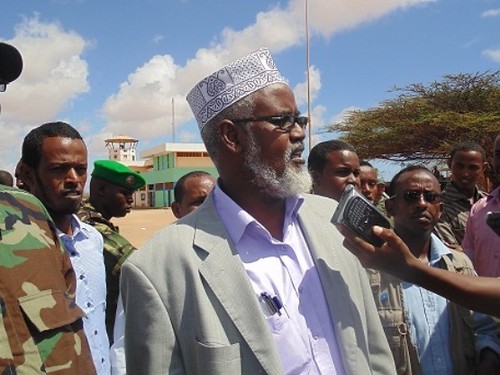

Ahmed Madobe was elected in May 2013 as the president of Jubaland in southern Somalia. He is seeking support from Puntland., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

New Problems for Somalia's Jubaland

Friday, 12 July 2013 05:35

Somalilandsun -The Institute for Security Studies (ISS) in Nairobi published on 11 July 2013 a brief analysis titled "A New Solution that Brings New Problems for Somalia's Jubaland" by Emmanuel Kisiangani, senior researcher, and Hawa Noor, research intern, at ISS.

A new solution that brings new problems for Somalia's Jubaland

By Emmanuel Kisiangani

On 15 May 2013, Sheikh Ahmed Mohamed Islam, aka Madobe, a former warlord and the leader of the Ras Kamboni Movement (a Somali militia group), was elected president of Somalia's strategic region of Jubaland. In a move that conjured up images of Somalia's separatist northern regions of Somaliland, Puntland and Galmudug, the election of Madobe, an ally of the Kenyan Defence Forces (KDF), has raised questions about legitimacy and federal jurisdiction in Somalia and stirred fears of renewed fragmentation and loss of influence by the nascent regime in Mogadishu. In turn, it is alleged that the Somali federal government in Mogadishu covertly supported other candidates such as former warlord Colonel Barre Hirale in order to undercut Madobe and improve the political fortunes of the Mogadishu-based government.

Nearly two months after Madobe's election by the majority of the 500 delegates who gathered at the Jubaland conference in Kismayo, the situation in the important port city and the fertile region of Jubaland remains precarious. It threatens to undermine the advances made in the fight against al-Shabaab and state-building efforts by the federal government. Of concern too is Mogadishu's persistent accusations of non-impartiality by the Kismayo-based African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) Section Two forces, most of whom are from the KDF, and its potential effect on sub-regional relations.

The newly elected Somali federal government president, Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, has already warned that Somalis must remain united and that federalism, as provided for in the country's constitution, can only provide a constructive platform for promoting unity as opposed to secession.

Speaking for the first time since the Jubaland conference, Hassan called on the people of Jubaland to support the central government as the only legitimate governing body of Somalia.

Jubaland (which consists of the Gedo, Lower Juba and Middle Juba regions) remains largely under the control of al-Shabaab, with the government and AMISOM/Ras Kamboni Movement controlling urban and peri-urban sections. In the months preceding the Jubaland election, Mogadishu attempted to gain control over political dialogue on the formation of Jubaland, but this came to naught due to the Ras Kamboni Movement's leverage. The government then began criticising the process, arguing that it was not inclusive. While the Somali federal government acknowledges that Somalia's provisional federal constitution allows for the formation of a federal system of government, it argues that all the regions of Somalia still fall under the central government.

For its part, the new Jubaland administration refutes the allegation of having formed an autonomous government and claims that its search for a strong administration in Kismayo is in line with the federal constitution and that the Somali federal government had been invited to participate in the dialogue process.

Jubaland (formerly Azania) is geo-politically and economically strategic because of possible gas and oil deposits, its charcoal industry and its fertile agricultural land, all of which make it attractive to both local clans and neighbouring countries. For Kenya, a Jubaland backed by a strong administration could provide a buffer zone solution to security problems in its north-eastern region, and in particular to its ongoing Lamu Port and South Sudan Ethiopia Transport Corridor infrastructure project.

Kenya, however, finds itself in a difficult position, having played a central role in Somalia's various peace processes but needing the support of the Ras Kamboni Movement in its intervention in Somalia against al-Shabaab. The implication of this is that Kenya cannot easily disregard its ally, particularly given the role each is playing in pacifying southern Somalia. However, supporting the formation of Jubaland and Madobe's leadership is seen as a betrayal of the same national government that it helped to create.

Kismayo also holds geostrategic possibilities for land-locked Ethiopia, as it could provide it with a new route to the Indian Ocean. The formation of a new Jubaland administration, however, is a double-edged sword for Ethiopia due to clan affiliations that continue to define cross-border relations in the region.

The majority of Jubalanders, including its new leader, are from the Ogaden clan, which also occupies the Ogaden region in eastern Ethiopia (bordering Jubaland). Thus an independent Jubaland could lead to Ogaden National Liberation Front rebels increasing their demands for secession from Ethiopia.

With the ongoing blame game over Kismayo, the stand-off has the potential to destabilise southern Somalia and re-invigorate al-Shabaab. It can also undermine Somalia's state-building process and relations with neighbouring states. The federal government in Mogadishu has legitimate fears about the potential threat to its influence over parts of Somalia, but the Ras Kamboni Movement has contributed significantly to fighting al-Shabaab and the two parties need to find a middle ground. There have been reports that the federal government is willing to compromise by granting the Ras Kamboni Movement an interim regional leadership, which is quite encouraging.

Importantly, the federal government needs to initiate formal dialogue, with the support of the United Nations, over Kismayo – dialogue that should include neighbouring member states of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD). That way the parties can address their perceived grievances, which at the moment do not seem very entrenched. The federal government also needs to move quickly to revisit the question of its interim federal constitution, whose merits remain divisive. Otherwise, it will do itself more harm by engaging in proxy warfare over Kismayo, in the face of momentous priorities that at a very basic level include extending its influence beyond Mogadishu and basic service provision under tenuous political circumstances and with serious resource constraints.

Emmanuel Kisiangani, Senior Researcher and Hawa Noor, Research Intern, Conflict Prevention and Risk Analysis Division, ISS Nairobi.

No comments:

Post a Comment