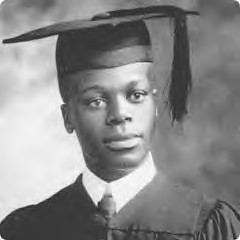

Pixley Ka Isaka Seme, the first South African to graduate from Columiba University in 1906. He would later co-found the African National Congress in 1912., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

The cradle of South African politics

Thursday, 16 August 2012 00:00

Dr F. M. Lucky Mathebula

It is oftentimes unusual to have a name of a locality being analysed for its political significance and meaning rather than what it means for the residents of the area.

Mangaung, South Sotho for a place of cheetahs, is metaphoric in its relationship with the political developments of South Africa. It is a foundational home to the ruling African National Congress of South Africa and the erstwhile National Party which ruled for an uninterrupted 46 years.

Among the known characteristics of a cheetah, lengau, are its speed, agility, patience and an insatiable capacity to rear its young to meet realities of the terrain’s they must operate under.

Mangaung, to South Africa, will always be about the “foundational location” of the nationalist “character” of the country. It represents a place where the two “nationals” were formalised into movements that shaped the political topography of present-day South Africa.

The socio-economic texture of the country owes its origins to Mangaung, and the decisions taken therein at the turn of the 19th century. The men and women who met in Mangaung in 1912 and 1913 respectively remain the founding architects of the nationalist aspirations the country pursued along two distinct paths.

It was at the turn of the century that an almost “all-whites” war was concluded with the treaty of Vereeniging treaty in 1902, which defined “peace-time” South Africa. The terms of the treaty became instructs to the 1909 National Convention which formalised the provinces of the Cape, Natal, Orange Free State and Transvaal into a geo-political space called the Union of South Africa.

The terms of a Convention, particularly those that excluded black people in the settlement and wanted the continuation of British colonial influence, led to a nationalist reawakening that got formalised into the South African Native National Congress and the National Party in 1912 and 1913 respectively, and, in Mangaung.

The anti-colonial sentiment became the only intersecting goal of the nationalist movements; it was the attitude of the different movements to the development coalition and consensus that defined how the anti-colonial struggle was to be waged.

In Mangaung, the two Nationalist movements declared their intent to repudiate colonialism and replace it with a “democracy” that will have as its central interest, the emancipation of “die volk” (NP) from British domination and “black people” (SANNC) from white domination.

Whereas the SANNC declaration was in the main about being excluded in the 1909 “settlement”, the National Party’s declaration was about a narrow “self-identity” and “self-determination” hell-bent and “white supremacy” and “African subjugation”. The non-cohesive nature of these intents in respect of building a South Africa that “belongs to all who live in it” created a two-stream “anti-colonial struggle” that collected along its paths “strange breeds” of ideological persuasions still bedevilling post-1994 South Africa today.

Mangaung, then Bloemfontein, and incidentally as legend would have it, also named after a Koi Korana chief who inhibited the area, creates some political indigenousness of South Africa that still needs to be recorded in a manner that redefines the country’s historical outlook.

Mangaung represents therefore the beginning of a socio-economic and political journey of South Africa that instructed its development, economic prosperity speaking.

The historic Pixley ka Seme inspired anti-tribalism declaration that themed the formation of the ANC, and its diametrically appositional Afrikaner tribal Nationalist Party declarations, in Mangaung, grew to become the most foregrounded nodes of political tensions in South Africa; these are still keynotes of all manner of political discourse.

The legislative decorum of South Africa, which is by the way not a true reflection of the National Party and ANC nationalist construct, has its origins in the declarations made by the founding fathers of those movements in Mangaung.

The Mangaung cohort of leaders, the thinking concentrates that operated then, the visions about South Africa that inspired the then leadership and the economic balance of forces that structured the then “ideological firmaments, generated responses that had the government of South Africa as the price of all politics”.

The Nkosi Sikeleli Africa and Die Stem murmuring that reverberated in Mangaung in 1912 and 1913, were not only a call to unity and freedom for the “people of South Africa” but a realisation that no “government could claim authority over the Union of South Africa unless it is based on the ‘free will’ of its citizens”.

The Mangaung halls, atmosphere and environment are thus not a stranger to hosting congregations of thinking men and women. Mangaung as a locality understands the importance of providing a venue for long-term thinking about South Africa, notwithstanding what that thinking is all about.

Vision of South Africa, even if some were later proved to be not only an aberration of human thought but also a crime against humanity, have resonance with Mangaung.

It is not a coincidence that the Supreme Court of South Africa, an institution that has shaped the infrastructure for our current rule of law based constitutional dispensation is in Mangaung.

The judgments of the Supreme Court have for a long time provided a semblance of justice in the country albeit based, in many instances, on a system that could not be justifiable, apartheid. The practice to have the rule of and by law that is not vulnerable to the whims of human excitement and agitation was thus anchored in Mangaung for a long time.

As the ANC will be congregating again in Mangaung it needs to do so understanding the potential of the area to produce two-streams of thoughts about the same aspiration.

Being the oldest in the visioning of a South Africa that promoted equal opportunities with managed equal outcomes, a South Africa that is part of a global economic system, a South Africa that has a “then settler” community which has embraced its traditions and customs as their own.

The ANC needs to be warned on how it approaches the visioning familiar halls of Mangaung. The non-racial character of the ANC, its standing as the leader of the liberation movement still underway, and its recently emboldened status as leader of the continental development agenda should circumcise its politically young into a post-winter maturity expected out of its Mangaung 2012 Elective Conference.

The Mangaunisation, a condition where a political formation is faced with the challenge of responding to a national condition in a manner that does not benefit the incumbents but builds lasting tracks for future generations to inherit and continuously optimise, of South Africa at the turn of the previous century was the responsibility of ANC delegates.

The then delegates, based on what the ANC became, understood their calling, mandate and accountability, and thus did not disappoint.

They were so focused on the tasks at hand to an extent that conference elected a president who was not at the conference, a clear indication that there was a set criterion as to who could lead such a gigantic vision.

The timelessness of the 1912, and subsequent conferences, stands out as evidence of the “breed” and quality of leadership and delegates that swelled the ranks of the ANC and occupied the conference seats in the halls of Mangaung.

Notwithstanding the racial vector of their declarations, the 1913 National Party conference, also within the halls and environment of Mangaung, remain the foundational praxis within which the development of “white South Africa” and “South Africa” is analysed.

The manner in which that cohort defined “die volk” became an ideological instruct to the 1948 and beyond National Party generation that accelerated the architecture of present day South African economic fundamentals.

The incorrectness of excluding the majority of South Africans that was finally laid to rest by the Mandela-De Klerk accord that produced the current constitution remains the foremost residue of the 1912 and 1913 Mangaung conferences.

Like all residuals the 2012 Mangaung Halls should settle once and for all the definition of “who are really South Africans” and “what is national” in the African National of the Congress called the ANC.

Fortunately for us in the nation, Mangaung is again with us. The Zuma-led cohort of ANC leaders, with all its challenges, needs to rise above the narrow in-party factional interests that relegate the tasks at hand.

Aimed with the might of the state, resources from the state revenue account as well as a significant political mandate as at the last election, the ANC cannot disappoint the halls of Mangaung with the content of its discussion.

It is maybe right to indicate at this point that after its inauguration, the 1910 Union government prioritised economic policy-making.

The 1913 Land Act, which by the way also received National Party objection until it was made clear to them they are part of the development coalition, purely on their whiteness, represents the economic resolve that led to the South African war and the subsequent disenfranchisement of blacks.

Mangaung therefore means a place where visioning about South Africa needs to be made. South Africans expect from Mangaung an ANC that will articulate a vision for the country, a vision that “truly” makes South Africa to not only belong to those who live in it, but one that makes everyone living in it to want to live in it.

Like a cheetah, whose beauty and characteristics represents a combination of colour schemes that supports its ability to blend with its environment, the ANC should emulate the cheetah as it congregates at the place of cheetahs, Mangaung.

Policies that will emerge in Mangaung must have the force of pulling the end state of the next 100 years closer to this generation of South Africans, thus making our history a source of inspiration to move forward.

Our Mandela instruct of “never, never again”’ must permeate to the many “strange” things that that seem to be settling as a political sub-culture in the country’s politics.

Dr F. M. Lucky Mathebula is a businessman with active ownership in a number of companies. He is a policy analyst and a strategic planning consultant. He can be contacted on mathebula@yebo.co.za

No comments:

Post a Comment