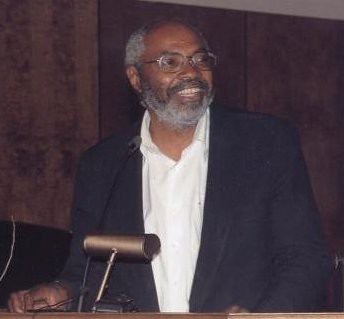

Abayomi Azikiwe, editor of the Pan-African News Wire, at New Bethel Baptist Church in Detroit on March 27, 2010. The event was a rally to demand justice in the assassination of Imam Luqman Ameen Abdullah by the FBI on Oct. 28, 2009., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

Nkrumah’s Literacy Contributions: Propagandist for Pan-Africanism and Socialist Revolution

From the United States, Britain and back to Africa the Osagyfo has continuing resonance

By Abayomi Azikiwe

Editor, Pan-African News Wire

Note: The following are excerpts from a presentation delivered in a class for the Marxist School of Theory and Struggle in New York City on June 16, 2012. The class was entitled Revolutionary Voices From the Oppressed World. The class was taught by Abayomi Azikiwe, editor of the Pan-African News Wire and Deirdre Griswold, the editor of Workers World newspaper.

Azikiwe examined the political legacy of Ghana through the work of Kwame Nkrumah and Griswold discussed the impact and contributions of the Ethiopian Revolution and its leader Mengistu Haile Mariam.

Deirdre Griswold was an eyewitness to developments in Ethiopia during the 1970s. She traveled as a journalist to Ethiopia and later produced two pamphlets: The Ethiopian Revolution and the Struggle Against U.S. Imperialism (June 1978) and Eyewitness Ethiopia: The Continuing Revolution (July 1978). Abayomi Azikiwe has traveled extensively on the African continent and is well known for publications on the history and political economy of the continent.

----------------------------------------------------

Kwame Nkrumah was a tireless organizer for the African Revolution that swept the continent and the Diaspora between the post-World War II period through the 1970s. A major source for the spreading of his ideas was directly related to his literacy influence.

Going back at least to his student days in the U.S., Nkrumah wrote for several publications and lectured broadly within the African student and the broader African American community. Nkrumah was a co-founder of the African Students Association (ASA) in the U.S. and reportedly worked with other organizations including Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and the Council on African Affairs (CAA) which was led by Dr. W.E.B. DuBois, Dr. Alphaeus Hunton and Paul Robeson.

Nkrumah’s date of birth is said to have been on September 21, 1909. He was born in Nzima located in southwest Ghana. His home village was Nkroful.

He was raised traditionally as well as within the Roman Catholic Church. Nkrumah attended Catholic schools and would later become a teacher. In later years he would assist in the formation of a teachers association to improve conditions and handle grievances.

His earliest nationalist sentiments were kindled through Dr. Kwegyir Aggrey, an educator who had attended university in the U.S. After hearing Aggrey at the Accra Teacher’s Training College, Nkrumah decided to seek higher education in the U.S.

Nkrumah assisted in the formation of the Nzima Literature Society and became more politically conscious. In his autobiography he wrote that “It was through this work that I met Mr. S.R. Wood who was then secretary of the National Congress of British West Africa. This rare character first introduced me to politics. He knew more about Gold Coast political history than any other person I have ever met and we had many long conversations together.”

Wood wrote Nkrumah a testimonial which assisted him in getting admitted to Lincoln University in 1935. Nkrumah was influenced by the nationalist newspaper the “African Morning Post” edited by Nnamdi Azikiwe of Nigeria and I.T.A. Wallace Johnson of Sierra Leone.

Azikiwe had studied in the U.S. at Howard University and upon returning to Africa set up his newspaper in the Gold Coast. When Abyssinia (Ethiopia) was invaded by the Italians in 1935, the African Morning Post was shut down and both Wallace and Azikiwe were deported from the Gold Coast.

Nkrumah set sail for the U.S. in 1935 after borrowing money for his passage through a relative living in Lagos, Nigeria. He arrived at Lincoln University almost penniless and worked his way through school attaining four degrees over the next decade.

Lincoln was the first institution of higher education designed for Africans. The school was formed in 1854 by Presbyterians.

At Lincoln University Nkrumah was active with the ASA and established along with Ako Adjei and Jones Quartey, the “African Interpreter” newsletter for the organization. He would also publish a series of articles on Black history in the campus newspaper.

Nkrumah obtained both bachelors and masters degrees from Lincoln and the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. While in the U.S. Nkrumah lived and worked among African Americans and took a keen interest in their social plight.

His academic qualifications were within the fields of economics, sociology, philosophy and theology. He would be certified as a theologian and travel extensively giving sermons and lectures in African American churches.

He would also debate E. Franklin Frazier, the African American sociologist, with whom Nkrumah disagreed over the retention of African cultural traits in the U.S. Nkrumah believed that African Americans were still very much connected with their ancestral traditions despite the experience of slavery in the U.S.

Two research articles written by Nkrumah were published in the University of Pennsylvania’s “Educational Outlook” journal. The first article that came to this writer’s attention was entitled “Primitive Education in West Africa,” which was published in the January 1941 edition.

Nkrumah begins this article citing Professor Arthur J. Jones’ “Principles of Guidance,” noting that education “is to prepare the individual for efficient participation in the activities of life. In other words, education should lead the individual into the highest, fullest, and most fruitful relationship with the culture and ideals of the society in which he finds himself, thereby fitting him for the struggle of life.” (Educational Outlook, Volume XV, Number 2, Francis N. Nkrumah, 87)

Another article published in the November 1943 edition of Educational Outlook takes on a much more political character. The article is entitled “Education and Nationalism in Africa.”

Nkrumah states in this article that “Human history has been dominated by two things: the quest for bread and the quest for human rights. Today we hear the deep strong voice of Africa in this quest for human rights.” (Educational Outlook, Volume XVIII, Number 1, Francis Nwia-Kofi Nkrumah, p. 32)

Towards the end of the article Nkrumah reveals his anti-imperialist consciousness by stressing that “Many of us fail to understand that a war cannot be waged for democracy which has as its goal a return to imperialism. It is our warning, that if after victory, imperialism and colonialism should be restored, we will be sowing the seed not only for another war, but for the greatest revolution the world has ever seen.” (p. 39)

The article continues this militant tone saying “Future wars will not be stopped by willful thinking, writing and talking, while at the same time conditions are being created which make freedom a mockery. Adequate organization to make all peoples free, adequate organization to stop fascism, imperialism, and all other forces of exploitation is the only effective desideratum to ensure world peace.” (p. 40)

World War II ended in Europe in May 1945 and Asia during August of the same year. Nkrumah re-located to Britain in the aftermath of the war to attend the London School of Economics and to work within the Pan-African movement with longtime organizer and journalist George Padmore.

Nkrumah immediately plunged into activism surrounding the building of a Fifth Pan-African Congress that was held in Manchester in October 1945. This became the most representative of the Pan-African Congresses which had been held since 1893 in Chicago. Other meetings took place in London, Paris, Brussels, Lisbon and New York between 1900 and 1927.

Nkrumah was a leading figure in the Fifth Pan-African Congress as its secretary. The president of the Congress was W.E.B. DuBois and Padmore was its Chairman.

This gathering was attended by 200 delegates from various regions of Africa and the Diaspora. Some of the other leading personalities involved were Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, Peter Abrahams of South Africa, J.S. Annan, of Gold Coast Railway Union, Soyemi Coker of the Trade Union Congress of Nigeria, I.T.A. Wallace Johnson of Sierra Leone representing the West African Youth League, E.P. Marks of the Colored Workers’ Association, Amy Ashwood Garvey of Jamaica (the first wife of Marcus Garvey), and Alma La Badi of Jamaica.

Bold resolutions and reports were presented and approved by the Congress. Trade union organizations from numerous Caribbean nations including Trinidad, Grenada, Antigua, Barbados and Jamaica were represented.

In a report entitled “Imperialism in North and West Africa, Nkrumah is cited as saying that “Six years of slaughter and devastation has ended, and peoples everywhere were celebrating the end of the struggle not so much with joy as with a sense of relief. They do not and cannot feel secure as long as Imperialism assaults the world. He indicted Imperialism as one of the major causes of war, and called for strong and vigorous action to eradicate it.”

Nkrumah returned to the Gold Coast in December 1947 to work as an organizer for the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC), an anti-colonial coalition that was dominated by traditional leaders and professionals allied with British imperialism. After one year, he would become estranged from the UGCC where he had formed the Committee on Youth Organization (CYO).

On June 12, 1949, Nkrumah supported by the CYO, trade unions, market women and progressive intellectuals, formed the Convention People’s Party (CPP) which led the country to national independence on March 6, 1957. Ghana became a republic on July 1, 1960.

Annotated Bibliography of the Major Published Works of Kwame Nkrumah

Toward Colonial Freedom (1945)—Nkrumah had written the draft of this anti-imperialist monograph that was influenced heavily by Marx and Lenin before leaving the U.S. in May 1945. When he arrived in England he raised enough funds to publish the book on his own. It was later published in Ghana after independence in 1962.

The Accra Evening News (1948-1966)—This was the newspaper of Kwame Nkrumah and was formed in October 1948 when he was being removed from his official position with the UGCC. The CYO published and circulated the newspaper which was attacked by the British colonialists and African reactionaries in the Gold Coast. Nkrumah said “I fail to see how any liberation movement could possibly succeed without an effective means of broadcasting its policy to the rank and file of the people.”

Ghana: The Autobiography of Kwame Nkrumah (1957)—This book was issued at the time of national independence and includes Nkrumah’s personal account of his political development and the struggle for liberation.

I Speak of Freedom (1961)—A collection of speeches by Nkrumah from 1951-1960. The talks largely centered on the strategies for national liberation movement building and the construction of independence governments in the post-colonial period.

Africa Must Unite (1963)—This book was on the problems and prospects for African continental government. The book examines the economic exploitation of Africa by imperialism and the dangers of military and political alliances with the imperialist states. Nkrumah calls for socialism as the economic system that can lead Africa to genuine freedom. The book was published to coincide with the formation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU and was circulated to all heads-of-state in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia on May 25, 1963.

Consciencism: Philosophy and Ideology For Decolonization (1964)—This draws upon Nkrumah’s background in philosophy. He advances the notion of the three Africa’s: traditional with Christian and Islamic influences. He says that the incorporation of positive aspects of all three traditions is necessary to bring about a synthesis of history and culture leading to Pan-Africanism and socialism. The book was revised in 1969 to place stronger emphasis on the class struggle after the military coup of 1966 that deposed Nkrumah.

Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism (1965)—A comprehensive study on the role of imperialism in Africa. The book targets U.S. imperialism as the central impediment to African liberation and socialism. After publishing the book, which coincided with the OAU Summit in Accra, the U.S. State Department issued a letter of protest. Nkrumah’s government was toppled just four month later at the aegis of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the State Department.

The Rhodesia File (Written in 1965, not published until 1974)—This is a collection of speeches, memorandum and documents on the struggle against settler colonialism in Rhodesia (later named Zimbabwe after independence in 1980) The Nkrumah government in 1965 broke diplomatic relations with Britain over the failure to take action against the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) of the Ian Smith racist regime in Salisbury. The CIA-engineered coup seized upon Nkrumah’s militancy related to the Zimbabwe situation and told rebel soldiers that the Ghana government under the CPP was planning to send them to fight in Rhodesia.

Challenge of the Congo (1967)—This book is perhaps the most comprehensive and detailed account of the independence and post-colonial crisis in Congo, where the first Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba was deposed and later assassinated. The book was published after the coup of February 24, 1966 when Nkrumah was living in Conakry, Guinea and serving as Co-President alongside Ahmed Sekou Toure.

Voice From Conakry (1967)—This book contains the transcripts from radio broadcasts by Nkrumah between March and December of 1966 when he first took residence in Guinea after the coup. The broadcasts were done over Radio Conakry, the Voice of the African Revolution, and beamed directly into Ghana. The broadcasts created panic among the U.S.-backed military and police regime causing the confiscation of portable radios inside Ghana.

Axioms of Kwame Nkrumah (1967)—A collection of short extracts from the writing and speeches of Kwame Nkrumah. It is subtitled: Freedom Fighters Edition.

Dark Days in Ghana (1968)—Nkrumah’s detailed account of the forces that staged the coup in 1966. The book also chronicles the political and economic debacle after the coup and the resistance to neo-colonial rule.

Handbook of Revolutionary Warfare (1968)—A compelling guide to the armed phase of the African Revolution. Nkrumah identifies imperialism as the principle enemy of African peoples. He outlines the various classes and sectors within African society and their role in the revolution.

The Struggle Continues (1968)—A collection of six pamphlets written in 1949 (What I Mean by Positive Action) and five others completed in 1967-68 on The Specter of Black Power, The Struggle Continues, Ghana: The Way Out, The Big Lie and Two Myths.

Class Struggle in Africa (1970)—This book is a succinct overview of the class forces in Africa and their relationship to world imperialism. Nkrumah states that the Black Revolution in the U.S. and the Caribbean is part and parcel of the African Revolution on the continent. The role and status of workers, students, the police and military are examined.

Revolutionary Path (1973)—This book was published after Nkrumah’s death which took place on April 27, 1972. The book is a collection of excerpts from previously issued works as well as speeches. Each section has an introduction by Nkrumah. His last statement from October 1971 is reprinted at the conclusion of the book.

Kwame Nkrumah: The Conakry Years (1991)—This book was compiled by the literary executor of Nkrumah’s estate, June Milne, who had worked as a research assistant to him since his days in power in Ghana. Milne was the director of Panaf Books Limited, which published his literary works after the coup in 1966. The book contains correspondence with Milne and other leading figures such as Shirley Graham DuBois, Stokely Carmichael and others.

The Significance of Nkrumah Today

There are tremendous lessons from the life and times of Kwame Nkrumah. His legacy lives on in many ways including the continued existence of the African Union and the greater identification of Africans in the Diaspora with their national homeland.

Nkrumah warned that if Africa did not move towards socialism and continental unity the gains of the independence period would be soon lost. Today with the presence of the U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) and the intensification of militarism and economic exploitation, there is no other choice but to fight for scientific socialism and revolutionary Pan-Africanism.

In his book “Class Struggle in Africa” he says that “Under neocolonialism a new form of violence is being used against the peoples of Africa. It takes the form of indirect political domination through the indigenous bourgeoisie and puppet governments teleguided and marionetted by neocolonialists; direct economic exploitation through an extension of the operations of giant interlocking corporations; and through all manner of other insidious ways such as the control of mass communications media, and ideological penetration.” (p. 87)

Nkrumah concludes this book by noting that “The total liberation and the unification of Africa under an All-African socialist government must be the primary objective of all Black revolutionaries throughout the world. It is an objective which, when achieved, will bring about the fulfillment of the aspirations of Africans and people of African descent everywhere. It will at the same time advance the triumph of the international socialist revolution, and the onward progress towards world communism, under which, every society is ordered on the principle of—from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.” (p. 88)

No comments:

Post a Comment