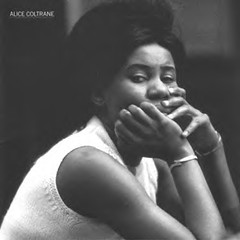

Alice Coltrane as a young woman during her collaboration with John Coltrane, her husband, in the 1960s. Coltrane was 69 when she made her transition in Los Angeles.

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire File Photos.

The Detroiter who became Swami Turiyasangitananda

by Andy Beta

1/24/2007

Spiritual texts tell us that life is change, and change is its only constant. And while it's difficult to mark just when such a metamorphosis occurs in our lives, a change of name generally indicates such a shift, be it confirmation, marriage, divorce or, in the case of musicians, the adoption of a persona like Bob Dylan or David Bowie. For a Detroit jazz pianist named Alice McLeod, each name change through her life intimated a transformation. She was known most famously as Alice Coltrane, second wife to saxophone avatar John Coltrane, and though in her later years she was called Swami Turiyasangitananda, it's as Coltrane that she has been memorialized, having passed away from respiratory failure on Jan.12.

She was born in the house of Virgo on Aug. 27, 1937; the McLeods were a musical household. Alice began her classical training by the age of 7, but was also attuned to jazz, particularly the soulful playing of local Detroit harpist Dorothy Ashby. Ernie Farrow, Alice's half-brother, gigged on bass for the likes of Stan Getz and Yusef Lateef, and Lateef later gave instruction to young Alice as well. Her studies continued at Cass Tech, and she played organ with the gospel choirs at church every Sunday. Later she backed reedman Lateef, as well as jazz guitarist Kenny Burrell, and toured throughout Europe where she studied with bop piano great Bud Powell. She was briefly married to Kenneth "Pancho" Hagood, a Detroit-born jazz crooner who sang with Thelonious Monk and Dizzy Gillespie, and her earliest recordings with vibist Terry Gibbs list her under both her maiden name and Alice Hagood.

After moving to New York in the early '60s and gigging around town, she met tenor saxophonist John Coltrane. The most powerful and iconoclastic figure in post-war jazz, the recordings he made with his classic quartet remain the apex of the decade. That body of work, rendered by Coltrane with bassist Jimmy Garrison, pianist McCoy Tyner, and propelled by the thunder of drummer Elvin Jones, is some of the most volcanic and spiritually affirming music ever set to record. The resultant decades have done little to abate their brilliance.

Alice McLeod became Alice Coltrane in 1966. And while his classic quartet was the epitome of power, grace and ferocity, John Coltrane's restless spirit led him to venture beyond into something less tethered, more spontaneous, more chaotic, more universal. The new openness (or cacophony to its detractors) slowly dissolved his group, and Alice replaced longtime pianist Tyner on the bandstand. As New York Times jazz critic Ben Ratliff noted recently, while she wasn't Tyner's technical equal, she was "fluid and energetic within the group's freer new language." She backed her husband on his later works, performing with him right up until his death from liver cancer in 1967.

When John Coltrane passed, Alice carried the torch that was his musical message, making that fluidity and energy hallmarks of her own style. She incorporated both harp and Wurlitzer organ into her repertoire. Her earliest recordings were made with her late husband's sidemen, including saxophonist Pharoah Sanders and percussionist Rashied Ali. Albums like Ptah the El Daoud and Journey in Satchidananda (both 1970) echoed her husband's work: Modally-rooted and minor-keyed, these sprawling, cathartic explorations similarly referenced Eastern religious traditions. She even contributed to records by the Rascals, Laura Nyro and Carlos Santana.

Though informed by her late husband's incandescence, Alice grew restless too, and began to move out of his indomitable shadow. Her albums from the early '70s, such as Universal Consciousness, World Galaxy and Lord of Lords, remain some of the most head-swimming and audacious of that or any era. Ancient and futuristic, classically structured yet destabilized, the textures and emotions are quicksilver, dizzying and ever-changing. Whether on harp, piano or Wurlitzer, she moves from the pastoral to nightmarish to the transcendent in the span of a few notes. Nominally jazz, Coltrane made space for Indian music, blues, religious chants and Stravinsky too.

Alice Coltrane's spiritual studies continued, to where she receded from music altogether in the late '70s to concentrate on Vedic scriptures. Intermittently, she would return to play with her son Ravi Coltrane, even releasing Translinear Light in 2004. At her ashram in Woodland Hills near Los Angeles, she became a spiritual teacher, Swami Turiyasangitananda. Translated from Sanskrit, it means "the highest song of God." One could say that her earthly name meant that as well.

See Also:

George Tysh

In the flesh

Alice Coltrane: Sept. 23, 2006, HIll Auditorium, Ann Arbor.

Andy Beta is a freelance music writer. Send comments to letters@metrotimes.com.

In the flesh

Alice Coltrane, Sept. 23, 2006, Hill Auditorium, Ann Arbor

by George Tysh

1/24/2007

It was transcendent, which is fitting, given her life-long spiritual concerns. Roy Haynes in his 80s had the energy of a twentysomething, the muscles of an Elvin Jones in his prime and the lightning precision of a Tony Williams. Bassist Charlie Haden spread out a huge bottom sound, and spun out one masterfully lyrical solo after another.

At one point, after a ballad duet with Alice, he bowed to her in total affection, and it brought tears to my eyes. Ravi Coltrane managed to be brilliantly himself, even though everyone keeps clamoring for him to be his father. (When he picked up the soprano for a Coltrane tune, it did sound uncannily like John.)

The shock of Alice’s recent passing was tripled after seeing her so recently be so on top of her music, playing piano, organ and synthesizer wonderfully, and speaking eloquently about John’s legacy.

At intermission, there was a slide show, complete with soundtrack, on the life and art of John Coltrane. No one had a problem with such open veneration. And now it seems to have served a double purpose: as a loving recollection and a fond farewell.

Send comments to letters@metrotimes.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment