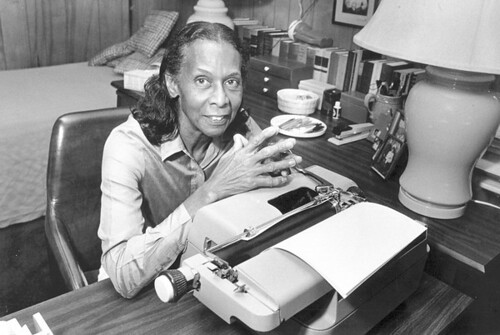

Almena Lomax was a pioneer in the field of journalism. As an African American woman she rose to the top of her profession during the 20th century., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

OBITUARIES : ALMENA LOMAX, 1915 - 2011

She founded the Los Angeles Tribune in 1941 and was its editor for 2 decades

April 01, 2011

Elaine Woo

Almena Lomax, a journalist and civil rights activist who launched the Los Angeles Tribune, a feisty weekly newspaper that served the African American community in the 1940s and '50s, died March 25 in Pasadena. She was 95.

Her death came after a short illness, said her son, Michael, president and chief executive of United Negro College Fund.

Lomax, whose daughter, Melanie, was a prominent attorney and former president of the Los Angeles city Police Commission, was a leading figure in African American journalism, known for her sharp opinions and independent spirit. She founded the Tribune in 1941 and was its editor and chief writer for two decades, achieving a circulation of 25,000 with a lively mix of news, commentary and reviews.

The paper often bore the traces of what poet-playwright Langston Hughes, an avid Tribune reader, described as "impish" humor. One of his favorite examples of the playful tone set by Lomax was a Mother's Day headline that read, "The Hand That Rocks the Cradle Has Got the World All Loused Up."

But Lomax also had a reputation as a hard-hitting journalist willing to stir controversy with stories on such topics as racial discrimination in Hollywood and police mistreatment of blacks.

"She was a terrific writer ... the only one of all the black newspapers at the time who really was fearless about exposing things as they were. She didn't soft-pedal anything," said veteran civil rights lawyer Leo Branton Jr.

As the civil rights movement gained momentum in the early 1960s, Lomax uprooted her children from Los Angeles to live in the Deep South. The move bewildered her friends, including Tom Bradley, the future Los Angeles mayor. But Lomax, who described herself as "a 20th century frontierswoman," was determined not to miss what she regarded as the defining event of her generation.

"Negroes who lead, or can lead, who have any motivation at all toward bettering the world for mankind, need to go often into the teeth of Jim Crow and know it for its brutal, dehumanizing reality," she wrote in "Journey to the Beginning," an account of her family's experiences with segregation, published in 1961 in the Nation magazine.

After her sojourn in the South, she became a copy editor at the San Francisco Chronicle and a reporter at the San Francisco Examiner, where she covered the kidnapping of Patty Hearst and the hunt for black revolutionary Angela Davis. Her work also appeared in Harpers and Ebony.

Lomax was born Hallie Almena Davis on July 23, 1915, in Galveston, Texas. The second of three children of a seamstress and a postal worker, she spent her early childhood in Chicago before moving with her family to Los Angeles. After graduating from South L.A.'s Jordan High School, she studied journalism at Los Angeles City College.

In 1938, unable to find a job at a major daily newspaper, she accepted a position at the California Eagle, a black weekly founded in 1879 by an escaped slave. After two years, she left to host a local radio news show, returning to print journalism in 1941 when she started the Tribune with a $100 loan from her future husband's father, Lucius W. Lomax Sr., a gambler and businessman who owned the legendary Dunbar Hotel on Los Angeles' Central Avenue. Lomax Jr. joined the paper as publisher in 1943 and married the editor six years later.

Lomax quickly earned distinction for her newspaper. In 1946 she won the Wendell L. Willkie Award for Negro Journalism with a provocative story challenging the stereotype of black men's sexual prowess. She was an early advocate of multiculturalism, hiring two Japanese American writers who had been interned during World War II: Hisaye Yamamoto and Wakako Yamauchi, who went on to distinguished careers as a short-story writer and playwright, respectively.

In 1956 Lomax left her husband and six children for a week to cover the bus boycott in Montgomery, Ala., where she met its leader, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Tribune subscribers subsidized her trip, but her husband disapproved and the marriage began to crumble.

The couple divorced in 1959. The following year she closed the Tribune and left for Tuskegee, Ala., with her children -- who ranged in age from 4 to 16 -- in an old Lincoln that broke down outside Blythe, Calif. They made the rest of the journey by Greyhound bus.

Their first encounter with segregation came at the bus station in Big Springs, Texas. Lomax refused to take her hungry brood into the lunchroom reserved for blacks. Instead, she marched them into the whites-only dining room. "I don't intend to be Jim Crowed," she told the manager. She was denied service but stood her ground, even when four police officers arrived.

No harm came to Lomax and her family, but the firsthand experiences with brute racism "traumatized the six of us," son Michael said of his brothers and sisters.

"It was one of the regrets she carried her entire life," he said of the impact of his mother's decision to take them into the trenches of the civil rights movement. "On the other hand, it was the story of her lifetime, and she tried very hard to tell it."

Lomax was preceded in death by two daughters, Melanie and Michele. In addition to her son Michael, of Washington, D.C., she is survived by three other children: Mia and Mark, both of Los Angeles, and Lucius of Austin, Texas; four grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren.

elaine.woo@latimes.com

No comments:

Post a Comment