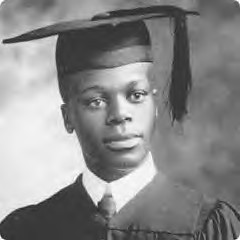

Pixley Ka Isaka Seme, the first South African to graduate from Columiba University in 1906. He would later co-found the African National Congress in 1912.

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire File Photos.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Discovering Seme - Tim Couzens

There are two good reasons for the publication of this book. Firstly, the name of Pixley kaIsaka Seme is today almost completely unknown. Yet it was largely because of his ideas and inspiration that the African National Congress was founded on an overcast but calm day (8 January) in 1912 (the subsequent days of the conference were fine and calm!). There is no full biography of Seme. Indeed, very little is known about his life. This book, then, aims to make available hitherto unknown material connected with his early years and to give insight into a character who was one of South Africa's most important historical figures.

Secondly, the book is intended to honour the memory of Dr Richard Rive, scholar and writer (as well as friend). Richard Rive was brutally killed in 1989; his death was a shock to all those who remembered his affability; the aetiology of his death lies in the complexity of the society in which he lived most of his life. But he left behind him an uncompleted manuscript which contained the story of an important discovery.

Northfield Mount Hermon School (situated in north-western Massachusetts) has, in recent years, established scholarships to bring black South African students to the school for a year's free board and tuition. The school then tries to find money and placings for successful students at universities. Some years ago it broadened the scope of its programme to include several other schools and Counsellor C. Yvonne Jones, organiser of the programme, visited South Africa in 1986 to publicize the scholarship among prospective candidates. In Cape Town she met Richard Rive who had been appointed to Harvard University as Visiting Professor in the Department of English and American Literature for Spring, 1987. She mentioned to him that Pixley Seme had been a pupil at Mount Hermon around the turn of the century.

In February, 1987, Rive visited Mount Hermon as Mrs. Jones's guest. He was shown a file of documents relating to Seme's time at the School. The archivist of the school library, Mrs. Linda Batty, had discovered the file after it had lain undetected for over eighty years. Rive was allowed to have copies of these papers and was thus able to reconstruct details of Seme's early life. He was full of gratitude to Mrs. Batty, Mrs. Jones and Northfield Mount Hermon School and the book which follows has that file as its nucleus.

The originals of the letters, documents and newspaper cuttings are in the school library. The collection contains nine documents (five application forms, one list of Seme's measurements for a suit, one receipt for a catalogue received by him, and two unidentified, undated press cuttings) as well as twenty-seven letters, most of them to Professor Henry Cutler (ten from Seme himself.) Rive appears to have added two further newspaper cuttings to this collection. In March, 1987, he wrote an introduction to the documents but does not seem to have edited them or properly arranged them before his death two years later. In order to complete the whole tale two further important pieces have been added: the first is Seme's prize wining speech 'The Regeneration of Africa', a seminal piece of political thinking for those years just prior to the founding of the ANC; the second is an article published in the July, 1953 edition of Drum magazine in its celebrated series 'Masterpieces in Bronze'. It is something of an historic piece in its own right, written as it was by the recently retired editor of Bantu World and doyen of black journalism, R. V. Selope Thema.

Although the documents relating to Seme are few in number and brief in scope they give a fascinating insight into the early struggles of the man. For students and scholars who might want to follow his footsteps there are several addresses to visit. There are minute details as to his waist measurements and smallness of size: more importantly, there is a clear indication as to how Seme grows in stature, improving his language skills, growing in confidence, becoming a world traveller with expanding knowledge, experience and vision.

Seme was not the first black South African to study overseas (Tiyo Soga was ordained into the Presbyterian Church in Scotland in the 1850s, for instance) but he was one of the earliest. These letters give a hint as to the difficulties, particularly financial, which he and his contemporaries had to face in their pursuit of higher education. They also hint at the kind of networking that w as beginning to develop as a particular class of people began to grow (Seme tried to help the Makanya family place at least one of its sons in a school overseas). Above all, the letters provide some understanding of the determination of Seme to succeed.

Black South Africans have been better served by autobiography than biography. An exception is Brian Willan's wonderful biography of Solomon Plaatje. If one reads Seme's letters in the light of Willan's book and with the help of a somewhat different study, Andre Odendaal's Vukani Bantu! one can begin to appreciate the strengths and weaknesses of a remarkable group of people at the turn of the century - there were the four lawyers (Seme, Alfred Mangena, G. D. Montsioa and R. W. Msimang) who studied overseas and made large contributions to the early ANC; there were the Sogas, the Jabavus, the Rubusanas, the Jordans and many more.1 They often combined many talents - their professions, politics, journalism. Three of them started newspapers. Seme was to be instrumental in the founding of the ANC's newspaper Abantu-Batho in 1912 but one of the tragedies of South African history is that no complete run of this paper survives even though it lasted into the early 1930s.

Seme's activities in 1912 were not only political and journalistic. He saw the need for organisation and unity in the economic sphere, too. Consequently he was the driving force in the founding of the Native Farmer's Association of Africa Limited. The directors of the company met for the first time in the Realty Trust Building in Johannesburg on 25 October 1912 and Seme was made chairman.2 The main purpose of the company was to buy land for blacks to settle on, and in the Wakkerstroom District of the Eastern Transvaal the farms of Daggakraal and Driefontein were bought; the land remains in the hands of the original owners to this day, witnessing the martyrdom a few years ago of the community's leader, Saul Mkize, and the defying of the attempts by the South African government at removal. Not only do we have Seme's political legacy still, in the form of the ANC, but we also have remnants of an economic legacy in these farm communities.

But politicians must never be made into total heroes. Both Rive and Selope Thema implicitly warn us against this. As a lawyer, Seme faced the great odds of racial prejudice initially; later he became more established. But in 1932, the Supreme Court removed his name from the Roll of Attorneys.3 The circumstances are not a credit to Seme.

A number of blacks had lived on the white-owned farm of Waverley in the Pretoria district prior to the passing of the Natives Land Act of 1913. In the 1920s they came under the threat of eviction. They engaged Seme's services but the case was lost both in the magistrate's court and in the appellate division. The lawyer then failed to lodge a further appeal to the Supreme Court within the prescribed three weeks and failed to notify his clients that this was a possibility. The Waverley residents then complained that Seme had not used properly the considerable sum of money they had paid him.

Seme defended himself by saying that some of the money had been paid not as legal fees but to defray expenses which Seme claimed had been incurred trying to 'fight the case politically' by using

'influence to reach the authorities politically.' His clients retorted that they had never paid him anything other than for legal services. The Incorporated Law Society of the Transvaal decided that it must apply to the Transvaal Supreme Court for Seme's removal from the register on the grounds of neglect of his duties to his clients and of 'excessive, unreasonable and unconscionable' fees. Seme failed to appear or defend himself when the case came before the Supreme Court. There is some doubt as to whether this removal from the register had any practical effect because a curious note in a miscellaneous fees book records that he 'never ceased practising'. On 14 April, 1942, he was reinstated as a lawyer.

Sadly, too, the man who launched the ANC ship in 1912, nearly sank it when he was its president in the 1930s. A combination of lethargy and corruption nearly destroyed the organisation then. But in 1943 he made one last important contribution - however inadvertently - to South African history. He took a young man called Anton Lembede on as a law clerk. In that way, it could be argued, Seme became the father of black attorneys in the country. Lembede took the legal profession by such a storm that he kindled the idea of law as a profession amongst many blacks. Lembede was also a key figure in the founding of the ANC Youth League in 1944 and became its first president. He coined the term 'Africanism' and helped define the concept. On 3 August, 1946, Seme informed the Transvaal Lawyers Association that he had sold his law firm to Lembede. Lembede died the following year, however, at the age of thirty-three.4

In the preparation of the documents which follow, idiosyncrasies of spelling, usage and style have largely been retained. Only occasionally have these been changed (e.g. certain abbreviations) in order to make the text or its meaning clearer. The reader should be warned that certain parts of the original documents are unclear or may be missing and that some faults (e.g. in addresses or initials of names) may have crept into the text presented here. No doubt, too, Richard Rive would have acknowledged the help or thanked certain people. That is no longer possible.

They will no doubt content themselves with being the anonymous contributors to the preservation of the reputations of both Pixley Seme and Richard Rive. They must be thanked on Rive's behalf.

I, too, have several people to thank. Firstly, George Seme and D. Seme whom I interviewed many years ago in Ladysmith and Swaziland respectively. Then, Celeste Emmanuel who typed what was sometimes a very difficult text. Most of all, Professor Charles van Onselen and the African Studies Institute of the University of the Witwatersrand who gave me the time and encouragement to undertake this task. There is obviously a great deal more to be done on Seme's life. It is hoped that this small book will encourage a full-scale biography and help whoever embarks on such a worthy undertaking.

A number of addresses in America, England and South Africa are given in the letters and witnessed, for shorter or larger periods, the presence of Pixley Seme. It would be nice to think that, one day, Monuments commissions round the world might commemorate them with plaques or street names. In the meantime we must content ourselves with the memorial of a modest book. In it the voice of Seme, the pioneer newspaperman, the guardian of land tenure, the father of black attorneys, the founder of the ANC, speaks to us after nearly a century and his hand reaches out (with the help of Richard Rive) to nudge our memories lest we forget again.

Notes:

1. For further information on Seme and the founding of the ANC, see T. Karis and G. Carter, From Protest to Challenge, Stanford University, 1977, particularly Volumes One and Four; Odendaal, Vukani Bantu! Cape Town, 1984; P. Walshe, Rise of African Nationalism in South Africa, London, l970; and T. Couzens, C. Seme: 'Lawyer and Leader', in African Law Review, Volume 1, No.1 January, 1987, pp 4-5.

2. Minute Book of the Native Farmers Association of Africa Limited (rescued from a garbage heap and now housed in the African Studies Institute, University of the Witwatersrand).

3. Most of the following information comes from the Supreme Court trial record and from the Transvaal Lawyers Association Register.

4. For slightly fuller information on Lembede, see T. Couzens, The New African, Johannesburg, 1985, particularly pages 258-261.

No comments:

Post a Comment