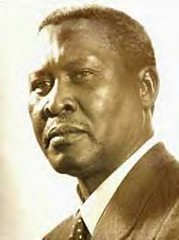

Chief Albert J. Luthuli, former president of the African National Congress and a winner of the Nobel Peace Prize. The fortieth anniversary of his death in 1967 took place on July 21.

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire File Photos

The Wankie and Sipolilo campaigns of 1967-8 had a significant impact internationally and within the country, demonstrating to the people of South Africa that the ANC's armed struggle was very much alive, writes Sandile Sijake.

When the ANC and the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) agreed on close cooperation in relation to guerrilla operations, it was understood that the activity was taking the existing solidarity a step further. The relationship between the peoples of South Africa and those of Zimbabwe had from then onwards to be tempered in the fires of the common experiences in the struggle for social, economic, political and cultural emancipation.

In the ANC there had been a long period of unplanned attempts at infiltration of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) members back to South Africa. These attempts were mainly focused on finding a route through Botswana. To facilitate the crossing we established a bone milling facility in one of the farms outside Livingstone. The facility worked very well for some time.

However the process of infiltration involved very small groups of one or two at a time. The rate of arrests and interception by the Botswana Paramilitary Police led some of us to suspect that there was a serious leak of information. The second concern was that whatever weapons the cadres carried along ended up in Botswana and there was no way that these could be recovered.

A number of frank discussions were held, mainly with then ANC President OR Tambo. In his absence these meetings would be chaired by Moses Kotane. Moses Mabhida and JB Marks were charged with finding routes other than Botswana. They set up a number of networks that became promising, and were operational.

There was an apparent tendency that some individual leaders placed more emphasise on commercial interests than the struggle for social, economic and political emancipation. These interests manifested themselves in the fact that these leaders set up factories and operated commercial farms mainly in Zambia. Bitter arguments also related to the fact that cadres sent to South Africa were given a mere five pounds to see them through operations, food, transportation and accommodation, to give but a few requirements of any political-military operation.

Members of MK appealed to the leadership that they be part of the planning of routes home. The joint operations with ZAPU's armed wing, the Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA), evolved out of this process. We agreed to have a combined venture with the specific understanding that we were to be on our way to South Africa. This took place after MK tried to have similar arrangements with FRELIMO in 1966. This could have been feasible given that at that stage FRELIMO was still operating up to Tete Province north of the Zambezi River.

The operations

Once the political strategic levels accepted the rationale of undertaking a form of combined operations, a number of corresponding structures had to be put in place to ensure implementation of the agreement. A joint intelligence-cum-reconnaissance structure was established with Eric Manzi (MK) and Dumiso Dabengwa (ZIPRA) as respective leaders. There was also set up a Joint Headquarters (JHQ) consisting of the Overall Commanders, Commissars, Chiefs of Staff, Chiefs of Operations, Chiefs of Logistics and Supplies and a limited involvement of medical officers.

Each of these components of the JHQ had its particular teething problems, some of which it was possible to address, others were to be placed in abeyance, while some had to be wished away. In reconnaissance these challenges led to a form of ad hoc and autonomous activity. All the moves and steps taken were to be balanced to ensure all parties were happy with the process. When the structure of the detachment was assembled each level of authority had to be given serious consideration. It was finally agreed that John Dube of ZIPRA be the detachment commander and Chris Hani the detachment commissar.

In August 1967 a combined force of MK and ZIPRA freedom fighters were seen off across the Zambezi River by Tambo. The force numbered about 96 men with no maps, and limited dependence on ZIPRA cadres who, although Zimbabweans, had no better clue about that part of their country. The detachment had to rely on compasses for a general direction of march.

When this detachment was to cross into then Rhodesia there were two clear directives. The ZIPRA comrades were to establish themselves in their country as a guerrilla force. The ANC cadres were to head to South Africa and without any particular intention that they should engage the enemy inside Rhodesia except when necessary and as means of self-defence.

Inside Rhodesia the detachment was going to split into two main groups and a third part was going to be a group of two cadres using a train. One company was to head east towards the Matopo Hills, Paul Petersen and two other comrades were to go to the nearest railway station and take a train towards the midlands, and the main body was to move on the western part heading south.

The MK contingent intended to use Rhodesia as a passage home and not to conduct any operations in that country. No one among us knew that the first clashes with the enemy would take place in the vicinity of Wankie.

The members of this first detachment had to learn on their feet as they could not avoid blunders associated with undertaking such an operation without sufficient means and equipment. The situation was tense. On crossing the Zambezi river the detachment set up its own reconnaissance section. Some of the functions of reconnaissance were to move forward and backwards finding the routes to follow, water points, food, and information on the activities of the enemy.

The going was never smooth. On certain occasions arguments would be sparked by the issue of who must lead the detachment to the point identified by reconnaissance. Most times the ZIPRA cadres in reconnaissance would insist that they wanted to lead. Every time one of them had been given the opportunity to lead, the detachment would end up going astray and never linking up with that small contingent of reconnaissance left ahead to secure a new temporary base.

On the second day inside Rhodesia, the detachment ran out of food, bullets were in short supply and most, if not all, the MK members had about five pounds and not much water. There was no information about the quantities of rations each was going to get until they were on the banks of the Zambezi River and ready to cross.

The detachment reached the first village on the second day. The small community there gave valuable information to the guerrillas. They indicated that the previous day some soldiers came to their village and said they were looking for guerrillas. They could not remember the number of trucks or soldiers. The leader in that community was a ZAPU supporter and told the detachment that the soldiers did patrols during the day and at night; and their camp was on the other side of the next village. This man was willing to go to a shop owner at the next village and arrange for the purchase of food. The community gave some food to the reconnaissance group for the rest of the detachment.

The reconnaissance group discovered that the shop owner at the second village was also a ZAPU supporter. He gave valuable information about the enemy activities. He told them that all the passable routes converged near the soldiers' camp. After leaving his place the reconnaissance group established that there was a small enemy contingent at that camp. They were seated next to a fire and now and then one of them would go and look along the road intersection and return to the fire. The detachment decided to walk past the camp as they believed they would easily overwhelm the enemy. On seeing the detachment the soldiers ran away, abandoning the camp.

The detachment marched the whole night before deciding to have a long rest. After some rest we noticed that one member from Charlie Company was missing. We searched for him and after about two hours the search was called off and the detachment moved on.

On about day six, the detachment ran out of the food they had bought from the village shop. However, they arrived at a game reserve on the Shashi River valley where they shot a zebra for a meal and provisions. They had some water after having dug in the sand for about one and half metres.

Company B was now to move east in the general direction of Matopo Hills. Their immediate task was to see Paul Petersen to a train station at Dede. They parted with the rest of the detachment that now numbered about eighty guerrillas, heading in the general direction of Wankie.

Early the following day, radio news reports on some battles involving Company B started to filter through to the rest of the detachment. It was reported that one of the battles took more than six hours until the comrades ran out of ammunition. Some were arrested and many died there. Putting the pieces of information together, it appears that when Company B were at Dede station one of them was seen drinking water at a public tap. The enemy got an alert signal and the upshot was that the company was followed until the point of battle.

Similarly, Paul Petersen was followed as he travelled by train. He travelled over Tsholotsho area towards Plumtree. He apparently realised that he was being followed and got off the train, using a sub-machine gun he cleared the first road block he encountered. From that roadblock he took a motorbike and carried on southwards towards Plumtree. Riding on along the road, he found himself at an even bigger roadblock than the previous one. He opened fire, fighting his way and finally fell there.

On hearing the news of the fighting, the main body of the detachment decided to keep our radio sets on continuously, listening to the news. We moved more in the open with an aim of attracting the enemy, in the hope that they would not concentrate on Company B alone.

In the early morning of the ninth day while comrades Wilie, Modulo and Christopher Mampuru were conducting reconnaissance they spotted a large herd of animals. They followed the animals at a distance of about 200m. This led them to a big pond ahead. They were now cautious and had to consult with the rest of the detachment before shooting any of the animals. Wilie left Modulo and Christopher who decided to remain watching the animals while he went back to consult. They were not going to meet again.

Before Wilie could give any report to the detachment two spotter planes began circling the area of the pond. The detachment took up positions in battle formation as the enemy patrols in the air intensified and ground forces appeared in trucks from the direction we came. The enemy trucks passed the positions of the main body and headed for the direction of the pond. After a few moments gun fire sounded in that direction, apparently Christopher and Modulo engaged the enemy.

The following day, while the detachment was having a rest, it was hurled into action by the sound of an exploding hand grenade. The grenade exploded at the position occupied by members of a section consisting of comrades Berry, Baloi, Manchecker, Sparks and Mhlongo. Baloi and Berry died on the spot. Sparks got a bullet through the abdomen and Mhlongo was critically wounded. The enemy was busy shouting: "surrender there is nothing you are going to do".

The detachment engaged the enemy. Their remnants fled from the battlefield leaving behind their dead, maps, supplies and radios. There was one casualty on our side, Charles Sishuba. The members of the detachment got food supplies, fresh clothing, watches and water bottles and used the radios to mislead the enemy. From the maps members of the detachment were able to know about the plans of the enemy and routes they were using.

The disinformation attempts by the detachment proved to be effective, as the enemy acted on the information they received. They ended up one evening shooting at each other near a water pond. After that incident they changed their radio wave band.

The detachment reached the area of Manzamnyama, and they had a brief encounter with some members of the Rhodesian Rifles, who were predominantly black soldiers. After Manzamnyama the detachment was supposed to veer away from the Wankie Game Reserve. The terrain in the intended direction was sparse and any movement would be easily detected. The enemy was still pursuing the detachment.

During the day, while the detachment rested, the silence was broken by the sound of Halifax bombers pounding the bush area about a kilometre away from the isolated trees where the detachment rested. The bombings started a yellowish fire, characteristic of napalm bombs. After the bombers, the ground forces arrived in their trucks and started to conduct a mop-up operation.

Late the following evening the detachment fought its last major battle with a combined force of South African and Rhodesian soldiers. The enemy was routed and the detachment's casualties include comrades Donda and Jackson Simelane.

The detachment proceeded in the general direction of Plumtree. As they moved they did not realise they had strayed into Botswana. They were arrested by Botswana paramilitary police in small groups as they came across them.

The arrest of the last group more or less ended the Wankie part of the campaign and triggered the Sipolilo phase.

Sipolilo

The JHQ undertook a general review of the Wankie battles and as the news reached Lusaka through Rhodesian citizens working in Zambia and other numerous sources, the main talk in both the ANC and ZAPU circles was that of sending reinforcements. This remained in the heads of the members of the JHQ after the fighting had died out and all survivors had been arrested. The second phase was to follow a different belief and thinking.

The plan for the second phase was based on the assumption that it was important to have a sustainable base inside Rhodesia before starting operations in South Africa.

The second detachment crossed to Sipolilo between October 1967 and January 1968. At the end of December 1967 there were over 150 guerrillas in the bushes of the eastern part of Rhodesia. The number fluctuated as more people joined and a few returned to Zambia.

The second detachment was instructed to establish guerrilla bases inside Rhodesia. They were to identify a place to set up an internal headquarters with all the necessary components, as well as alternative bases in case of need. Timeous communications with Morogoro and Lusaka (linking to ANC HQ) was going to be maintained by means of a long range multi-functional radio acquired from Germany. The radio was to be powered by means of a generator. The fuel for the generator was to be acquired from Zambia and stores were to be established by the detachment itself.

The detachment was expected to establish a number of arms caches, assisted by a supply group assembled for the purpose. The weapons, rations and uniform replenishment were supplied from Lusaka. Some of the reasons behind supplying the detachment with food and clothing was to ensure that they did not get involved in extensive hunting as that would attract the enemy.

The JHQ in Lusaka left all the main decisions to the command structure of the detachment. Teams visited the front from Lusaka and Tanzania, taking photographs to show that we had a presence behind the enemy lines. At the same time enemy activities started to grow in the general vicinity of the game reserve.

Early one morning in April 1968 the main bases that had been established in the area were the target of intensive bombing. The enemy ground forces followed the bombing. The enemy had learnt from the previous operations the importance of combining air and ground firepower. This attack triggered the clashes that were to last for more than a week, as pockets of the detachment fought in different directions, with the main force fighting towards Salisbury.

A number of comrades died in the battles that ensued, some were arrested and a few ended up in South Africa. There were then two routes to South Africa; some comrades found their way home and finally got arrested, while others were brought home through an agreement between Rhodesian and South African officials.

April 1968 was the climax of what has come to be known as the Wankie campaigns. The significance of these campaigns internationally is that they led to countries like the USA reshaping their policies on Southern Africa. Internally, the South African regime formulated the notorious Terrorism Act. The masses of our people became aware that the ANC was very much alive and still the main political vehicle for social, economic, political and cultural emancipation.

SANDILE SIJAKE was a member of the Luthuli Detachment of Umkhonto we Sizwe.

2 comments:

This is very informative we have been denied access to such information very few young people in present day Zimbabwe know about the close links between ZAPU and ANC. Its hard to get hold of such intresting information if you are a young Ndebele. If there is more literature on the operations of ZIPRA and ANC please please send me some my email is qhoshi03@yahoo.co.uk

ZAPU and ANC will always be brothers and sisters...the shared struggle says it all...Long live ZAPU.

Post a Comment