and placed in the Shelby County jail where some days later a select group of whites were admitted by the authorities inside the lock-up in order to remove Moss, McDowell and Stewart.

The men were forced on to a switch engine rail car which ran in back of the county jail. The three were taken one mile north of Memphis city limits and shot to death by the white mob.

Wells was outraged by the killings and wrote fiery editorials denouncing the authorities in Memphis for allowing such actions to take place without any attempts at prosecuting the perpetrators. While away on a speaking tour the offices of the Free Speech were ransacked and destroyed.

Wells wrote in her autobiography that “I had bought a pistol the first thing after Tom Moss was lynched, because I expected some cowardly retaliation from the lynchers. I felt that one had better die fighting against injustice than to die like a dog or a rat in a trap.” (Wells-Barnett, Crusade for Justice, p. 62)

Wells never returned to Memphis to live after the destruction of her newspaper offices. She would travel throughout England, Scotland and Wales in 1893-94 speaking on the atrocities being committed against African Americans in the U.S. She would continue as a newspaper writer and public lecturer for the remaining years of her life.

In 1895 she would publish the first serious study on the problem of racially-motivated mob violence. This book was entitled: “A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynchings in the United States, 1892-1893-1894.”

Wells would marry Attorney Ferdinand Lee Barnett in 1895, the founder of the Conservator, the first African American newspaper in Chicago. She was an early proponent of women’s suffrage and in Chicago, where she re-located to live the remainder of her life, she worked as a leader in the African American women’s club movement, the Equal Rights League and the Negro Fellowship League.

Monument Commissioned in Chicago

The Ida B. Wells Commemorative Committee is attempting to raise $300,000 in donations to complete the project. Chicago artist Richard Hunt has been commissioned to create the sculpture, which will combine an image of Wells along with her writings.

Michelle Duster said of the project that “I want people to remember Ida B. Wells the woman, not Ida B. Wells the housing community. Something should be done to remember who she was.” (Associated Press, December 30, 2011)

Duster went on to comment that “I think who she was as a woman got lost when it was attached to the housing projects. Her name and what she did can’t be lost with the housing project.”

No comments:

Post a Comment