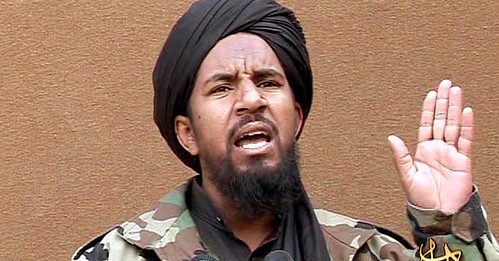

Abu Yahya al-Libi was reportedly killed by a United States drone attack in Pakistan. Thousands have been killed by these attacks over the last few years., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

Drone Strike That Kills Al-Qaeda Leader Leaves Questions

By John Walcott and Tony Capaccio

June 05, 2012

The U.S. drone that spotted al- Qaeda’s second-in-command getting into a car, followed him to a house in a North Waziristan tribal region and killed him on June 4 dealt another serious blow to the terrorist group’s remaining core in Pakistan, administration officials said.

Even with the success of an attack that the officials said was approved by President Barack Obama, the dearth of actionable real-time intelligence on alleged terrorists remains a weak link in the administration’s intensified campaign of almost 300 drone strikes in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Yemen and Somalia.

Eleven years after the attacks of September 11, the U.S. still has little human intelligence of its own from terrorist sanctuaries in northwestern Pakistan and only sporadic and selective intelligence from Afghan and Pakistani liaison officers, the officials said -- which helps explain why it took more than 24 hours to confirm that Abu Yahya al-Libi was dead.

“Intelligence is never going to be 100 percent accurate,” said Rick “Ozzie” Nelson, director of the Homeland Security and Counterterrorism Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington. “The president himself has to decide how much risk he’s willing to take when he approves a strike. You have to consider the possible benefits -- the value of a target -- against the risk.”

Confirming Death

Confirming the death of someone such as al-Libi can be as difficult as locating the terrorist in the first place, the officials said. Mobile-phone calls, text messages, e-mails and jihadist social media and websites are unreliable and sometimes used to provide false information, they said, noting false reports of al-Libi’s death after a December 2009 drone strike.

Missile attacks can make photo recognition difficult, said the officials, who declined to discuss how or in what condition al-Libi was identified, except to note that he had previously been in U.S. custody.

The Predator drone’s video camera and sensors spotted al- Libi getting into his car, and then followed the vehicle to the house, two U.S. officials said. While Pakistani sources reported that the subsequent attack had killed his driver and bodyguard, there was no confirmation of al-Libi’s death until yesterday, according to the officials, who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss a covert operation.

White House spokesman Jay Carney told reporters yesterday that al-Libi served as al-Qaeda’s “general manager,” overseeing day-to-day operations in the tribal areas of Pakistan and working with al-Qaeda’s regional affiliates.

“There is now no clear successor to take on the breadth of his responsibilities,” Carney said. “This would be a major blow, we believe, to core al-Qaeda, removing the No. 2 leader for the second time in less than a year and further damaging the group’s morale” and “bringing it closer to its ultimate demise than ever before.”

Al-Libi’s Stature

Al-Libi, arrested in Pakistan in 2002, was among the prisoners who escaped from the U.S.-run prison at Bagram air base in Afghanistan three years later, which boosted his standing among militants. He took over as the core al-Qaeda group’s No. 2 after U.S. raiders killed Osama bin Laden at a hideout in Pakistan 13 months ago and Egyptian Ayman al-Zawahiri moved up to the top position.

U.S. attacks have killed more than a dozen al-Qaeda commanders in Pakistan since bin Laden’s death. That has left fewer than half of the group’s 32 identified leaders -- and only Zawahiri and one other key figure, Kuwaiti Sulaiman Abu Ghaith - - believed alive, the two U.S. officials said. The available intelligence suggests that the group’s dwindling core in Pakistan has been unable to find equally experienced replacements, they said.

Limited Intelligence

In al-Libi’s case, targeting the Libyan in the Pakistani village of Khassu Khel was worth the risk of missing him, perhaps killing innocent people, and further damaging the frayed U.S. relationship with Pakistan, which condemned the strike, the two U.S. officials said.

Al-Libi was among al-Qaeda’s most experienced and versatile leaders –- an operational trainer and the head of the Central Shura, or ruling council –- and he played a critical role in the group’s planning against the West, according to a third U.S. official.

In addition to his standing as a longtime member of al- Qaeda’s leadership, al-Libi’s religious credentials gave him the authority to issue fatwas, or religious orders, to approve terrorist operations, and to provide guidance to al-Qaeda’s core in Pakistan and to its regional affiliates, according to the third official, who also spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss an intelligence operation.

Chemistry Student

Al-Libi, an English-speaking Libyan whom U.S. intelligence officials think was born about 1963 and studied chemistry in Libya, appeared often in al-Qaeda videos. He was described on a U.S. State Department website as “a key motivator in the global jihadi movement, and his messages convey a clear threat to U.S. persons or property worldwide.”

The department listed him as one of America’s most wanted terrorists, and in one announcement for its Rewards for Justice program offered $1 million for information leading to his capture. Al-Libi, it said, used his Sunni Muslim “religious training to influence people and legitimize the actions of al- Qaeda.”

Jarret Brachman, a terrorism expert at Cronus Global, LLC, a security consulting firm, called al-Libi “media-savvy, ideologically extreme, and masterful at justifying savage acts of terrorism with esoteric religious arguments” in a September 10, 2009, article in Foreign Policy magazine.

Continuing Threat

Even so, the first two U.S. officials said, his death is unlikely to end the threat posed by al-Qaeda, especially considering that the group’s regional affiliates and allies in Yemen, Iraq, Somalia, Nigeria, Mali and elsewhere in North Africa are increasingly self-reliant and independent.

What’s more, they said, most of the intelligence on which the stepped-up drone attacks are based is imperfect at best, so they risk killing innocent people, fueling anti-American sentiment, and even recruiting more terrorists -- though less experienced ones -- than they kill.

In Yemen, for example, a Bloomberg reporter found that the drone strikes have provoked diverse reactions.

“These strikes are not acceptable, and we should not take the help of infidels to kill Muslims,” said Mohammed Hamud, a clothes peddler on Jamal Street in Sanaa, the capital. “Al- Qaeda might be just an excuse to interfere in our internal affairs,” he said loudly and angrily.

Spawning Militants?

Drone strikes won’t uproot al-Qaeda militants, but will increase their number, said Mohammed al-Sabri, a leader of the Joint Meeting Parties, an opposition coalition that’s taking more than 50 percent of the seats in a new unity government, in a May 17 telephone phone interview.

“What we need is to fill up the swamp with earth rather than fight the mosquitoes,” al-Sabri said.

Other Yemenis supported the drone strikes in their country. Taha Yassin, 21, a student at Sanaa University, said he isn’t disturbed that an American sitting at a computer console is firing missiles at al-Qaeda.

“The recent U.S. drone strikes have been successful, and I think we need them to crack down on this terrorist organization,” Yassin said.

At the outset of the Iraq war, said Nelson at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, the U.S. Air Force used computer algorithms to help calculate the timing and targeting of manned air strikes to maximize their effect and minimize collateral damage and civilian casualties.

‘No Right Answer’

Now, said Nelson, “we’ve never conducted operations like this. At the end of the day, there’s no right answer to this. There’s no way to quantify the risks and benefits, no good metrics, and there’s no perfect intelligence, so there’s always going to be a degree of uncertainty.”

With last month’s report in the New York Times that Obama oversees the preparation of the top-secret process his administration uses to designate suspected terrorists for death or arrest, calculating the risks and benefits -- and living with the consequence of miscalculations -- falls to the commander-in- chief, said Nelson.

To contact the reporters on this story: John Walcott in Washington at jwalcott9@bloomberg.net; Tony Capaccio in Washington at acapaccio@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: John Walcott at jwalcott9@bloomberg.net

No comments:

Post a Comment