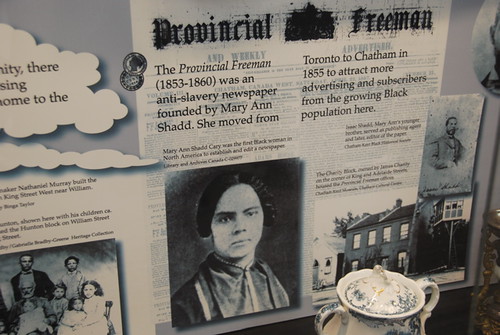

19th Century abolitionist Mary Ann Shadd who founded the Provincial Freeman newspaper in Toronto, Canada in 1853. She relocated the publication to Chatham in 1855 to enhance sales and advertising., a photo by Pan-African News Wire File Photos on Flickr.

Emancipation Proclamation and Night Watch

By Dolores Cox on January 2, 2013

Workers World

Jan. 1, 2013, is the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation by U.S. President Abraham Lincoln. Effective Jan. 1, 1863, during the Civil War, the document declared that enslaved people of African descent in all states rebelling against the Union would be “forever free.” In commemoration of this anniversary, the U.S. Postal Service will be issuing a stamp.

Months earlier, Lincoln announced that if Confederate states did not cease fighting and rejoin the Union by Jan. 1, all enslaved people in those states or areas would be declared free from that day forward.

The Proclamation gave hope to those enslaved, who gathered the night of Dec. 31, 1862, in their churches waiting up to midnight for word of their freedom, by word of mouth, telegraph or newspaper.

The Proclamation did not itself immediately free the four million enslaved people nor could it be enforced in areas under control of the secessionist Confederacy, which ignored it. And it didn’t apply to slave-holding states that hadn’t rebelled against the Union. But it paved the way for the abolition of slavery under the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution ratified on Dec. 6, 1865. The 15th Amendment, passed during Reconstruction on Feb. 3, 1870, supposedly gave all male U.S. citizens the right to vote regardless of race, color or past servitude. This amendment did not apply to any African Americans, male or female, in the South until 1965 when the Voting Rights Act was enacted through mass struggle.

Freedom delayed

In Galveston, Texas, freedom didn’t come until 1865. News of the emancipation was suppressed due to the overwhelming influence of slave owners. June 19th is considered the effective date when the last enslaved people discovered slavery had ended.

The date is known as “Juneteenth” and is recognized and celebrated as the “Fourth of July” for many Black people in the U.S.

When the United States gained its independence from the British, Black people were still enslaved. In 1963, a hundred years after the Emancipation Proclamation, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom took place. It attracted 250,000 people.

The tradition of “Watch Night” is deeply rooted in the history of African Americans, especially at a time when the community is still struggling. New Year’s Eve church services in Black churches still celebrate the day before the Proclamation became law. The five-page document may be read aloud at these services. And possibly a sermon may address the progressive and sometimes regressive moves that Black people have struggled and continue to struggle through.

Enslaved people inside the U.S. lived under one of the most inhumane experiences in human history. And the wealth created by more than 200 years of their free labor has benefited mainly the 1% — the ruling class — and least of all, African Americans themselves. The legacy of slavery still divides those who live inside the U.S. — a morally corrupt country that thrives on policies that help reinforce racist attitudes of Black people as being inferior, even subhuman.

Racism continues to be tolerated, insidious and pervasive. Every day in the U.S., African Americans are reminded of their slavery legacy. Therefore, social justice is still being fought for daily.

No comments:

Post a Comment