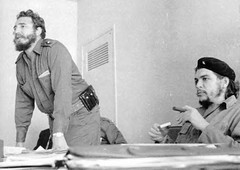

Fidel Castro and Che Guevara during the early days of the Cuban Revolution. The role of the intellectuals in Cuba was a major point of discussion during the early 1960s.

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire File Photos.

the debates recently taking place on these themes in Cuba, where

Fidel Castro's famous discussion, WORDS TO THE INTELLECTUAL has been regularly referred to as a policy reference point, readers here may wish to review those notable remarks. I must say in reading them, they are reminiscent of themes Fidel has also been speaking about in the past two years on a number of occasions.

This intro has not been made available online to my knowledge and

the Guillen speech was particularly interesting as it takes up some

of Cuba's complex racial issues along with the independence struggle, which was at the core of all of the talks in the pamphlet.

Walter Lippmann

===================================================

The Revolution and Cultural Problems in Cuba

Republic of Cuba

Ministry of Foreign Relations

1962: Year of Planning

Forward scanned by Walter Lippmann, January 2007

http://www.walterlippmann.com/fc-06-30-1960.html

This unsigned forward comes from the 1962 Cuban pamphlet published by the Ministry of Foreign Relations. The pamphlet also contained speeches to same conference by the poet Nicolas Guillen, who was also president of the Cuban Union of Artists and Writers (UNEAC) and President Oswaldo Dorticos Torrado. I hope to get them scanned and posted soon.

Forword

The general adherence of all classes in our country to the

revolutionary movement which triumphed on the first of January, 1959. was followed, along with its radicalization and its measures on

behalf of the common people, by first vacillation, then retreat, and

lastly frank repudiation of the Revolution by those who up to then

had enjoyed special privileges. The attitude of the intellectuals who

represented the official culture of previous periods, the culture of

the classes affected by the Revolution, was in keeping with the

attitude of their patrons. These pseudo-intellectuals had a defined

position: they were against the Revolution.

On another side, regarding the Revolution from another point of view,

were the intellectuals who were loyal to it. However, even many of

these honest revolutionaries, enthusiastic workers, men of working

and middle class backgrounds, found that the march of the Revolution, that unfamiliar and rapid march animated by an unsurpassed, constructive rhythm, that tide that swiftly wrote in or erased names, institutions, events, moved only by social justice, that growing wave amazed them, and, in a certain sense, awoke certain fears in them.

When Dr. Fidel Castro, meeting with the writers and artists on the

eve of their First Congress, referred to the Yenan Forum, he revealed

the nature of the cultural problems, in our country.

In the famous Yenan Forum in 1942, Mao Tse-tung could, in the midst of a bloody war of yet unforeseeable results, orient the honest

intellectuals to participate along with men of other classes, the

workers and peasants, in the construction of a new society in China.

In Cuba, when the Revolution began its work, that clear, firm

orientation was lacking, But the Revolution itself proved to be an

exceptional school. Therefore, conscious of the need for all

sympathizers with the Revolution to participate in its work, on

November 19, 1960, the most advanced of the Cuban artists and writers issued a manifesto -- "Towards A National Culture Serving the Revolution". that only a few months later would be regarded as

historic. Its publication marked the beginning of the enthusiastic

work of artists and writers to unite, to take a position, to play a

specific role in the revolutionary process.

The publication of the manifesto was very timely. Events that filled

us with great hopes but that marked directions fraught with

difficulties and obstacles for our Revolution, obliged us all to

formulate clear, unmistakable definitions. The promulgation of the

First Declaration of Havana shortly before by the people of Cuba,

gathered in a National General Assembly, and the adoption of measures such as the nationalization of large foreign and domestically owned companies in Cuba, marked steps of unprecedented importance for the Revolution. It was the exact moment to either state adherence to the cause of the workers and farmers or to rise against them. The Cuban writers and artists formulated an unmistakable declaration. In the November document they proclaimed their irrevocable commitment to the Revolution and to the people.

In the introduction to the statement of their points of view and the

formulation of their immediate program, the writers and artists

considered it their first duty to state their public creative

responsibility to the Revolution and the Cuban people, "in a period,"

they proclaimed, "of united struggle to achieve the complete

independence of our country as a nation." They declared that "the

victory of the Revolution has created among us the essential

conditions for the development of national culture, a liberating

culture, capable of encouraging revolutionary progress."

In accordance with the above premises and the fact that "the unity of

purpose of contemporary Cuban intellectuals is obvious in their works as well as in their of efforts to spread culture among the people throughout the revolutionary period and during the years of struggle that preceded it," the intellectual clearly defined their

revolutionary position.

The immediate program set forth by the writers and artists was in

keeping with these declarations. They stated, as the first point,

that they aspired to the "recovery and development of our cultural

tradition, which is rich in human content and was wrested away from

our people by the colonialists and the imperialists." The second

point of the program was to "preserve, encourage, purify and utilize

our folklore, spiritual wealth of the Cuban people, which the

Revolution is liberating and reevaluating." They added that they

"consider sincere and honest criticism indispensable to the work of

artists and intellectuals," and that they "should try to achieve full

identification between the character of our works and the needs of

our advancing revolution.

The purpose is to bring the people close to the intellectual and the intellectual close to the people, which does not necessarily imply that the artistic quality of our work must thereby suffer." The declaration pointed out, concerning Latin America, that "exchange, contact, and cooperation among Latin American writers. intellectuals and artists are vital for the destiny of our America." And from a still more far-reaching point of view, "Mankind is one. national heritage is part of world culture, and world culture contributes to our national aspirations."

On the basis of these ideas, the preparatory work of he First

National Congress of Writers and Artists began. But the mobilization

in January, 1961, when aggression by imperialism seemed imminent, took many intellectuals to the trenches; the mobilization, and later the aggression itself, with its historic defeat at Playa Giron,

forced the postponement of this great assembly. But the Revolution

advanced constantly. On April 16, the Prime Minister, Dr. Fidel

Castro, proclaimed the socialist character of our Revolution.

The new orientations called for new meetings to be held previous to

the Congress. Dr. Fidel Castro, accompanied by high figures of the

Revolutionary Government, met with. the intellectuals and dealt with

their problems. Many questions dealing with cultural activity were

discussed on June 16, 23, and 30, in the auditorium of the National

Library; there the Prime Minister dispelled fears and clarified the

Revolution's policy in regard to culture and intellectuals.

Thus, with the assurance that artistic freedom was guaranteed

absolutely and totally, the Congress opened on August 18, anniversary of the death of Federico Garcia Lorca. The motto adopted for the Congress proclaimed: "To Defend the Revolution is to Defend Culture." The agenda was based on the program set forth in the November Declaration.

On the opening night, the President of the Republic, Dr. Osvaldo

Dorticos Torrado, spoke about the road that the delegates to the

Congress must take. "Artists and writers must go to the people .—,not descending, but ascending to them. . . in the people is to be found the source of future works, the daily inspiration and the supreme inspiration.. And to the people the literary or artistic products must finally return: a return of the treasures which the people give in the artists every day."

On the morning of August 19th, poet Nicolas Guillén took a journey

through Cuban history, from which he returned asking the artists and

writers to create a "socialist, humanist culture that will give the

ordinary man in the street everything that was denied him by the

Colony in the 19th century and monopolized by an exclusive sector of

the ruling class of that society... a culture that will liberate and

exalt us and distribute both bread and roses without shame or fear".

The publication in this book of Fidel's words to the intellectuals

and the speeches by Dorticós and Guillen will enable English-speaking friends of Cuba throughout the world to form a clear idea of the spirit with which the Revolution is tackling the problem off culture.

Without exception, the only condition that of being unequivocally on

the side of the people, the Cuban Revolution protects the rights of

creators, of scientists, of intellectuals. Even more, it stimulates

their work and opens new horizons to them. With a better world in

view, writers and artists, side by side with the people of whom they

are a part, are helping to build the society of the future

FULL RE-FORMATTED VERSION OF FIDEL'S SPEECH:

http://www.walterlippmann.com/fc-06-30-1960.html

No comments:

Post a Comment