Recalling Africa’s Harrowing Tale of Enslavement

30 MAR, 2018 - 00:0

The “middle passage” describes the harrowing journey lasting several months from Africa’s west coast to the Americas during which millions of Africans, packed like sardines in the slave ships, died of thirst, hunger, rough seas and sometimes from the sheer brutality inflicted by the European slavers

George Pavlu

Correspondent

IN his book, “Slaves and Slavery”, published in 1998, the British writer Duncan Clarke defines slavery as “the reduction of fellow human beings to the legal status of chattels, allowing them to be bought and sold as goods”.

This, in essence, is what both the Arabs and Europeans did to Africans, to justify the shipping of millions of Africans as slaves to far-away lands in Asia (in particular, the Middle East) and the Americas.

“The African slave trade, surely one of the most tragic and disturbing episodes in the history of mankind,” Clarke writes, “had its origins in the intervention of forces from the civilisations that developed in the regions of the Mediterranean sea – today’s Europe and the Middle East – into the arena of the more fragmented civilisations of sub-Saharan Africa.

“Africa became a source of slaves for the cultures of the Mediterranean world many centuries before the discovery of the Americas, but it was that discovery and the resulting shift in focus towards the Atlantic that prompted the culminating explosive growth in slavery with such tragic effect.”

Slavery, in fact, was a central feature of life in the Mediterranean world, especially in Mesopotamia, ancient Egypt, Greece, Imperial Rome and the Islamic societies of the Middle East and North Africa.

“The most important source of slaves in medieval Europe,” Clarke’s research shows, “was the coast of Bosnia on the eastern shores of the Adriatic Sea. The word “slave” and its cognates in most modern European languages is itself derived from “sclavus” meaning “slav”, the ethnic name for the inhabitants of this region . . .

“For various reasons, including the harshness of the terrain and endemic warfare among local clans, Bosnia proved the most convenient and long-lasting of these slave-supplying regions. Whichever clan gained a temporary upper hand was always willing to sell its captured rivals in exchange for the goods of the Mediterranean world in the markets of the ancient Romanised city of Ragusa (present day Dubrovnik). From there, Slavs were shipped as slaves by Venetian merchants, to supply new markets in the Islamic world.”

Thus, “for the Islamic world,” Clarke continues, “Slavs provided the major source of slaves in the 250 or so years between the defeat at the battle of Poitiers in AD 732 that forced the consolidation of their dramatic conquests across North Africa and the Iberian peninsula, cutting back the flow of war captives and the expansion of the import of black Africans across the Sahara from around AD 1000.”

The trade in slaves ended when the Ottoman Turks conquered the region in 1463.

“The effective closure of the last major source of slaves on the European continent,” says Clarke, “thus coincidentally took place at the same time as the Portuguese explorations of the West African coast, which were to open up the second and most devastating route for the exploitation of Africans as slaves.”

Figures on the Arab slave trade in Africa are hard to come by, but the historian Paul Lovejoy estimates that some 9,85 million Africans were shipped out as slaves to Arabia and, in small numbers, to the Indian subcontinent. Lovejoy breaks his figures down as follows:

Between AD650 and 1600, an average of 5 000 Africans were shipped out by the Arabs. This makes a rough total of 7,25 million.

Then, between 1600 and 1800, another 1,4 million Africans were shipped out by the Arabs. The 19th century represented the highest point of the Arabian trade where 12 000 Africans were shipped out every year. The total figure for the 19th century alone was 1,2 million slaves to Arabia.

Thus, in terms of numbers, Arabia’s 9,85 million is not far behind the conservative estimate of nearly 12 million African victims of the Atlantic slave trade. Some African historians, though, reject these figures on the grounds that they are too low. They suggest over 50 million Africans were shipped out during the Atlantic trade alone.

According to Lovejoy, another 4,1 million Africans were shipped across the Red Sea to the Persian Gulf and India.

“This trade also, with the notable exception of some Portuguese involvement in the area of Mozambique, and of 18th and 19th century French exports to islands under their control in the Indian Ocean, was largely conducted by Muslims,” adds Duncan Clarke.

Throughout the 19th century, the Omani Arab rulers of Zanzibar shipped hundreds of thousands of African slaves to work on clove plantations on the island. It was this trade that gave Europe and America so much satisfaction, after abolishing their own trade in African slaves, to highlight the wickedness of the Arab slavers who continued to enslave Africans well into the first decades of the 20th century.

Even to this day, Arab slavers are still at work in Sudan and Mauritania, buying and selling black Africans.

David Livingstone, the British missionary/traveller/explorer was so upset by the way the Arabs treated their African slaves that he wrote back home in 1870:

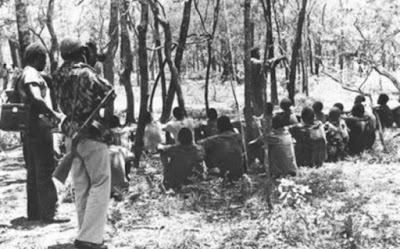

“In less than I take to talk about it, these unfortunate creatures — 84 of them, wended their way into the village where we were. Some of them, the eldest, were women from 20 to 22 years of age, and there were youths from 18 to 19, but the large majority was made up of boys and girls from seven years to 14 or 15 years of age.

“A more terrible scene than these men, women and children, I do not think I ever came across. To say that they were emaciated would not give you an idea of what human beings can undergo under certain circumstances.

“Each of them had his neck in a large forked stick, weighing from 30 to 40 pounds, and five or six feet long, cut with a fork at the end of it where the branches of a tree spread out.

“The women were tethered with bark thongs, which are, of all things, the most cruel to be tied with. Of course they are soft and supple when first striped off the trees, but a few hours in the sun make them about as hard as the iron round packing-cases.

“The little children were fastened by thongs to their mothers.

“As we passed along the path which these slaves had travelled, I was shown a spot in the bushes where a poor woman the day before, unable to keep on the march, and likely to hinder it, was cut down by the axe of one of these slave drivers.

“We went on further and were shown a place where a child lay. It had been recently born and its mother was unable to carry it from debility and exhaustion; so the slave trader had taken this little infant by its feet and dashed its brains out against one of the trees and thrown it in there.”

Such was the brutality meted out to the Africans by the Arabs. Like the Atlantic trade, the Arabian trade’s “middle passage” was equally as horrible and terrifying.

The “middle passage” describes the harrowing journey lasting several months from Africa’s west coast to the Americas during which millions of Africans, packed like sardines in the slave ships, died of thirst, hunger, rough seas and sometimes from the sheer brutality inflicted by the European slavers.

In the Arabian trade, the trudge across the Sahara, in leg and neck chains, and as Livingstone describes above, necks in large forked sticks and hands tied with bark thongs, was particularly harsh on the African slaves.

Says Duncan Clarke: “The hardships of these long marches across the desert were considerable and much later travellers reported that the routes were lined with the parched skeletons of those who succumbed to exhaustion and thirst along the way.”

The Arab slavers did not only march their African captives to Arabia, they also sometimes sold them to European slavers.

In modern times, the popular image of African slavery springs from the vision of a tormented male suffering under the lash of unceasing labour on some “New World” sugar plantation.

Yet the real face of servitude finds its focus in the forced migration of millions of girls and young women across the Sahara and the Horn of Africa in to the institutions of Islamic concubinage.

Why they preferred women

While in the European “New World”; the measure of a man’s stature was mapped out and calibrated on the physical dimensions of empire built upon the sinews of forced masculine labour, in the Islamic Orient wealth was a reflection of prestige, young girls the vessel of male hubris , the mats of male pleasure ground, the malleable material to be shaped to the master’s will.

Thus, women slaves in the Arab world were often turned into concubines living in harems, and rarely as wives, their children becoming free. A large number of male slaves and young boys were castrated and turned into eunuchs who kept watch over the harems. Castration was a particularly brutal operation with a survival rate of only 10 percent.

“The combined effect of all these factors,” says Duncan Clarke, “was a steady demand for slaves throughout the Islamic world, which had cover story to be met from wars, raids or purchases along the borders with non-Islamic regions. Although some of these slaves came from Russia, the Balkans and central Asia, the continuing expansion of Islamic regimes in sub-Saharan Africa made black Africans, the major source.”

So invasive was the practice of slavery into the economic, political, demographic, cultural, social and religious life of Africa and persisted for so many centuries, that while its effects varied both geographically and temporally in intensity, slavery outdistances in scale and scope any single or combination of disasters — natural or man-made, which descended upon the continent.

Slavery unquestionably checked population growth in Africa and consequentially placed tremendous pressure upon gender and marital relationships during the three critical centuries of European expansion to global domination.

In this sense, the feminine-oriented Arab slave trade, though neither motivated nor executed with economic benefits as prime objective, caused far greater demographic damage and consequently greater economic decline, with its excessive poaching of the reproductive potential of the harvested areas.

The impact on Africa

No people are blank slates upon which can be inscribed untold miseries and expect no account thereof. The Arab slave trade began long before the Islamic conquest of Africa, remained at relatively low level compared to the Atlantic slave trade and did not become illegal or abolished, and was maintained till well after the colonisation of Africa. The Arabian trade was outlawed in Ethiopia only in 1935 in order to gain international support against the Italian invasion.

In the Atlantic trade, the slaves came predominantly from Africa’s west coast with a male/female ratio of two-to-one. In the Arabian trade, the slaves were exclusively from the Savannah and the Horn of Africa, and favoured females over males at a ratio nearing three-to-one.

When slavery in the Black Sea area (the traditional source of the best grade female slaves for the Arab market) dried up, it triggered an even greater demand for Ethiopian “red” slaves, in particular the Galla and Oromo on account of their unquestioned beauty and willing sexual temperament.

And while the Europeans paid a higher price for male slaves than females, the reverse was the case with the Arabs. Moreover, while the European/New World slavers profited mainly from male labour, the Arabs saw profit in sexual satisfaction/reproductive potential. (Offspring of the union between Islamic master and female slave was born free, out of respect of the child’s Islamic paternity. Any offspring of the Atlantic trade were born into slavery).

“The laws of Islam ,” as the historian Hugh Thomas attests, “were in some ways more benign in respect of slavery than were those of Rome. Slaves were not to be treated as if they were animals. Slaves and freemen were equal from the point of view of God. The master did not have power of life and death over his slave property.”

But to the Africans shipped across the Red Sea, the “benign” Islamic laws provided little comfort — they were still slaves of Islamic masters who had unfettered sexual access to them (if they were female) or castrated and turned into eunuchs (if they were men).

The upshot of this gender profile of the respective slave-classes in the Atlantic/New World and the Arab/Oriental world explains the large and visible population of African origin in the New World where sexual relations between white and black was the exception while in the Arab world where miscegenation was the practice, the slave trade has left few visible traces.

So where are the descendants of the African slaves sent to Arabia/Orient? There are no large concentrations of them, anywhere in the Middle East or Asia.

Five years ago, a British TV documentary showed how poorly the descendants of African slaves in Pakistan are treated by the authorities. The racial discrimination was so bad that one of the African descendants recounted on camera how, even in sport, they were not picked to represent Pakistan at national and international levels no matter how good they were.

Population decline

The demographic effects of Arabian slavery on the source population (those left behind) cannot be overlooked, and specifically when considering the palpable effects on African fertility as a consequence of the grossly reduced female numbers.

To ensure survival, the Africans in the harvested areas adopted a variety of social measures, which were in practice as extreme as the circumstances called for. These revolved principally around the sexual purity of the population’s remaining female reproductive stock, as well as accelerating the female’s reproductive capacity.

Though the number of female slaves exported per annum from the Savannah and the Horn was far smaller than the numbers taken from the west coast in the Atlantic trade, the proportionate impact of the remaining at-brink Savanna/Horn populations was far more severe.

The Arabian trade reached a total of perhaps 5-8% of the source populations – and as mentioned earlier — as the proportion of females harvested was exceptionally high, this resulted in a massive surplus of males in the non-harvested population. Consequently the area experienced demographic stagnation bordering decline.

In 1600, the black African population was some 50 million — about 30% of the combined population of the New World, Europe, Middle East and North Africa. By 1800, the population had fallen to 20% of the total. In 1900, at the end of the slave trade, Africa’s population had fallen yet further to just over 10% of the total — the population now so collapsed as to negatively affect the continent’s labour intensive agricultural output.

In effect, while the populations of Europe and Asia increased year on year, Africa’s population declined dramatically due to the excessive poaching by the slavers, both Arab and European.

In Arabia, the slave class (principally female), unlike the New World slave class, could never maintain itself as a distinct social entity — principally because of miscegenation. This created an even greater demand for more and more new female slaves, and coupled with the frequent natural disasters of drought and famine in the Savannah/Horn, led many African families to offer their young girls in to slavery as a last hope of survival. There are many stories of long lines of hundreds of girls, mainly Oromos from Ethiopia, trudging across the Horn towards the Red Sea seeking enslavement.

Deprived of ideology, ritual, and the African rite of passage to adulthood and social membership, female slaves were uncommonly vulnerable to conversion to Islam (the benefits of manumission aside). Manumission describes a child born of a female slave and a free Islamic father is thus born free.

For the population remaining in Africa, it is in order to embark on some speculation as to what changes the trauma o f slavery may have wrought on African thought. The experience o f sudden turn o f fate (a common experience when confronted by the ever-present threat of slavers) tended to systematically undermine any efforts at long-term planning beyond the constant need to replace lost members.

It is a mistake to equate the bare survival o f Africa with cultural or social or economic stagnation, for the slave trade visited such panoply of tragically interconnected disasters into the lives of every African for centuries, that they have worked their way into the very “racial memory” of the continent and its people, particularly females, that only with time and kindness can it be expunged from the psyche o f Africa.

As one commentator puts it: “Could it be true that the corrosive effects of four centuries of commerce in humans, with its temptation, its in -built opportunism, its reduction of humans to a cash value, its cycles of revenge and its inevitable physical brutality, have built lasting flaws into African pattern of thought and action?”

– New African magazine