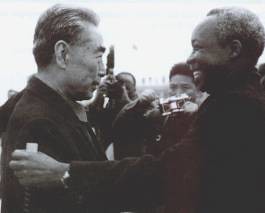

Chou En-lai former Chinese Premier along with former President of Tanzania, Mwalimu Julius Nyerere. Nyerere understood the land question in Zimbabwe., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

Thursday, 23 May 2013 00:00

Guy Anold

THE disunity over major issues and individual quarrels between members that emerged at the OAU summit in Mauritius in June 1976 raised once more the question as to whether the OAU was about to break up.

But as Nigeria’s Commissioner for External Affairs, Joe Garba, said earlier in the year at the time of the Angola Summit: “The OAU is the one thing we’ve got that unites us.”

It is always easy to belittle the activities of the OAU: any international gathering comprising more than 40 countries is more likely to expose differences than discover views in common. Once the base factors shared by OAU members have been taken into account, there are at least as many inter-Africa problems that will divide as will unite. The base factors, however, are important. There is the business of being African, of sharing a continental background; there is the question of poverty and development, of recent colonial exploitation and the need for a common front to the rich developed world; there is the question of racism and the common opposition to white minority rule in the South.

Yet, given the unity that arises from a more-or-less common approach to these questions, there are otherwise no obvious reasons why the OAU’s members should find more in common with each other or less to quarrel about than any other group of comparable size and background. And, that being the case, the real wonder is that the organisation has managed to survive as well as it has for as long as it has.

The OAU Charter talks grandly of governing Africa; what the organisation in fact provides for its members is a working body that is of limited practical use for some of the time.

Many of its procedures are high-sounding and ineffectual while all too often its sessions are dominated by meaningless speeches and slogans. Yet it has also served as a bridge between heads of state and members who otherwise would have continued at loggerheads and it has made possible reconciliations which otherwise would not have been achieved.

More importantly, it has helped produce a united African voice in the larger world forum of the United Nations.

Secretary General

The fact that there is no forceful OAU programme or policy on many matters of keen concern to all members lessens even that authority which the organisation does possess. The basic problem is that no effective power has been given to the secretary general and no country has shown any desire to surrender real authority to the organisation either.

The secretary general has four assistant secretaries-general who are all political appointees and all have to agree before any action can be taken. To be more effective, the OAU needs an executive as opposed to an administrative secretary general. It is indicative of how little members would surrender authority to the organisation that the 21-man Commission of Mediation, Conciliation and Arbitration, which was set up to adjudicate interstate disputes, folded up in 1970, after three years of total inactivity because no state was prepared to submit to its authority.

Despite the unwillingness of members to surrender any power to the organisation, the OAU did still have some achievements to its credit in its first 10 years; there were solutions to disputes; the bringing of Africans together; the establishment of a joint African voice; and the regular meetings of heads of state which often led to agreements that otherwise were unlikely to have taken place.

The search for unity in Africa, however, has been as difficult and elusive as comparable searches (where they have taken place at all) anywhere in the world. At least Africa tries.

Liberation movements

The major issue which over the years has been productive of more unity in the organisation than any other is that of Southern Africa and yet the failures in this field — for example, to bring warring liberation movements together — are not faults of the organisation; rather, they are the result of asking the OAU to do more than it conceivably could.

Always it has been a question of power. At the November 1966 summit that was dominated by the question of Rhodesia and at which no progress was achieved, Nyerere remarked bitterly and accurately that Britain and France had more power in the OAU than did the African states: “. . .This is sad for Africa. Africa is in a mess. There is a devil somewhere.”

Efforts to give the OAU teeth have failed; there is as yet no sign that members want true unity in Africa — that is, the kind of unity that entails the sacrifice of power to a central authority. Over the years the OAU has learnt some caution. The 1965 resolution that members should break diplomatic relations with Britain over Rhodesia — of 36 members, only nine obeyed the resolution — was a farce that taught subsequent caution about such a demonstration of principle, for when it comes to the point it was pragmatism taking a look at British power that won the day.

The formation of the OAU itself was a reaction to the tendencies of the early 1960s that threatened to split the continent into a number of rival and contending groups.

The coming into being of the OAU at least signified an African desire for joint diplomacy and continental handling of problems. The weaknesses of the OAU are certainly no greater than those pertaining to the UN; at least no one possesses a veto. But fundamentally the organisation can only act according to the political will of its members. Over a wide range of topics, members do not wish to act at all — so the organisation does nothing.

Over a few topics it does act or would if the collective will of the members could actually be translated into action but that, of course, also requires power and in fact very little power resides in the hands of OAU members.

— New African.

No comments:

Post a Comment